The rise and fall of Gap, staple of 1990s normcore fashion

As Gap announces the closure all of its stores in the UK and Ireland, Olivia Petter reflects on what made the high street label a cult brand in the 1990s

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Think of 1990s fashion and Gap will immediately spring to mind. If not the brand’s cult logo hoodie, worn by everyone from Katie Holmes to Mark Zuckerberg, then surely one of its major celebrity campaigns, which were fronted by the likes of Naomi Campbell, Mila Kunis, and Cindy Crawford. Regardless of your opinions on the casual athletic-wear label, few can deny its seismic impact on the slouchy, denim-heavy aesthetic that dominated much of 1990s casualwear.

Which is why it felt like the end of an era when Gap announced the closure of all of its stores across the UK and Ireland. On Thursday, the company revealed that it would be shutting shop “in a phased manner” between the end of August and the end of September. As for the reason, a Gap spokesperson simply said the decision followed a strategic review of its European business. It joins a number of high street brands that have closed their shutters since the pandemic began.

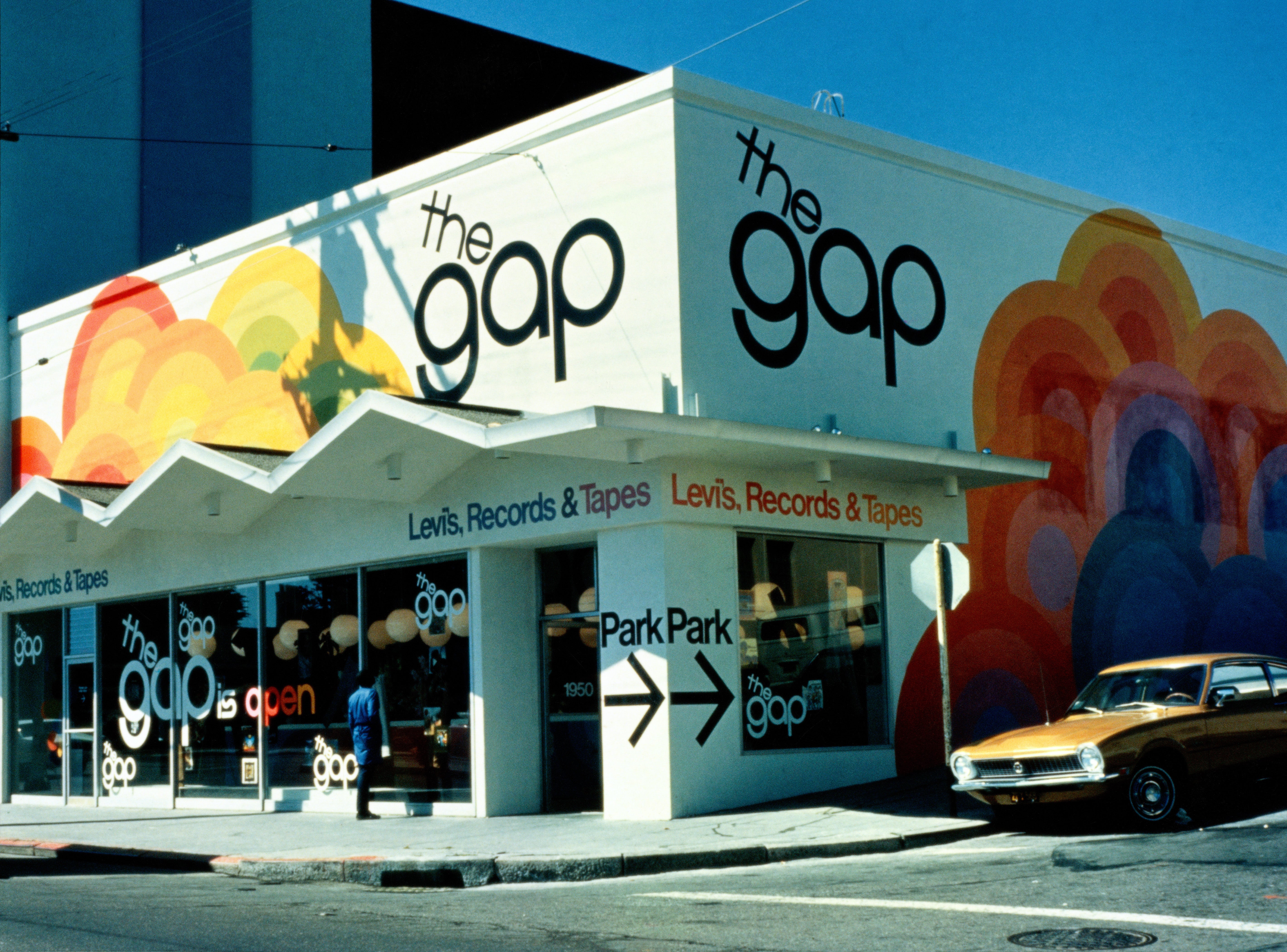

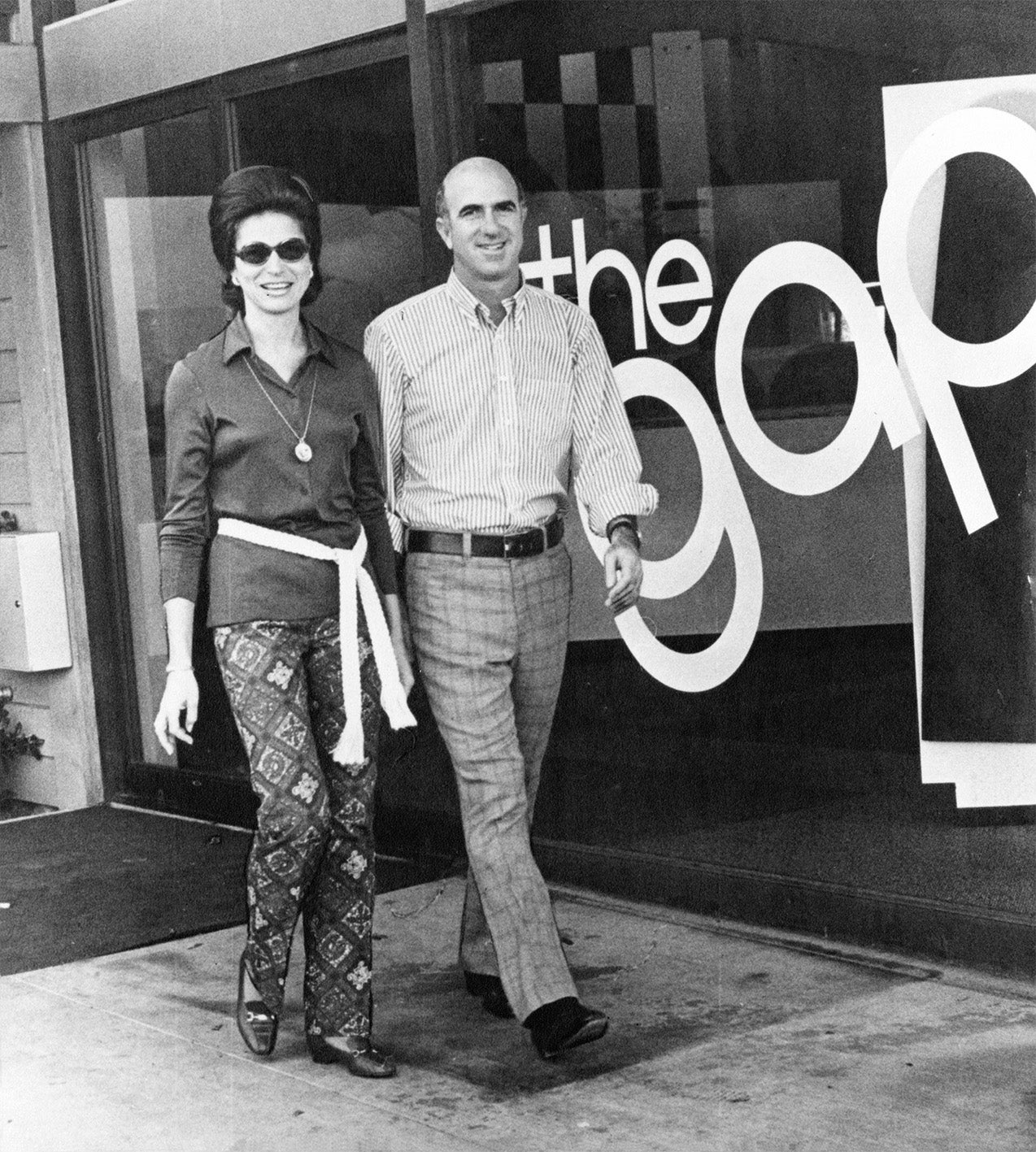

But how did this American label, launched in 1969 by Doris and Don Fisher in San Francisco, go from a humble hipster hangout to emblem of 1990s normcore? The Fishers launched Gap with one intention in mind: to help Don to find a pair of jeans that fit him. Together, the couple raised more than $60,000, which they used to open their first shop on Ocean Avenue. The name Gap was used in reference to the generation gap. At the time, the concept of separate styles for young people and their parents’ generation was nascent, and Gap sought to move away from models that put older shoppers at the forefront, instead focusing on tapping into the youth market.

The first Gap shop sold Levi jeans and vinyl records, but by the 1970s, the brand had exploded in popularity and the Fishers soon opened a second store in San Jose, followed by a headquarters in Burlingame, California. In 1974, the first Gap-label products started to appear in stores, and other brands were slowly phased out. By the 1980s, Gap had expanded exponentially. The company had gone public in 1976 and in 1983, it added another brand to its roster, purchasing safari and travel-themed store, Banana Republic. Three years later, Gap opened its first childrenswear store, Gap Kids. It then started launching stores outside of the US, opening a London outlet in 1987.

It wasn’t until 1988, however, that the brand chose to replace its rounded logo, that simply read “The Gap”, with its now famous navy blue and white logo: a square with the words GAP emblazoned across in a bold white typeface – dropping the definite article and becoming simply “Gap”. It was simple. It was classic. It would soon become iconic.

As child growing up in London in the 1980s I remember clearly the moment when Gap opened its first stores in London

“As a child growing up in London in the 1980s I remember clearly the moment when Gap opened its first stores in London,” recalls Harriet Atkinson, senior lecturer at the Centre for Design History at the University of Brighton. “I remember the excitement of being able to get hold of T-shirts and jeans that I’d only seen in films and TV shows. Gap clothes were within reach, they were fashionable but not outlandish - my mum approved! - and they were reasonably priced.”

That’s the thing about Gap. The clothes weren’t just cool and comfortable – they were also affordable to the young people who wanted to wear them. “Gap joined an ever-expanding group of youth clothing brands on UK high streets: Topshop and Topman, Dorothy Perkins, Warehouse, Miss Selfridge,” adds Atkinson. “But while they changed their styles to fit with emerging trends, Gap stuck to a formula of neutral shades and clothes that didn’t change much from season to season, which worked well at the time.”

The clothes were also well made, which widened their appeal even further. “Gap always felt truly inclusive,” says Emily Gordon-Smith, director of consumer product at Stylus. “It was an entirely accessible aesthetic but at the same time was cool. Simple, clean-lined, authentic product supported by those ad campaigns featuring creative individuals such as Sheila Metzner and Spike Lee wearing the label’s iconic khakis and pocket tees. And of course, there was the kidswear. If your baby didn’t wear Gap in the 1990s, I am not sure what they were wearing.”

The label soon occupied a place on the high street that had previously been dominated by reliable mid-range brands like M&S, which also sold casual staples but was not succeeding in keeping relevant to young people. “Gap also appealed to older people who weren’t yet ready to embrace middle age,” adds Atkinson. “That branding – the blue and white square – soon became ubiquitous on high streets up and down the country: a sign of reliability – you knew what you were getting.”

It was around this time that Gap’s most famous campaigns launched, including ones starring Kirsten Dunst, Jessica Alba, and Salma Hayek. It wasn’t just women, though. Famous faces like John Mayer and Chris Evans also fronted Gap ads, pushing the brand even deeper into the 1990s zeitgeist.

But the brand’s shift into fashion’s upper echelons came when supermodels wore Gap white denim jeans and woven shirts on the cover of Vogue Magazine’s 100th anniversary issue in 1992, a testament to the label’s sartorial significance at the time, and one that led to Gap Inc’s stock price reaching an all-time high of $59. By the end of the decade, The San Francisco Chronicle had named Gap Inc. “Company of the Year” out of 500 top companies in northern California.

However, things started to take a turn in 2006, when Gap was one of the retailers targeted in a series of labour rights protests after reports emerged of poor working conditions in the brand’s factories. While the brand has remained a strong presence in the industry since then, it has never reinvigorated itself to acquire the same cult status it maintained in the 1990s.

The falling out of favour continued, despite an attempt in 2017 to reinvent itself by appealing to younger nostalgia-seeking consumers with a 1990s-themed collection, which comprised beloved items like Gap’s oversized sweatshirt, carrot denim jeans, and khaki trousers. The campaign was even fronted by former Gap 1990s stars, like Campbell and model Chelsea Tyler, whose father, Aerosmith’s Steven Tyler, starred in a Gap advert in 1997. Lizzy Jagger, Evan Ross (son of Diana Ross and husband to Ashley Simpson), and Rumer Willis also featured in the ad.

Gap’s clothing started to look plain and boring; probably because it’s so ubiquitous

While many of us will remember proudly donning our Gap hoodies, paisley headscarves and tank tops in our youth, sadly, an archive collection was not quite enough to help Gap secure a place in the modern world. Online sales plummeted and it seemed like the allure of the collection was not quite enough to tap into older generations’ nostalgia, nor did it seem current enough to entice younger shoppers, who probably didn’t recognise many of the faces in the campaign. In 2019, it was reported that the Fisher family had lost $1bn. The following year, Gap reported a 43 per cent decline in first-quarter sales, leading Forbes to declare that the company had officially lost its relevance and failed to keep up with fashion’s ever-moving trend circuit, relying on tired and outdated aesthetics instead.

“There are now lots of brands on UK high streets, like H&M and Cos, that do similar things to Gap but manage to keep up with trends across the age categories,” says Atkinson. “In comparison, Gap’s clothing started to look plain and boring; probably because it’s so ubiquitous.”

Despite all this, it seems that Gap still holds a place in the US retail market. Last year, the company announced a 10-year collaboration with Kanye West for a new clothing line called Yeezy Gap. The line launched in June this year and consisted exclusively of a $200 blue recycled nylon puffer unisex jacket. It sounds simple enough, but the jacket has proven very popular among younger shoppers, and last month, American financial services company Wells Fargo predicted that Yeezy Gap could generate almost $1 billion in sales for the company.

And so, it seems that even though its UK stores will soon be shutting their doors once and for all, Gap’s legacy will go on. Regardless, as is often the case with 1990s trends, us Brits will always look back on its golden era fondly.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments