Fashion's first selfies: It was a 16th-century German accountant who started the trend for style blogging

Instead of Instagram filters and digital cameras, Matthäus Schwarz's medium was watercolour on parchment

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The month of fashion shows for autumn/winter 2015 came to a close on Wednesday in Paris. The shows might have been offering up different ideas, but the scenes outside were much the same: gaggles of paparazzi, both amateur and professional, chasing rampantly after stylish show-goers – outré editors and Instagram “It” girls – to get that perfect street-style shot. These images live on through blogs and social media accounts and are used as a form of currency for those aforementioned style influencers, to show what they’re wearing to their millions of followers.

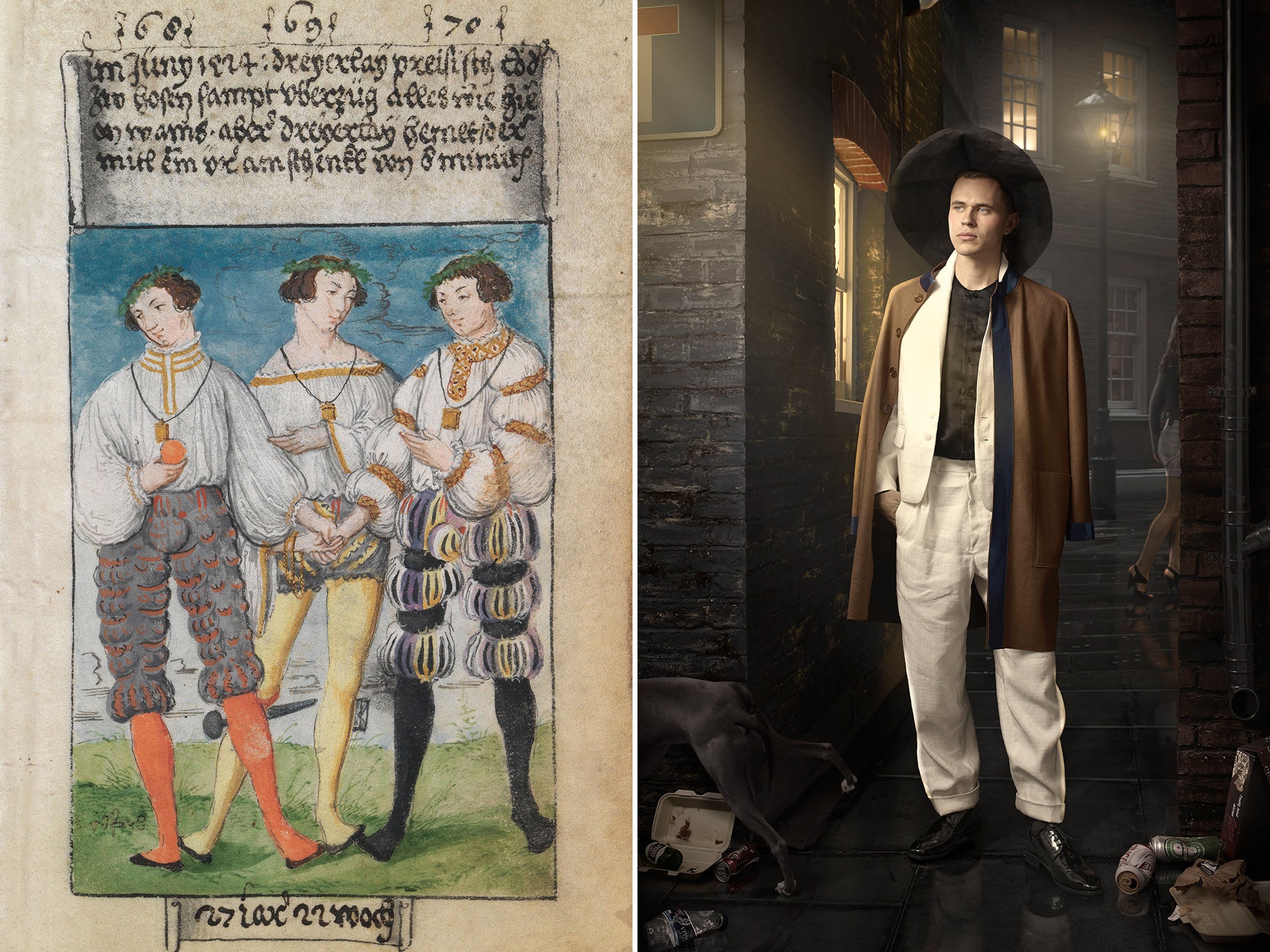

What we perceive to be a 21st-century phenomenon, though, turns out to be rooted in a much earlier and extraordinary example of style documentation. In an exhibition entitled A Young Man’s Progress at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, images from what historians have called the “first book on fashion”, created and commissioned by 16th-century German accountant Matthäus Schwarz, have inspired a new set of photographs of fictional male dandies, by artist-photographer Maisie Broadhead.

Schwarz, born in Augsburg in 1497, was an accountant for a family of wealthy merchants. He spent a large part of his income on clothing, and between 1520 and 1560, he commissioned artists to depict his outfits. He had the paintings bound into the Trachtenbuch (Book of Clothes). Instead of Instagram filters and digital cameras, Schwarz’s blogging medium was watercolour on parchment, as he conscientiously created the 16th-century selfies over four decades.

Many of his outfits were surprisingly elaborate – doublets and breeches with thousands of “pinks” (small cuts into fabrics) were an example of the cutting-edge fashion of the time. His outfits also communicated social or political significance; he wore a red and yellow outfit (echoing the colours of the Holy Roman Emperor’s flag) when Charles V returned to Germany, as a show of his allegiance to Catholicism.

Schwarz was entirely frank about his appearance, noting in one caption: “I had become fat and large,” going against the grandiose portraiture of the time that gave idealised versions of the individual.

Today’s form of style documentation is the opposite of realistic portrayal. Blogging what you wear has become big business. Fashion influencers in the past decade have collectively built up a multimillion- pound industry based on sharing their style with their fans and – as in fashion editorials – doctoring these images to conform to standardised beauty ideals is imperative. One single selfie on Instagram by these bloggers is often tied to commercial partnerships with brands, free clothes and a livelihood that didn’t exist 10 years ago. While Schwarz kept his documentation largely private as a vanity hobby, sensitive to his employers, today’s fashion bloggers expose themselves on a regular basis as a living.

One parallel remains, though, which is the idea of the democracy of fashion. Schwarz was bucking the convention of fashion being the preserve of the elite and the wealthy in a hierarchical society, but so too are today’s fashion-lovers on the periphery of the industry who make their presence known through their blogs and Instagram accounts.

Schwarz may not have had Instagram at his disposal, but you get the feeling that he would have loved garnering all those “likes”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments