The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

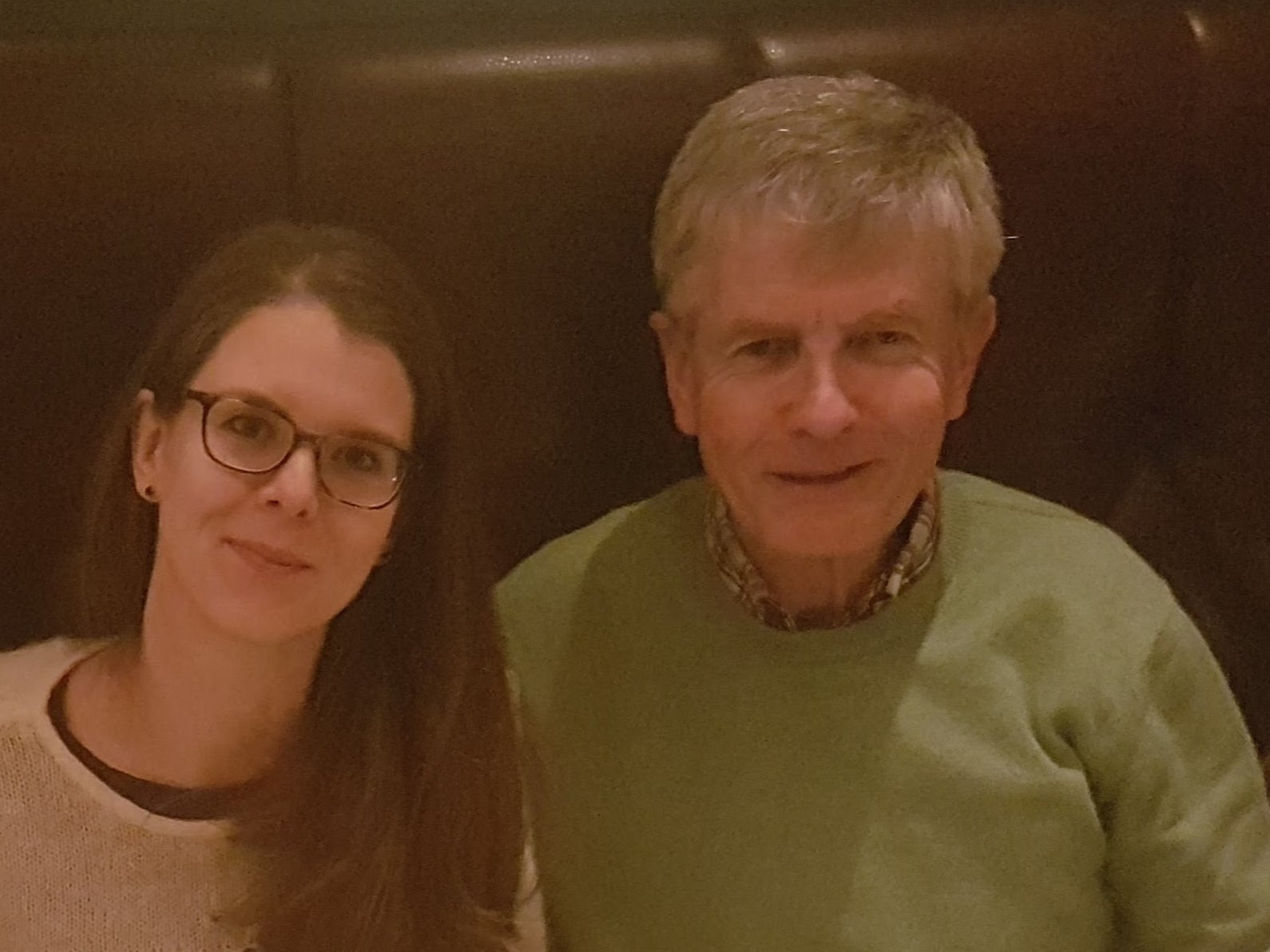

The single moment that changed my relationship with my father forever

Like many others, author Laura Coffey will spend Father’s Day remembering her dad who is no longer here – but sometimes it is the smallest acts which can leave the biggest and most important impression

I’m walking past a wall of posters for the Cezanne exhibition in London, on my way to the Underground. It seeps into me, this orange-ness, despite my efforts to avert my eyes. I drop them to the pavement but even though I won’t look at them directly, fat oranges sit on the edge of my subconscious all day. There’s an unexpected heaviness to oranges, a heft to them.

I know what Cezanne’s oranges are trying to tell me but I keep rolling them away from me. I am avoidant. I sulk. Then I do what I always do: panic and sweat and claw at the very last minute. I know I have to go.

The exhibition is completely sold out but a friend has a ticket for this afternoon. I make excuses, run from work, holding an umbrella against the rain. Suddenly, I’m there. I’m there in front of the Tate. I’m there in front of the oranges.

“With an apple, I will astonish Paris,” said Cezanne. His words are printed high on the wall at the entrance to the exhibition.

Apples. Oranges. The painter. My father. I cast my mind back, looking for the start.

Even though my father’s death three years ago was expected, it was still shocking. He had terminal cancer so we knew he had limited time, but towards the end, he went downhill very rapidly. The treatments had stopped working, he died earlier than the doctors hoped. In a way though, he was lucky, he got to die at home like he wanted. And I was lucky to be there for his final days. Not everyone gets that chance.

But afterwards, it felt like I was under snow. Where do people go when they die? I’m not sure. For a long time, I kept looking for him, kept wanting to tell him things, and realising he wasn’t there.

I’m not sure how exactly memory works either. But there’s a bright one, in hyper colour, that pulled me to the Tate on this day. It flashed into me when I saw those posters. It’s why I’m here. At a guess, I would have been between 10 and 13, awkward and teenager-ish. I remember standing in the queue for tickets outside the gallery in London for a long while.

Uncertainty mounting. Because I was alone with my father, and I was never alone with my father, ours was a classically gendered childhood – my brother went out with him on golf courses, I stayed with my mother doing whatever it was that girls did (this was never completely clear to me).

When I was a child, my father was mercurial, unpredictable, as quick to anger as he was to make a joke; he could be great fun and he could also be formidable. I found this disconcerting, and I didn’t know which way today would go. His anger always came with advanced warning signs: the very slightest grinding of his jaws, a tensing of the temporomandibular muscles, the habitual air-circling of his index finger as he spoke, twirling with increasing emphasis.

I wasn’t exactly scared of him, I held anger in my palms too and could radiate it back when needed, equal and opposite, but I was on guard, watching carefully, the way you’re supposed to train wolves never to take their eyes off you by behaving unpredictably.

So far the queue didn’t appear to be making him impatient and subsequently irritable, which it easily could have done. We were unused to London, to crowds, to day trips, to art, culture, galleries.

My father was mercurial, unpredictable, as quick to anger as he was to make a joke; he could be great fun and he could also be formidable

Once inside it was just me, my father and Cezanne. I’d been raised in the lonely green countryside, lacking in almost every cultural pursuit, other than Brontë-worthy damp walks. This was my first trip to an art gallery. Doubly uncertain once we were inside, not sure how to behave in this space of looking. Oranges spilled across tablecloths or were contained in bowls, mixed with apples and sometimes pears.

There was joy in them, that was something I knew for sure, was the extent of my art criticism, back then. My father seemed very happy looking at the paintings. And I was happy, looking with him. At him. Copying: how to peer at paintings, how to hold your arms behind your back, palm to knuckles, how to lean forward with intent. Relieved also. It seemed to be going well. He had chosen this, wanted for some reason to show me these paintings. I felt strangely grown up, his equal.

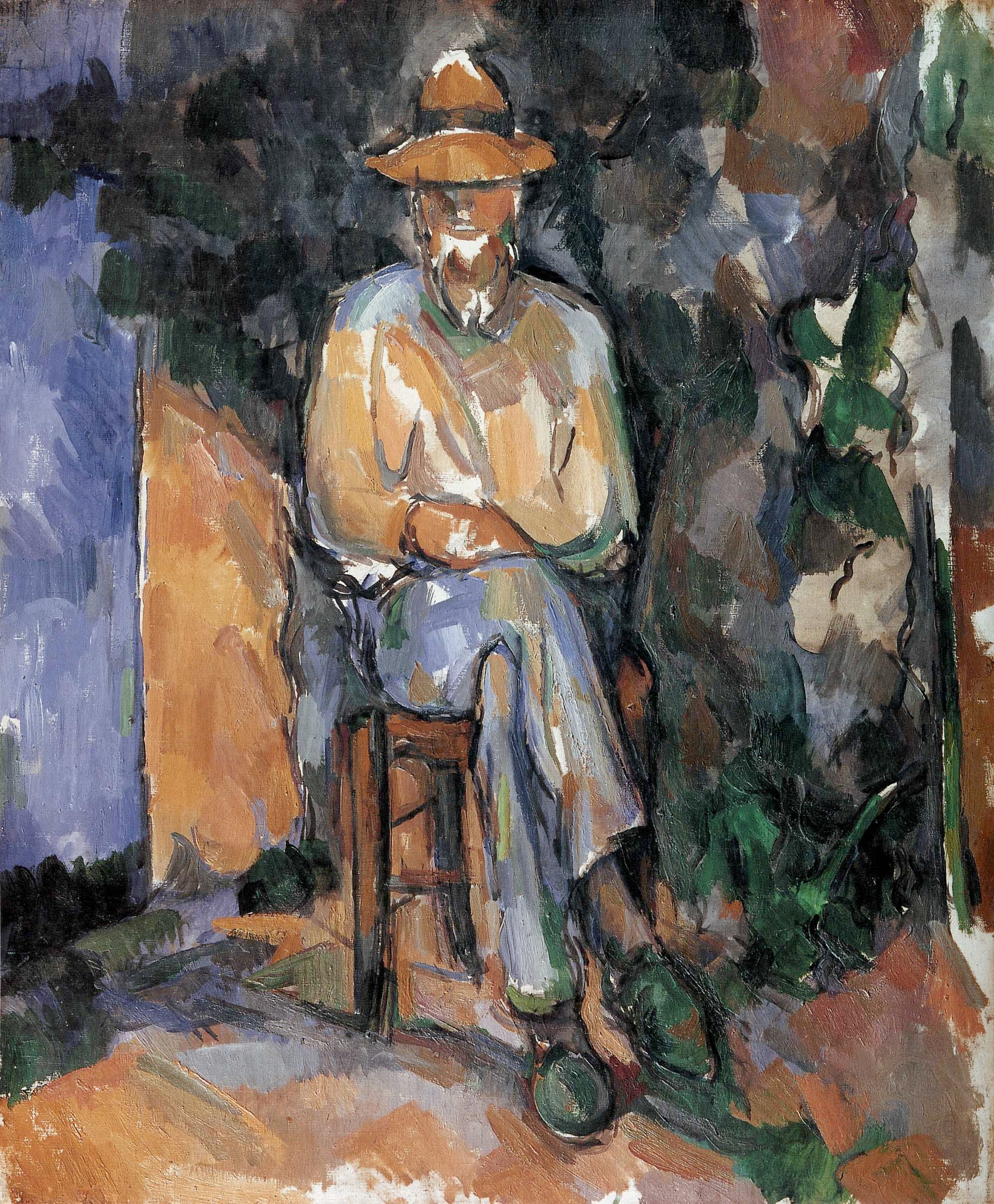

Afterwards, in the gallery shop, my father selected a print of The Gardener Vallier. On the train, he carefully carried the long cardboard tube. At home, the print was unrolled, framed, hung. It stayed in the sitting room for the rest of his life. When he died, in that room, the print was hanging on the wall next to him.

Prints and originals. Parents and children. Perhaps that’s too simplistic, reductive. Although he was original, my father. Not eccentric, but he had something I’d like to find a better word for than quirky. Character, I suppose. He was memorable, and not just to me.

After he died they came to me like arrows, the memories from his friends, his patients, his colleagues. He was, of course, more than his role of father, his personhood only fully revealed to me in his absence. I collected all the stories, reread the letters, messages, emails. Rereading and trying to understand, I suppose, that first text that was him. A revisionist history. Originals matter. You can see details in paintings that even museum-quality prints can’t convey. Details and scale.

Two years after his death, when I stand in front of The Gardener Vallier again, it's surprising. It shows a man in blue trousers and a yellow shirt sitting on a wooden chair against a dark background, but in the left corner, the blue of the trousers and the yellow of the shirt are echoed, suggesting perhaps a sympathetic connection between person and landscape. Far smaller than I expected, they must have enlarged it when they manufactured the print he bought.

The gardener’s eyes are hidden by a low-brimmed straw hat but nevertheless, there’s some kind of animation, an expectation perhaps of amusement, that I hadn’t noticed before, that hadn’t translated in print. And his foot too, held stiffly, at a slightly self-conscious, even theatrical, angle, and the shoe too, lighter than in the replica. It is, of course, emphatically not a painting of my father, but it is a portrait of my father that I see in it.

He sat for it too. My father, adopting the same pose, on a chair set out in my mother’s freshly dug vegetable garden. They must have brought the chair out specially. His foot is self-consciously held, pointing down. He’s smiling his crooked smile and wearing a blue jumper. It flashes into me, this photograph.

My brother had selected it for the back page of the order of service at the funeral. I look at the original painting, feet planted, this weird magnetic pulling feeling in my legs, standing exactly in front of it, refusing to be displaced. Letting gallery people flow around me. I stare and stare. Nothing resolves itself.

I go back to the oranges at the start and look at all the different versions, trying to imagine which of these paintings we would have looked at together. A nervous, long-legged girl in glasses with a clenching in her stomach, standing next to her father, so proud to be with him. I curate, decide which ones would have been there and look hardest at them, trying to figure out which ones he would have liked best. A scene of a clifftop village, the Frenchness screaming out from the canvas.

He loved France. I reject certain depictions of oranges and pears and apples, and am drawn to others. I refuse to look at the bathing paintings at all, believing they weren’t in the other exhibition. I have no evidence for any of these theories.

One still life of rolling fruit catches me for long moments. I look and look. Around me babies are wheeled and narrated to, a man talks loudly and earnestly at a woman, telling her the entire backstory of Cezanne’s life, giving a series of unsolicited observations.

I move away, don’t want to hear, don’t want any interpretation slicing between me and the looking. I go back to “The Gardener”. Searching. It is not a painting of my father, but somehow it is a portrait of my father.

The deadness is the poignancy. If I just wrote, oh this painting reminded me of my dad, it would be casual, but my dead father, now that has the weight of oranges. He can no longer remind me of himself so other things must.

There’s power in endings, in dead things, in dead things coming back to life. To haunt again, in this one, very specific way. I called to him, and he came. I found him again. Among the oranges and their joy.

This is how grief works. It holds you down but sometimes it holds you up, carries you in a rush across town to art galleries to look for ghosts in strokes of paint. It brings you back to love. It brings you oranges.

Enchanted Islands: Travels through Myth & Magic, Love & Loss by Laura Coffey (Summersdale, £16.99) is available now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks