An Italian dish invented in Mexico and all the other ways you’re getting Caesar salad wrong

It’s the classic dish that is sold across the world everywhere from high-end restaurants to cut-price supermarkets, but as it turns 100 years old this month, Josh Barrie delves into into its forgotten history and finds controversy and dispute at every turn

The Caesar salad is one of the world’s most cherished dishes, today sold everywhere from hotels in Bangkok to pubs in Australia, cafes in Argentina to restaurant chains in Britain. Who hasn’t panic-bought Pizza Express’ version of the salad dressing for a last-minute summer barbecue?

But while many will be forgiven for having assumed the world’s most famous salad is some ancient Italian invention, traced back to a Roman trattoria like carbonara, the salad, which is one hundred years old this month, has a history as rich as its umami-laden sauce.

In part, we do have Italy to thank: the caesar salad is the work of an Italian immigrant, the hotelier Césare Cardini, who first crafted it in Tijuana, Mexico, in 1924. Like many dishes, he did so only because he found himself with a sparsity of ingredients and innumerable people to entertain. One-hundred years later, those ingredients are still disputed today.

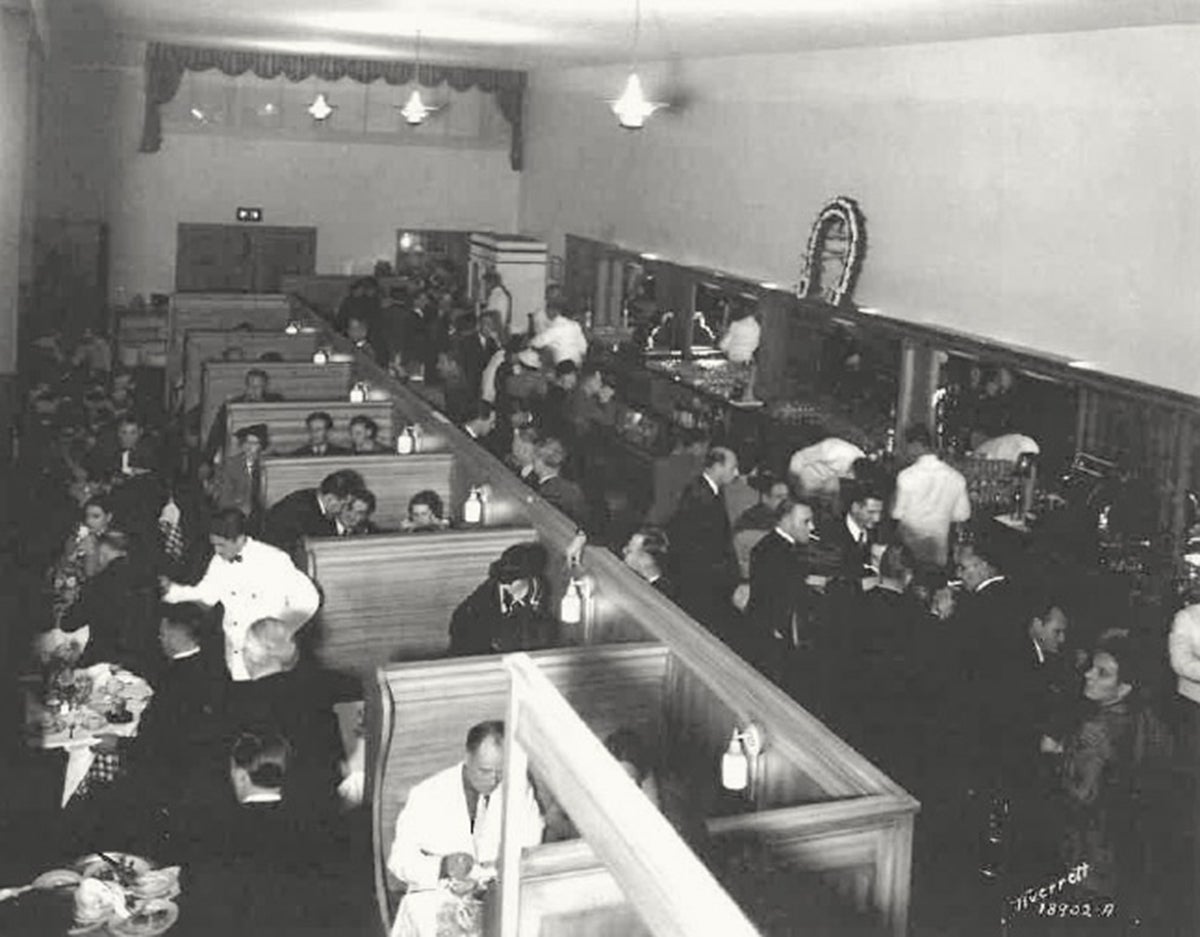

Cardini and his brother Alex had moved to the Mexican border town to open a hotel and restaurant, itself called Caesar’s. It soon became popular with wealthy Americans – many of them celebrities – who fancied a drink during prohibition but didn’t want to travel far.

Chefs made use of ingredients they could always get hold of and provided theatre for waiting customers: salads were made tableside for all to see. Ideal when waiting for steaks and while sipping martinis.

Like any classic dish, not least one with Italian heritage, the origin story is disputed. Ask Aldo Santini, the grandson of one of Cardini’s cooks, Livio, and he’ll tell you that the recipe was invented by his grandfather’s mother back in Italy and he made it for himself whenever he was homesick.

He told The New York Times Cardini saw it, tried it, and put it on the menu the next day. Cardini’s brother Alex went on to more rambunctiously claim to have a bigger hand in its creation in the years that followed, further complicating matters.

Whatever the origins, in 1933, booze-cruise tourism having waned and the salad already famous, Cardini sold up and moved to Los Angeles, where he started a grocery store and a bottle version of the dressing – Cardini’s Original Caesar Dressing – still sold in supermarkets today.

Naturally, the caesar salad has been tweaked and altered by chefs over time. What is often credited as the original recipe – there were no anchovies in the first experiment, though they were added soon after and are now considered indispensable – is preserved by Cardini’s brother’s grandson, also called Alex, who recently appeared on US television to prepare it.

“There are two types of caesar salad: the Cardini one, and the others,” Alex told CNN. The former includes a one-minute boiled egg, garlic olive oil, anchovies, parmesan, Worcestershire sauce, dijon mustard, lemon juice, vinegar and croutons, all added to sheets of springy romaine lettuce, leaves left whole.

Visit Caesar’s today and you will taste limes over lemons: the current chef, Tijuana-born Javier Plascencia, putting his own stamp on the dish (the restaurant has closed and opened under various owners over the decades, its glory days long since past). Why limes? Because they are more readily available in Mexico. Otherwise, the glamorous, careful tableside salad has returned. Even in quieter periods, Caesar’s reportedly serves about 2,500 salads a month.

Elsewhere, particularly in the US and Britain, it is as popular as ever, relied on as a familiar but adventurous enough menu item. It’s clean but indulgent, a light but satisfying blend of fat and freshness.

Will Beckett, co-founder of the international steakhouse Hawksmoor, has just opened another site in Chicago, and expects the Caesar to perform there as it does among his other branches. He tells me Hawksmoor sells about 250,000 caesar salads a year.

“It is salad royalty,” he says. “It’s an institution. In Europe, it might be the bridge to Americanised salads. Here, a salad is mostly vegetables in a light dressing. In the States, it’s wedges and blue cheese – moves to indulgence. It’s what men who eat lots of meat want next to their steak alongside creamed spinach. Helps move the whole thing along.”

Beckett also says that caesar salads take on a variety of forms. “There’s a set format to it, but everyone feels they can be a bit playful. Each one is a little bit different, even if ours is fairly classic.”

Cardini, the great-nephew of the credited inventor, roundly denounced the inclusion of bacon and tomato. Chefs have gone much further than that, adding everything from fried chicken to tandoori prawns and every meat in between. Dressings, meanwhile, are strewn with seeds or lightened with yoghurt; salad leaves are changed and herbs, capers, broccoli added to aid a greater perception of nutrition. And there have been varieties with kimchi, orange zest, togarashi, miso. Eggs could be from any bird.

So when does a caesar salad stops being the sum of its parts and becomes a new dish entirely? It is likely that Caldini, an Italian, would bemoan its meddling. But he would almost certainly be happy to see it flourish.

Owen Kenworthy, who has helped breathe new life into another institution, the West London restaurant Julie’s, serves his caesar salad with lobster, adding stock into the dressing and the meat to the bulk of the dish.

He says: “Growing up in Blackpool, it was one of those classic dishes. And I loved it from the beginning – a simple salad of lettuce and dressing, but one that feels luxurious and special. The dressing is so well balanced and, when done properly, thick, so it can be a good starter or side, or a light lunch.”

Might a caesar salad be a dish that’s easy to do, but hard to do well? “You need to get the saltiness right, but you need that acidity. I’ve worked off an old recipe for years and worked on it as I’ve gone along. I add lobster meat at Julie’s, and I breadcrumb the claw.

“A word must also be said for croutons. A lot of people f*** them up. They’re a moreish, delicate thing; they can’t just be a dry afterthought.” At Julie’s, diners will find yesterday’s sourdough, cut into half-inch cubes, and plunged into clarified butter before being baked at 170C degrees for seven minutes.

It is these details that have helped propel caesar salad to global stardom: made by immigrants, often for travellers, using ingredients that were particular 100 years ago and specific today. Worcestershire sauce, first made by an English chemist in the 1800s, is now referred to as “salsa inglesa” by some.

I have not yet made it to Caesar’s in Tijuana. The closest I have come is the version made at the Golden Steer Steakhouse in Las Vegas. It is a credible iteration – Beckett namechecks it, too – made tableside by skilled waiting staff in waistcoats and polished shoes. The seasoning there is expert.

And it ought to be. The caesar salad is a century-old phenomenon. And though it has nothing to do with the Roman emperor with whom it shares a name, it has been just as deliberate in taking over the world.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks