Yves Saint Laurent's 1971 collection shocked the world - but changed the direction of fashion

A scandal erupted at the Rue Spontini in Paris on 28 January

Yves Saint Laurent's 1971 spring haute couture Forties show – the collection which at the time was the subject of critical carnage – is so embedded in fashion consciousness that I'm racking my brains to think of any show that's been more continuously influential in the intervening 45 years. It hit me yet again when Sarah Burton showed me around her Alexander McQueen pre-fall collection a few weeks ago: there on her rail was a short green fur chubby jacket, a dress embroidered with lip-prints, a line-up of strappy velvet platform sandals. It's there, too, in Alessandro Michele's Gucci collection: a dress with a trompe l'oeil gold sequin ribbon in the shape of a bow sewn into the bodice, one of his most photographed hits for spring. Not to mention the endless glittery glamour that Hedi Slimane has been requoting to such commercial success at Saint Laurent.

None of it could exist without the scandal that erupted at Yves Saint Laurent's salon at the Rue Spontini in Paris on 28 January 1971. It was an event which crossed a cultural rubicon, dividing the generations. There was no doubt on which side the ladies of the establishment press belonged, as they watched the 84 looks flirt by. What they saw, among the sexy crepe draped dresses, the wide-shouldered tailoring, satin jackets, boxy dyed fox fur shrugs, turbans and four-inch platforms was a bunch of tarts from the Rue Saint Denis; their own memories of occupied Paris being hurled back in their middle-aged faces.

Eugenia Sheppard of the International Herald Tribune went for the jugular. "What a relief at last to write about a collection which is frankly, definitively and completely hideous," she fulminated. "I'd say it's suicidal." Alison Adburgham, The Guardian's fashion editor, opined: "Nothing could exceed the horror of this exercise in kitsch." Paris Jour condemned "these... deliberate, sad and demoralising excesses". Vitriolic headlines rained down: "Yves Saint Laurent Insults Fashion"; " Press Scandalised by Saint Laurent Show". And, most tellingly of all: "Sad Reminder of Nazi Days".

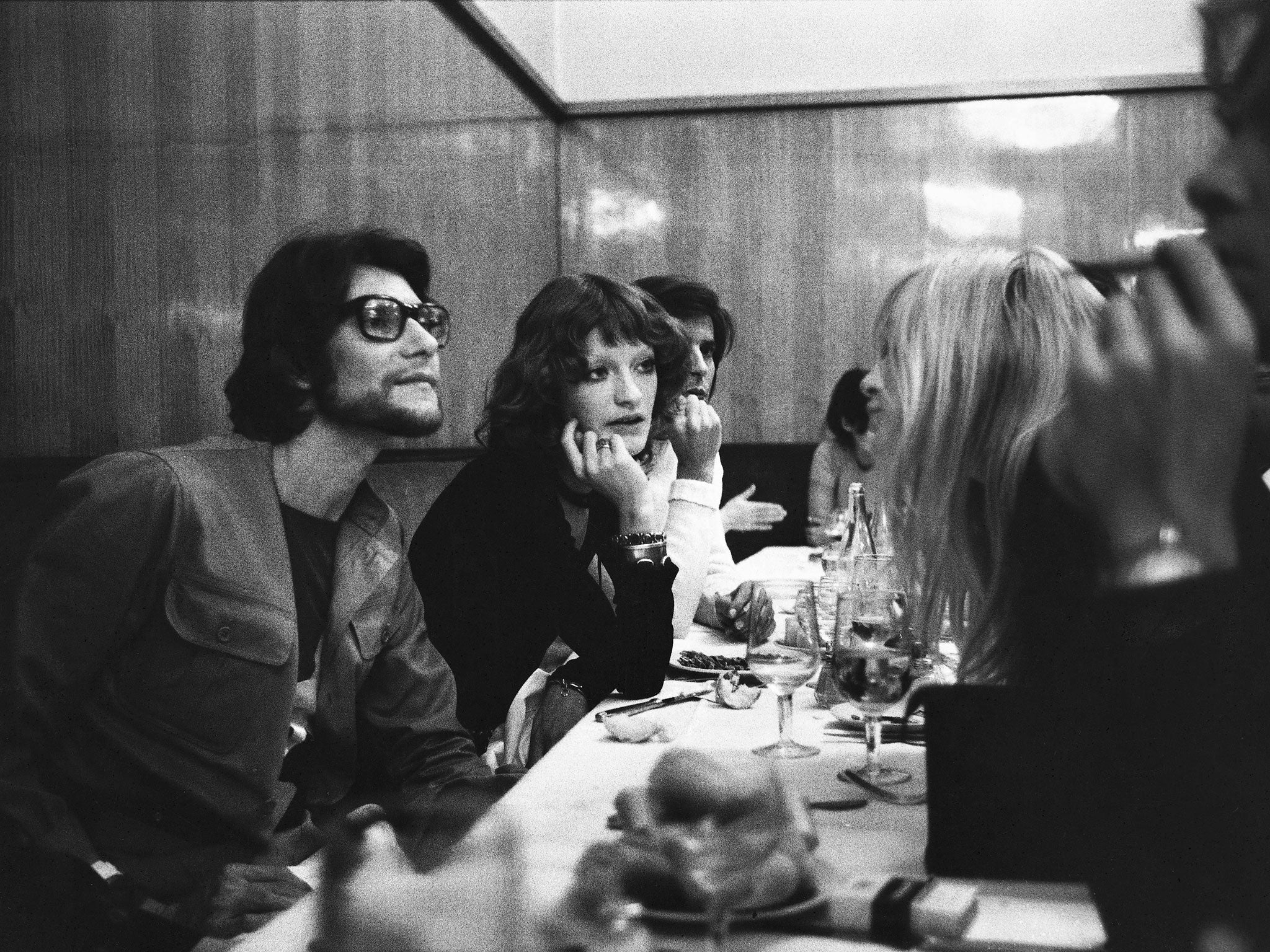

It didn't look like that to the 22-year-old girl who was sitting in the front row dressed in a Forties crepe dress she'd picked up from Portobello Market, a shaggy black, second-hand fur, a red velvet turban and platforms. " I almost felt like I was opening my own closets and those of the girls who shared my taste," Paloma Picasso remembered. Saint Laurent had recently met Picasso and was mesmerised by her put-together flea-market style. As it turned out, she was the key to the whole thing – the link between Yves Saint Laurent and a rising pop-culture which was being generated by kids too young to remember the war.

Picasso sat there astonished to see her cheap finds sublimated into an incredible haute couture collection. "I was amazed. I wasn't really thinking in terms of fashion. As far as I was concerned [dressing in Forties style] was just a spontaneous, almost crazy urge. I never imagined there would be any consequences."

At 35, Saint Laurent had spent his childhood in Oran in Algeria and had no memory of life in occupied France. Faced with a critical disaster, accused of bad taste, and panned for being derivative, he fought back. He called his attackers "narrow-minded petty people paralysed by taboos. But I am also stimulated because that which shocks is new. Perhaps it did not please certain press or American buyers – but it pleased youth, and that is what counts for me. Fashion is a reflection of its time." And then he never said another word about it.

Looking back, it's interesting to analyse just how much Saint Laurent's collection really was a conduit of the times. Fashion critics normally parse collections through the prism of the quality of techniques and the originality of the inspiration – as if the designer is a sequestered genius, drawing down visions from on high. That was certainly the way Paris haute couture was always judged, with the added condition that the visionary should also act as service-person to the requirements of a rich clientele. But the reason Saint Laurent's collection stood out was that it connected – knowingly or not – with a wave of youth reaction against the bleak times which had just hit, escaping into the glamour of Hollywood movies of the 1930s and 40s. Paloma Picasso wasn't an eccentric lone muse, but part of something which was already happening against the god-awful backdrop of 1971.

That she was hopping across the Channel, buying her inspirational clothes at Portobello market, and going to art-house showings of classic movies was no coincidence. London kids, art students and designers were already deep into "retro". A whole year earlier, Ossie Clark had shown his 1940 "Tarts" collection for Quorum – all puffed sleeves and bias-cut mini-florals on a wildly dancing group of models – including Amanda Lear, Patti Boyd, and Gala Mitchell – at Chelsea Town Hall. Barbara Hulanicki, pioneer of alluring fashion-kitsch, had built her entire Biba teen empire on nostalgia for the 1930s and 40s. Marc Bolan was out there vamping on Top of the Pops to "Hot Love" in silver satin suits and feather boas. When David Bowie released his film-clip for "Life on Mars" in December 1971, he dressed in the ice-blue Forties suit with platform shoes which fashion has never stopped venerating. The look was designed by Freddi Burretti, but it might almost have stepped straight out of Saint Laurent's collection.

It's debatable: did the British children of glam-rock know anything about what Yves Saint Laurent was doing in 1971, or vice-versa? What's certain is that the women who were horrified by Saint Laurent's collection that fateful day were completely oblivious to the new world that had captured the imagination of a generation. It was they who belonged to an old world, on the way out.

Saint Laurent had captured that zeitgeist so accurately that he was vindicated within months. Francine Crescent, editor-in-chief of Paris Vogue, gave the collection to Helmut Newton to photograph – forging images that have been indelibly burned into the mind's eye of every fashion photographer, editor, designer and fashion-lover since. The collection changed the direction of fashion, feeding ideas that had come up from what we now call "kids on the street" into the rarefied world of haute couture, and thence into the mainstream. It's a flow which has never been reversed. Nor has the way that the contents of that controversial collection have cascaded through the hands of designers down the decades: Miuccia Prada, Tom Ford and Marc Jacobs in the 1990s and 2000s; Sarah Burton, Alessandro Michele and Hedi Slimane now. Has there ever been a collection in history which has lasted that long?

Sarah Mower is chief critic of US Vogue.com

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks