Dinner at the Pompeii takeaway: The empire's feasting was legendary, but what did ordinary Romans eat?

Alasdair Riley takes a bite of the past

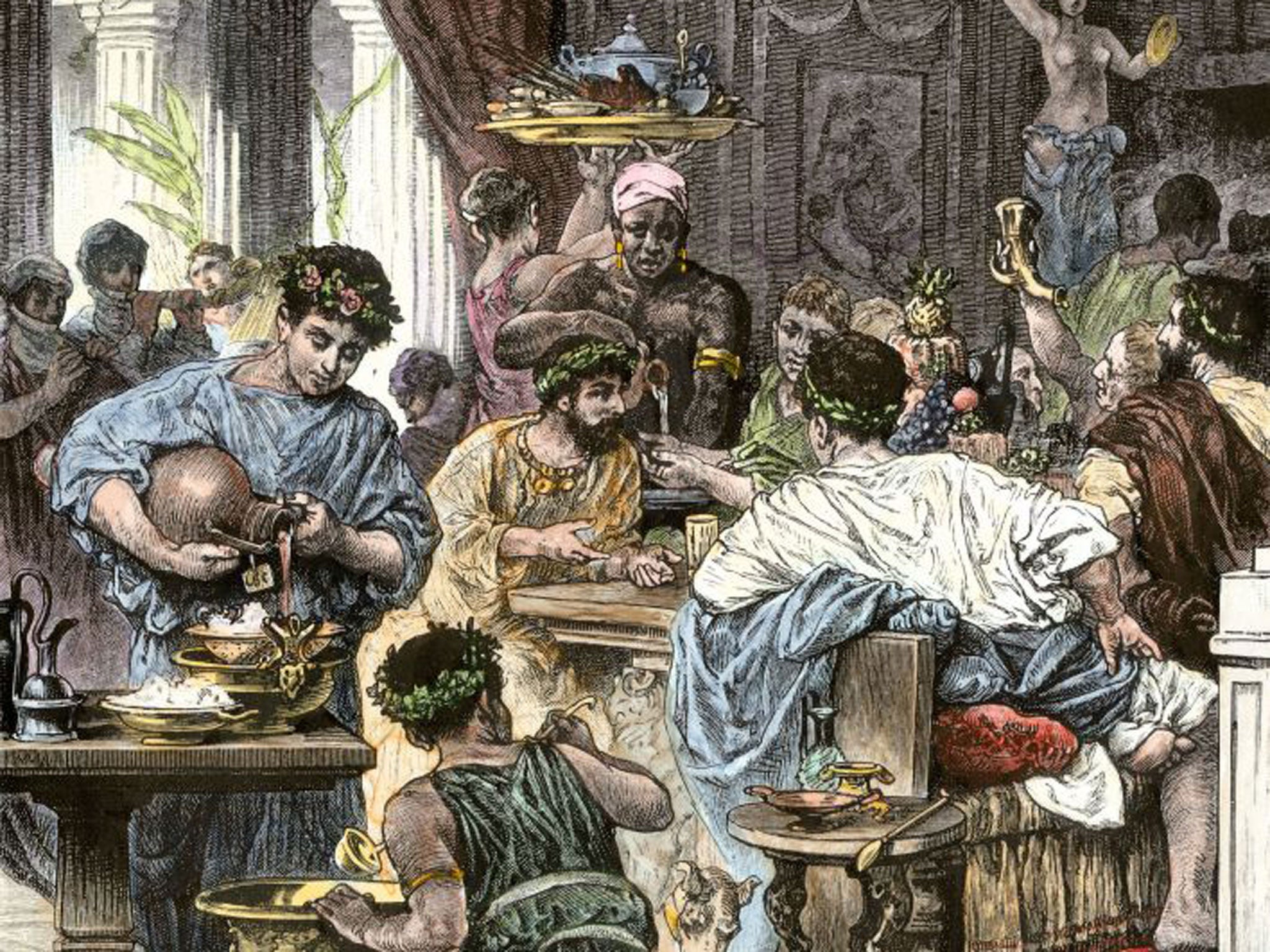

Whatever your Classics teacher said to wake up slackers at the back of the class, the Roman diet in ancient times was not always a blow-out of tender larks' tongues and roasted flamingo followed by a medicinal visit to the vomitorium.

Standard fare came from whatever was available in the larder or by handing over a few sestertii coins at their equivalent of our local chippy or burger bar.

"Baked dormice and roast parrot were occasionally found on the menu," says Mark Grant, who has spent a lifetime researching the everyday food of the Roman Empire. "But only a few wealthy and bored Romans indulged in such excesses, and even then only on high days and holidays.

"This gave moralists and satirists something to moan about. It was headline stuff which they wrote about at great length. Reading these accounts today is a bit like eating a TV snack while watching Heston Blumenthal on the telly, concocting something extraordinary out of jellyfish that we'd never dream of cooking at home."

That's one of the reasons why Life and Death: Pompeii and Herculaneum, the sell-out exhibition at the British Museum, is so absorbing. It's a snapshot in time, when Mount Vesuvius erupted AD79. Clouds of ash poured down from the sky, engulfing thousands of citizens in a tremendous blast of heat, fixing them at the moment of death.

Grant, 52, author of Roman Cookery: Ancient Recipes for Modern Kitchens, says: "The gold bracelet in the form of a coiled snake or the marble sculpture of the god Pan having sex with a she-goat are show-stoppers. But I go straight to the culina, or kitchen, with its equipment such as a colander or the pottery bottle for fish sauce. There are frescos showing a panel of fish, or a loaf of bread and two figs.

There are paintings of everyday food: a rabbit grazing on a bunch of grapes and two partridges hanging on a wall. The food is so real you can almost smell it and eat it. "The home and domestic life are things we all share. The exhibition is a wonderful opportunity to explore how people like us lived in Roman times. They didn't all go to the baths or the amphitheatre but everyone, poor or wealthy, had a home."

As a 16-year-old schoolboy in Bristol, Grant discovered ancient Roman cookery was his hobby. He was the most popular boy in his class when he appeared on Mondays with a satchel full of home-baked bread and sausages made from hog casings acquired from his local butcher, filled with ground pork flavoured with spices from the city-centre market.

His hobby became a passion at the University of St Andrews, where he studied Classics. He was feted for the meals he cooked for the university Classics society (togas encouraged, but not mandatory). Other feasts followed there while researching his doctorate on the diet of Roman emperor Julian the Apostate.

Now firmly launched on a voyage to the wilder shores of food culture in the ancient world and with a taste for exploring uncharted territories on the Roman gastronomic map, his collection – and translation – of recipes grew and grew. As well as seeking out hidden gems among the pages of less well-known works, Grant had a nose for the aromas of the kitchen and became a dab hand at the stove

His academic studies and his hobby took a practical turn when he then enrolled as a student of catering management at Manchester Polytechnic. The one-year course included a compulsory chef's traineeship during which he developed professional skills that allowed him to adapt ancient Roman recipes for use in the modern kitchen.

Grant is now a careers adviser on the staff of the International School of Geneva, Switzerland. Invited to dinner at his home, you may be offered a dish fit for an emperor, such as luxurious cake made from nuts, honey and dried figs. Or something from the pleb end of the class spectrum, such as butter beans in herb sauce, appropriately, all washed down with Lacryma Christi, the Neapolitan wine from vineyards on the slopes of Mount Vesuvius.

Or guests may be treated to the kind of food – fried fish, ham or sausages – served to a clientele of drunks, thieves, prostitutes and lazy slaves in popinae, the fast-food outlets in Roman Empire times.

Although Roman Cookery is a book based on serious research, Grant treats his subject with a light and accessible touch. He divides his recipes into breakfast (porridge, mainly), lunch (a light meal – bread, cheese, olives and fruit – essential to maintain energy for the working day) and dinner at home (a more complex affair, perhaps with a beef casserole or fish in vine leaves as its centrepiece).

There is also an excursion into the recipes of Roman taverns, which, as well as serving food and drink, sometimes doubled as brothel or gambling den. Clients could pay with coins that they carried in their mouths, rather than purses, and then spat out when it was time to settle up. Grant puts his money where his mouth is, spending his teacher's pay not just on decent olive oil, figs and citron lemons or whatever is in season at the greengrocer, but also on humbler ingredients such as barley and chickpeas. Whether in Switzerland or the UK, he does as Romans do.

More exactly, as Romans did. And then he adapts for today's kitchen. He says: "There is a direct link between cooking during the Roman Empire period 2,000 years ago and modern European cooking, especially the Mediterranean diet with its emphasis on olive oil, fish and fresh vegetables.

"This week, I made a herb purée with pine kernels and spread it over lagana, a kind of fried pasta that Romans used to scoop up whatever they were being served with. When it is my daughter's birthday, I might make cheese-bread as a special treat. It is made with grated cheese, an egg and wholemeal flour, kneaded into dough and flattened into small lumps before baking them in the oven. In Roman times, this was served as a birthday cake or presented as a humble offering to the gods."

'Roman Cookery: Ancient Recipes for Modern Kitchens' by Mark Grant (Serif, £10) .

'Life and Death in Pompeii and Herculaneum' is at the British Museum until 29 September

Herb Purée with Pine Kernels

Serves 6

The origin of modern Italian pesto, but without basil, which was rarely used by Roman cooks. Superstition had it that it attracted scorpions.

100g pine kernels or hazelnuts

80ml olive oil

80ml red wine vinegar

Half a teaspoon ground black pepper

125g feta cheese

2 or 3 mint leaves

Handful of fresh coriander leaves

Handful of fresh parsley

Sprig each of savory, rue and thyme

Sea salt

Put all ingredients into food processor. Purée until smooth. Serve with bread. If using hazelnuts, roast under grill for 5 minutes to release their nuttiness, turning frequently to avoid burning.

Lagana, or Fried Pasta

Pasta dough was not cooked directly in water or soup until the Middle Ages. Here it is fried. Serve to accompany soup or casseroles in true Roman fashion, or in modern style as a tasty garnish. For example, with herb purée. Makes approx 30 small biscuits.

120g wholemeal flour

100ml water

Olive oil for frying

Measure flour into a bowl and add water. Knead into a stiff dough, adding a touch more flour of water if necessary, and form into a ball.

Flour a board and roll the ball out, turning the dough frequently to avoid sticking.

When it is almost paper thin, cut into pieces about 2.5cm wide and 3cm long. Heat olive oil in a pan and add the dough. Fry so that both sides are golden and crisp.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks