I learned how to make Vietnamese food from scratch at home – now I’m hooked

Sour, spicy, sweet, bitter and salty, Vietnamese food has the power to hit all your taste buds. Ella Walker finds out how to make it at home

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The first pancake is always a dud. It doesn’t matter how smooth your batter, how hot and Teflonned your pan; the debut is always a crumpled mess that flops sadly onto the plate.

This is true whether it’s an English pancake destined for lemon or sugar, or, as in this case, a turmeric-spiked rice flour and coconut milk crepe, laden with plump prawns and a forest floor’s worth of coriander. Impaled by rogue beansprouts and soggy rather than crisp, I have utterly massacred food writer Uyen Luu’s sizzling crepes. I hope she will forgive me.

I order in Vietnamese food every chance I get: fragrant chicken pho (”fuh”); coarsely shredded papaya salads; golden spring rolls and enticingly translucent summer ones; pork-prawn wontons with sesame and chilli oil; chargrilled, fish sauce-drenched aubergines… but until now, I’d never attempted to cook it myself.

Why even try when the depth of flavour seems unfathomable to achieve? When every dish is so zingy and bold, fresh and sprightly? Who has such lightness of touch? Luu, that’s who. And me, it turns out, when armed with Luu’s new recipe collection, Vietnamese.

The dishes in the brilliantly blush pink cookbook are designed to “demystify Vietnamese cooking”, promises Luu, who reckons the most common mistake people make when approaching the cuisine, is “they think it’s more complicated than it is”.

You can’t really blame them (OK, me) when the “flavours feel and taste complex”. However, to hit those key Vietnamese flavours – sweet, sour, salty, umami, hot and bitter – it’s just a matter of combining ingredients, Luu insists. There’s no need to be intimidated.

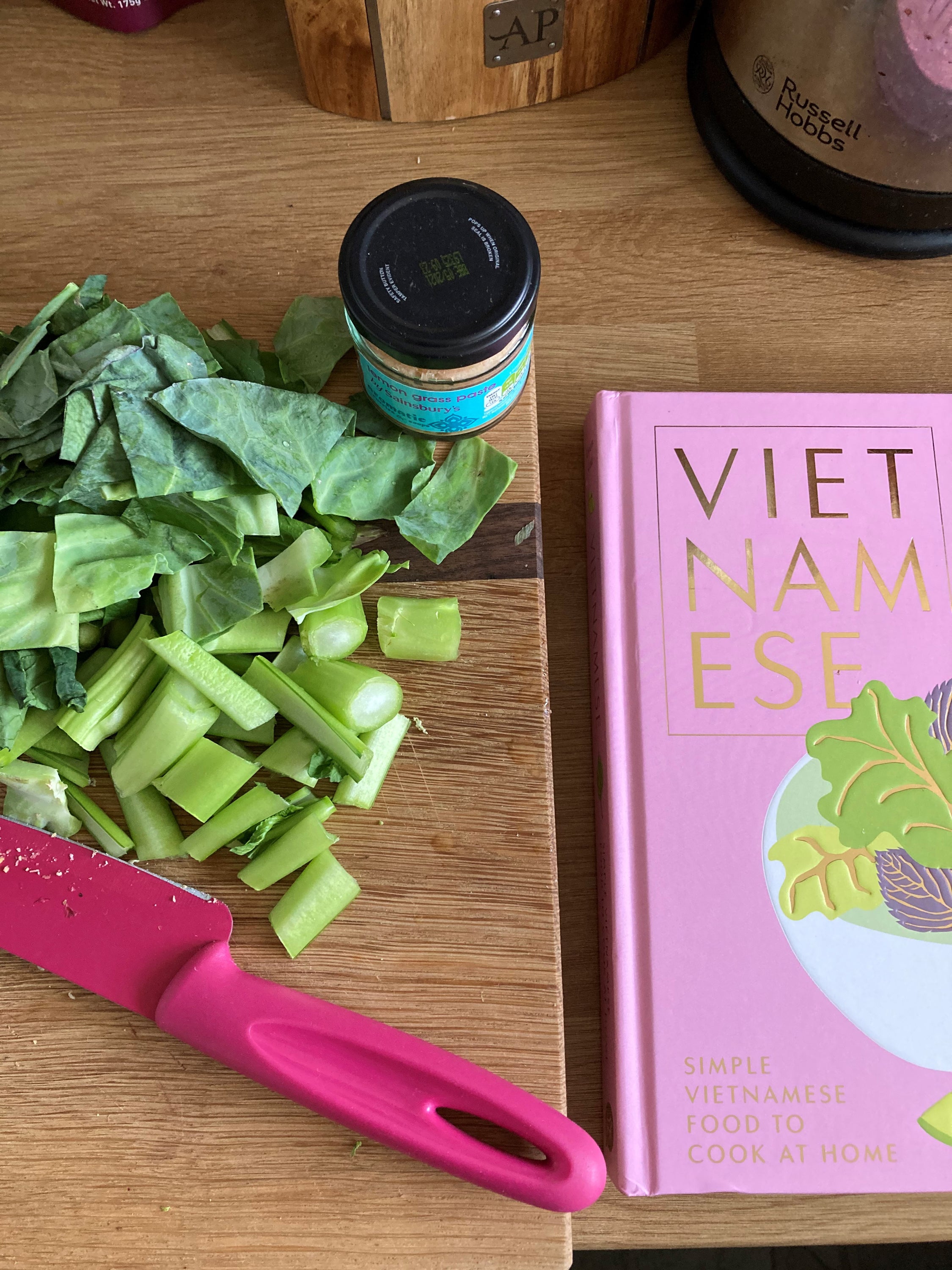

I start off slow with the stir-fried greens; a tangle of noodles, shards of pak choi and a sauce I didn’t even have to go shopping for (the ingredients – from maple syrup to soy sauce and sesame – are possibly already in your cupboards). It took literally 10 minutes to throw together, and the Thai basil I did go out and buy especially, was fully worth the trip (plus, it added an aniseedy lilt to Rachel Roddy’s Roman cherry tomato pasta a few nights later, when I’d run out of standard basil).

The ginger chicken I try next proves to be an alchemical triumph of caramelised brown sugar, chicken thighs and a hefty scattering of fresh ginger matchsticks. I grow sceptical when told to add a full teaspoon of freshly ground black pepper to the bubbling pan (surely not a full one?) but am an idiot to argue. It brings warmth and depth and almost tricks you into forgetting that really, it’s the fish sauce you should be applauding, because that’s the umami deliciousness holding everything together.

We crunch through spears of asparagus and broccoli on the side, a sign of Luu’s insistence to make things work for you. She just specifies “greens” – whatever greens you’ve got will do perfectly. Hence why my dodgy first crepe is folded scrappily into shells of iceberg and baby cos lettuce, and although I have a few strands of Thai basil left, and a little coriander and mint, I bump it up with chervil from a pot on the balcony too. Greenery of all kinds welcome.

We eat the lettuce-wrapped crepes in shifts, dunking them in a piquant fish sauce that runs down your wrists. They get crispier and crispier as I get more patient (ie quit poking around the pan) and the pan itself gets hotter and hotter, until the crepes crackle when they hit the plate. The piles of herbs, abundance of prawns and the elegance of the fish sauce in a blue and white china bowl, make this crepe supper feel special, memorable, but also achievable. And that’s the crux – Luu wants us to feel confident making these dishes, if not every night of the week, at least once or twice.

As a general rule, the dishes we cook at home on autopilot are the ones we grew up eating. Ask chefs, food writers and home cooks, “Who taught you to cook?”, and we almost always invoke grandmothers, nonnas, abuelas. Being a child, having a tea towel pegged to your top and a wooden spoon put in your hand by an elder, is practically universal.

They can hold the keys to our culinary heritage in a way parents – too close, too busy – tend not to. For many of us, it’s our grandmother’s recipes we long to record, and that we miss most desperately when we realise we’re grown up and have our own kitchens to use. Straying outside the culinary remits of our grandmothers can be difficult.

My childhood was cauliflower bakes, spaghetti bolognese (with grated cheddar, naturally), Chinese takeaways on Fridays (prawn crackers eaten straight from the bag) and roasts on Sundays. My granny made treacle tarts and elderflower cordial, bundt cakes, baked potatoes with boiled eggs, and chicken nugget bagels with peas and corn.

And yet, as I prepare Luu’s ginger chicken, and watch long strands of spring onion curl and twist as they’re submerged in a bowl of icy water, they make me think of my granny anyway, and how she’d use scissors to turn lengths of shiny wrapping paper ribbons into cascading spirals.

It turns out the act of learning something new, grasping unfamiliar methods and skills, or mastering a flavour combination that once seemed daunting, can make your brain turn to the person who taught you the first things, way back in the beginning.

‘Vietnamese: Simple Vietnamese Food to Cook at Home’ by Uyen Luu (Hardie Grant, £22; photography by Uyen Luu).

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments