Rough trade: How two brothers rose from gangsterland to create the fashion brand Gio-Goi worth £40m (then promptly lost the lot)

Bulletproof vests, raves, Strangeways… few fashion pioneers have quite the history of the Donnelly boys. Nick Duerden hears how the brothers rose from gangland beginnings to make £40m with a streetwear brand that captivated everyone from Sir Alex Ferguson to Kate Moss

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Anthony Donnelly, who in certain circles warrants the prefix "infamous", leans forward, arms on thighs, his blue eyes staring out from beneath the peak of his baseball cap. He says, in a voice so low you have to lean in close to hear him, "You know, a lot of people say, when they meet us, that they had no idea we were so nice, so approachable…"

The implication is that he and his brother Chris, co-founders of Gio-Goi, the Manchester fashion label that, at its height, was raking in £40m a year, have reputations – the sort supposedly linked to guns, gangs and drugs – that have made people rather scared of them.

I certainly was before meeting them, and with good reason: I've just read their memoir, Still Breathing, an oral history that charts their improbable rise from the sprawling Wythenshawe council estate to international fashion guru-dom, via European road trips robbing shops and safes, undercover police surveillance, and so much local aggro they felt it necessary to wear bulletproof vests to work. "We were not nice people," Anthony admits early on in the book.

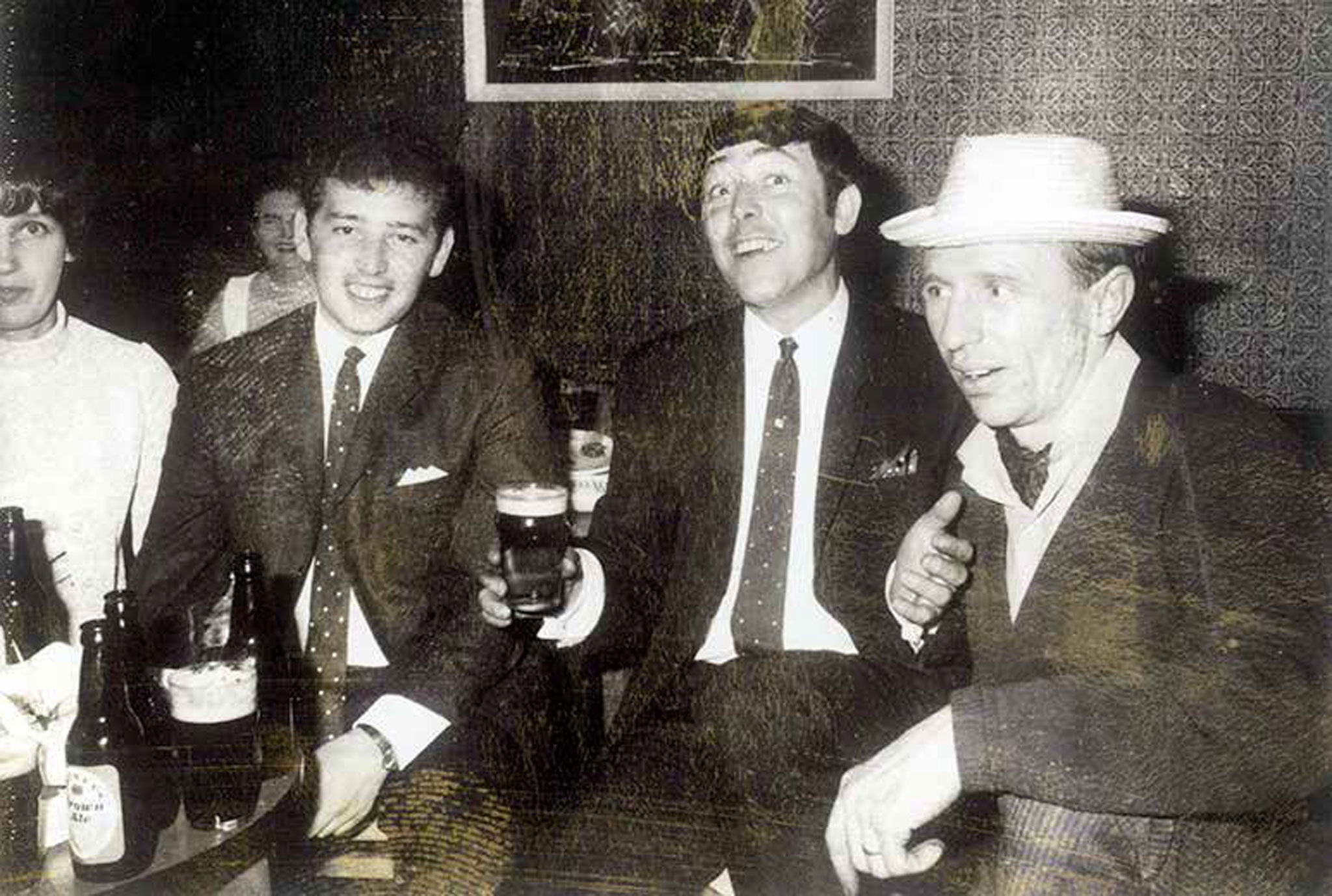

Born into a family linked to the Quality Street Gang, which cultivated a Krays-like status throughout the North in the 1960s and 1970s, in the flesh, the Donnellys come across much as they do in their book: rogues of the curiously lovable kind. They are funny, too: the memoir, though riven with violence and drug-fuelled calamity, is laugh-out-loud, and throbs with the kind of opportunistic entrepreneurial spirit it's hard not to admire. They were born with little more than nothing, and went on to make everything (and lost everything again – but we'll come to that).

"I don't think there is any shame in it," Anthony states of their story, sipping on mineral water with no ice because, as he comments to the waitress, "I'm cool enough already." We are sitting in the lobby of the magisterial St Pancras Hotel in London, me, Anthony, the more relaxed and friendly Chris and a silent young bloke called Danny who, at the end of our interview, gets up and photographs us all in a tight clench, whether I like it or not. "If you've got a story to tell," Anthony says, "tell it well. We have."

It is, by any stretch of the imagination, a fantastical tale. Their father, Arthur, was a scrap-yard merchant who made a fortune selling engine parts around the world; police believed he was also a gang leader and counterfeiter. (He was eventually convicted on drug charges.) By their late teens, Anthony and Chris, now 48 and 45, were bootlegging band T-shirts, and selling them outside concert venues across Europe.

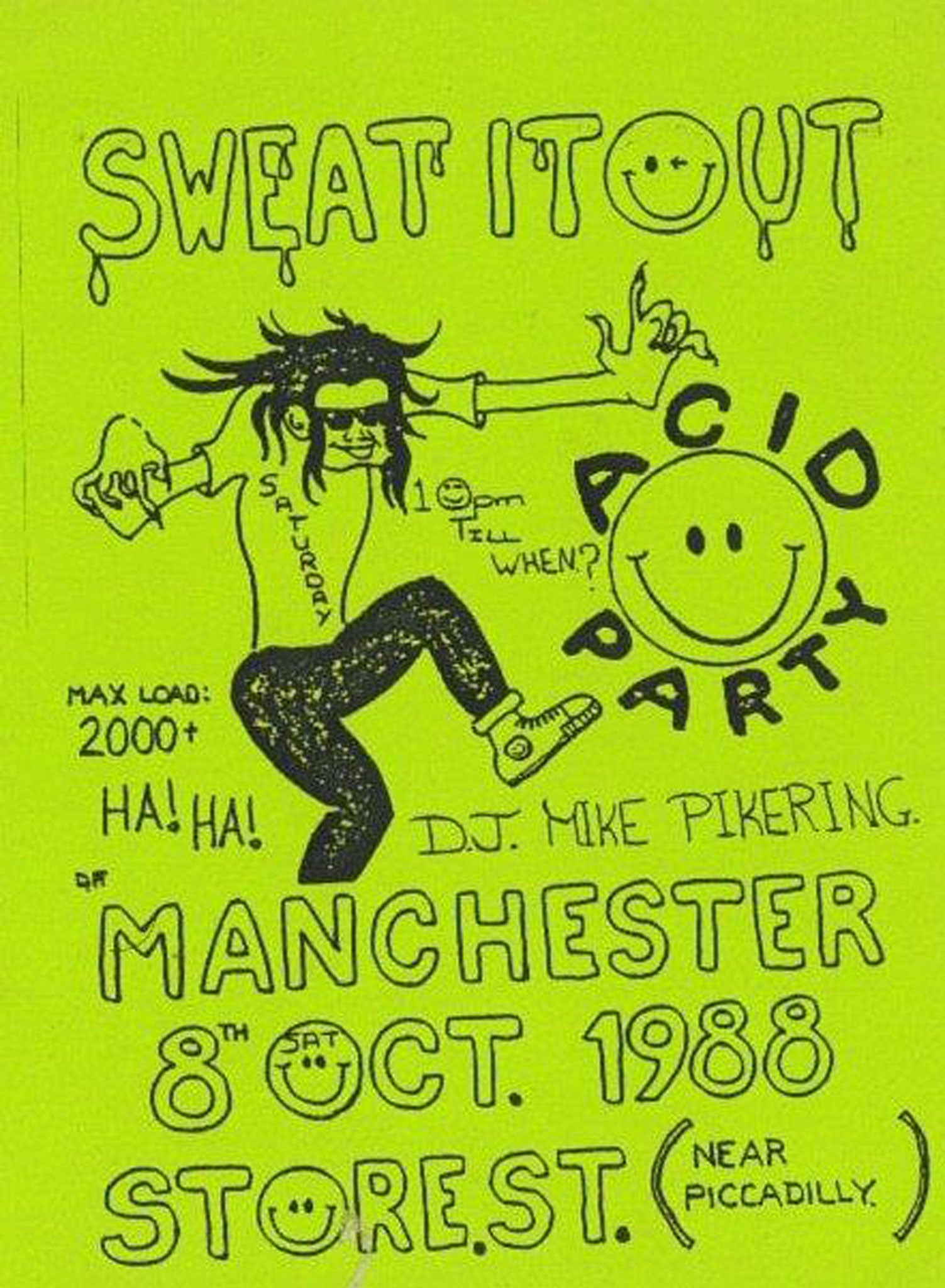

This was the late 1980s, a time of Acid House and the rise of Madchester, the music scene as dominated by fashion and Ecstasy as it was by the Stone Roses and Happy Mondays. The Donnellys, quickly tiring of bootlegging, went along for the ride, roping in a couple of designers, and started making their own clobber under the label Gio-Goi. (The two words were plucked at random from a Vietnamese dictionary, the first appealing to Anthony because it reminded him of Giorgio, as in Armani.)

They befriended, and subsequently dressed, many of the Madchester acts, and soon all sorts craved their sartorial swagger: snooker's Alex Higgins, boxing's Nigel Benn. Even the then Manchester United manager Sir Alex Ferguson took to wearing a Gio-Goi beanie hat at games.

Within a couple of years, the label was being hailed as Manchester's rough-hewn equivalent of Yves St Laurent, and clearing, they claim, £3m a day. Not bad for a pair of siblings who, as they admit, "didn't know our arse from our elbow".

But, Anthony says now, their success didn't surprise them. "We come from a very hard-working background, so when we put our minds to something, we expect to do well. Very well."

In the space of three seasons, they went from being a £300,000-a-year operation to a £19m-a-year sensation. Vivienne Westwood proclaimed them "ambassadors for a generation". This, says Chris, was "satisfying".

But success didn't rein them in and suddenly render them sensible businessmen. Anything but. Crucial to the label's branding were the garrulous brothers' presence at every social event. They didn't just make, wear and sell Gio-Goi – they lived it.

Life was a perpetual party, and they conducted most of their business at night, in bars and clubs, drunk and wasted. They had long been organising all-night raves – by their very nature, illegal – and they say the police became increasingly convinced that Gio-Goi was merely a front for something more subversive – specifically, drug-dealing on a major scale.

A certain awkward etiquette (and cowardice) prevents me from asking them outright whether the police's suspicions – which the brothers have always denied – had any substance. But, either way, in 1994 everything came crashing down when they were arrested, the label left to flounder as they focused on two things: asserting their innocence and maintaining their freedom.

"[The police] had nothing," Anthony says, "and all charges on Chris were dropped." Anthony himself was later charged with supplying diazepam ("A class-C drug," he points out), and sent to Strangeways for nine months. In a book careful not to corroborate anything that might be used in evidence against them, the passage on his time in prison is revealing. Fellow inmates, he writes, "told me [that] whatever I needed, whatever I wanted, was available to me. Within 48 hours I was having my own way in there."

This kind of treatment, I suggest, is surely only afforded to the most respected, and consequently feared, of underworld types, isn't it?

Anthony, already wincing the way one would when about to face root-canal treatment, says he is unhappy about the way the conversation is going. He isn't used to being interviewed – both brothers have avoided it over the years – and so now, politely but firmly, lets it be known that we should move on. "I'm not offended by your questions, they're good questions," he says. "But I feel quite guarded about certain things. We're private people. We stay private."

Chris elaborates. "It's all the shit we've gone through that has made us guarded, you see?"

"It's a trust issue," Anthony says.

Their awkwardness is perhaps understandable. Things could get compromising. Which makes one wonder why they decided to commit their story to page in the first place. Anthony, still wincing, explains that the lawyers have gone through it, that everything recounted is already in the public domain, and that, "We've protected our friends, we've protected ourselves. So we don't anticipate any problems arising from it."

OK, but any book with the tagline "From Organised Crime to Kings of Fashion" is bound to raise eyebrows. What if the police read it and wish to discuss the contents? "Well, they know where we live," says Anthony.

After he came out of prison, the brothers fell out ("Over money, probably"), and did other things: Chris renovated houses, Anthony, ever enigmatic, "met some people offshore and did a couple of things out of the country". They ultimately reunited because, says Chris, "We're brothers: we fall out and we fall back in again."

When Gio-Goi resurfaced in 2005, they swiftly reworked their magic and started dressing a new generation of pop stars: Lily Allen, Pete Doherty, Plan B, Arctic Monkeys. Soon, they were making £40m a year – so set their sights on £400m. For this, they needed serious investment, and got it from a company called Melville Capital.

But the union was not to be straightforward, and there were frequent clashes over respective working methods. The Donnellys' "arse from elbow" approach, which had served them so well in the past, didn't float with the respectable Melville types, and both parties eventually lost all enthusiasm. In January this year, the label went into administration.

But, Anthony insists, this isn't the end of the story. The label is owned by JD Sports now, and is planning a major comeback, with the brothers in a supervisory role, while they focus the bulk of their attention on their new label, Your Own, a growing concern with aspirations to go global. "We want this to be a £1bn company eventually," Anthony states.

Ask whether anyone with a past as questionable as theirs can ever run a truly reputable business, and they point to US rappers such as 50 Cent and Jay-Z, both of whose own pasts, they say, are not dissimilar to theirs. "And it never held them back, did it?"

Besides, Anthony adds, things are different now. They are middle-aged; they both have families; life is more settled. In the book, he says: "I would like to apologise for any pain I caused when I was younger, and for the things I should have done that I never did."

"Look," he says to me now, "let me make it clear to you, in case there is any doubt. We are not endorsing any of the things we have written about in the book. These were the cards we were dealt, and we played with what we had. But if there is any message in the book, and I hope there is, then it is this: that out of bad things can come good. Do the right thing, work hard, make it happen for you, and leave things behind. We did. Know what I mean?"

'Still Breathing' is published by Black & White Publishing, priced £20, on 7 November

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments