Is Saint Laurent creative director Hedi Slimane dishonouring the great man's legacy?

It’s the legendary French fashion house that produced some of the defining looks of the 20th century. But does its new direction dishonour the memory of its great founder, asks Alexander Fury

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In Paris, a house has been ripped apart, quietly gutted, over the past three years. It's the house of Yves Saint Laurent. I'm not just talking about the metaphorical house, the label that bears his name and is helmed by designer Hedi Slimane. Under Slimane, Yves Saint Laurent was rebranded simply – almost biblically – Saint Laurent. Its entire visual identity has been reengineered. A storm of protest ensued: one label made a killing with T-shirts bearing the slogan, "Ain't Laurent without Yves," rendered in the house's new typeface.

The house I'm talking about isn't that. It's an actual house, one of those storied, stuccoed mansions the French call hôtels particuliers. The building is to house Yves Saint Laurent haute couture, revived 13 years after the retirement of its founder, and seven years after his death. The mansion has been remodelled, like the rest of Saint Laurent, in Slimane's image. Not just the image he determines – Slimane designs everything, from the Saint Laurent stationery to its shop interiors – but in his physical image: tall, skinny, monochromatic, Parisian. Slimane was born in the city's suburbs in 1968, the year of protesting students. Over in the moneyed 16th arrondissement, Yves Saint Laurent would dedicate an haute couture collection to them.

The new house isn't in the 16th – nor the 8th, where Yves Saint Laurent's couture operation moved in 1974 (the salons are now a museum dedicated to him). It's on the Left Bank. Saint Laurent opened his first shop there in 1966 – the first ready-to-wear boutique bearing a couturier's name: Saint Laurent Rive Gauche. In his two years as head of Christian Dior, he also drew inspiration from the black-clad Saint-Germain existentialists for a 1960 collection so radical and forward-thinking that it got him the sack.

Slimane worked for Dior, too – for longer, and left of his own accord. He headed the label's menswear from 2000 to 2007. And, like Saint Laurent, Slimane's work at Dior was influential, even revolutionary. His skinny tailoring, fitted to even skinnier models, changed the way the entire fashion industry thought of masculinity – and the way legions of high-fashion and high-street labels cut their suits.

The power of Slimane's fashion was in the overall look – the silhouette, the specially cast models (many unknown), the soundtracks and sets. The designer Karl Lagerfeld, enamoured of Slimane's vision, lost six stone to fit both the clothes and the aesthetic. Slimane's former assistant, Kris Van Assche, now designs Dior Homme in much the same vein.

If Slimane can lay claim to defining much of the wardrobe of 21st-century men, Yves Saint Laurent undoubtedly did so for their female predecessors. He is the most important fashion designer of the past 50 years. "I tell myself that I created the wardrobe of the contemporary woman, that I participated in the transformation of my times," Saint Laurent said, upon his retirement. Those sound grandiose statements, but they're true.

Herein lies the significance of Yves Saint Laurent. He designed the first high-fashion trouser suits and safari jackets. He invented designer ready-to-wear, giving it a prominence previously only enjoyed by couture. In the 1980s and 90s, Saint Laurent allowed colleagues to oversee those ready-to-wear lines, focusing his attention purely on couture. In 1998, he officially bowed out of ready-to-wear entirely, passing the reins of his womenswear line to Alber Elbaz, now creative director of Lanvin, and his menswear to Slimane. It was Slimane's first job heading a fashion house.

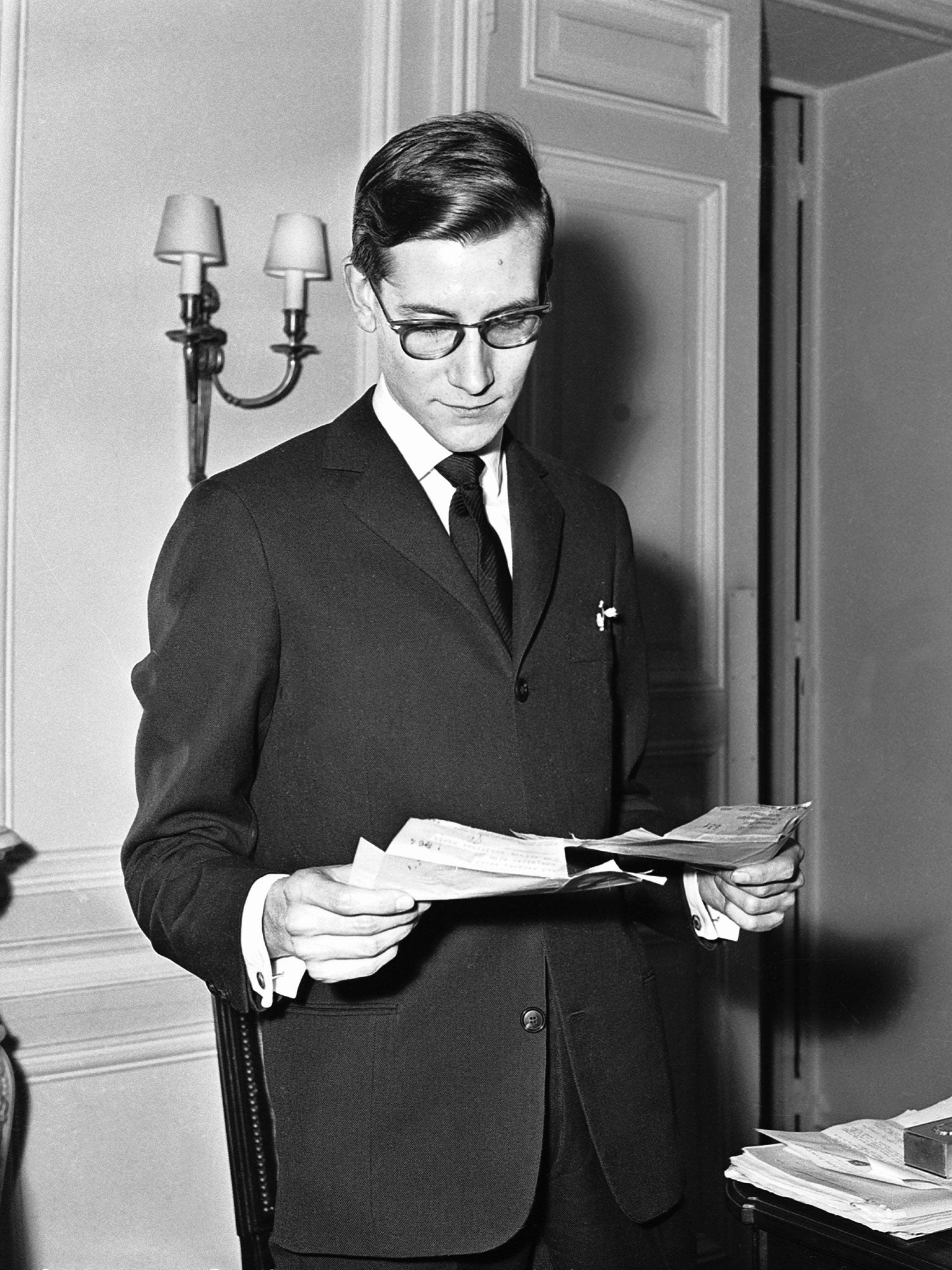

Slimane is 47, but looks at least a decade younger. He has the wide eyes of a deer and a preternaturally furrowed brow and bears a striking resemblance to the young Yves Saint Laurent. In 2012, after half a decade focusing on an acclaimed photography career (he photographed Lady Gaga's Fame Monster album art, and now shoots the advertising campaigns for Saint Laurent, among other assignments), Slimane returned to fashion as creative director of Saint Laurent, replacing Stefano Pilati, who replaced Tom Ford, who replaced Elbaz and Slimane.

But no one has ever designed Yves Saint Laurent haute couture, besides Yves Saint Laurent. Many saw it as the closest fashion got to art. In 1983, Saint Laurent was the first living fashion designer to be honoured with a retrospective at New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art. Designer ready-to-wear is, arguably, his most lasting contribution to the cannon of contemporary fashion – but Saint Laurent's heart and soul were in haute couture – he described his collections as "a love story between couture and me".

It was in couture that he really rang the changes. His turtlenecks and duffle coats, his leather jackets and transparent blouses, were all haute couture – the first time such garments appeared as high fashion. His tuxedos were the first trousers for women to be proposed not as mannish or practical, but elegant, even sexy. He created collections inspired by Africa and Morocco, and by neo-1940s styles worn by Saint Laurent's friends like Paloma Picasso and the drag queens in Andy Warhol's Factory set. The latter, a collection presented in January 1971, was dubbed "truly hideous" by the International Herald Tribune, which saw it as a celebration of wartime styles (and social mores) that older journalists were eager to forget. Nevertheless, it proved enormously influential: the wrapped crepe dresses, squared shoulders and clumpy platform shoes established the stylistic template for a decade to come. Yves Saint Laurent's haute couture shifted both fashion and popular culture, changing the way women dressed, and how they were perceived.

And now, Slimane has taken up the mantle. Haute couture is seen as a dream proposition for designers – the most rarefied form of fashion, with thousands of man-hours of work packed into single garments. Couture allies a seemingly bottomless pit of money (it can't be sewn on a shoestring, and makes no profit) with the limitless technical abilities of the best craftspeople in the world. Without commercial restraint, creativity can flourish. The clothes are bought by a tiny clientele: between 300 and 1,000 women worldwide, "the happy few", as Bruno Pavlovsky, president of fashion for the house of Chanel, once put it to me. They are passionate followers of fashion, willing to pay whatever it costs for something truly exceptional.

When Saint Laurent retired, he took pains to thank François-Henri Pinault, > CEO of the luxury conglomerate Kering, then PPR, which owns Yves Saint Laurent, "for believing as I do that this couture house's haute couture must stop with my departure". Prior to that, Pierre Bergé, Saint Laurent's former business partner and lover, had declared: "It is nonsense to carry on [couture] without him. Look at Chanel without Mademoiselle Chanel, and Dior without Christian Dior. It is more than nonsense. It has no integrity. It is a sham." Paradoxically, Bergé is a staunch supporter of Slimane.

There are a few major differences between Yves Saint Laurent's haute couture and that now being relaunched under his name. The house will not show during Paris's couture fashion weeks in January and July, eschewing the practice of introducing fresh ideas to be judged alongside contemporaries. Exactly how, and if, the collections will be presented, remains hazy. Its business model, even for the zero-profit world of haute couture, is also odd. A house executive – unnamed – has said that "Hedi Slimane decides these [couture] orders case by case. Unlike a couture collection, this is an even more exclusive definition."

Exclusive, or excluding? Because although haute couture is exclusive, it's open to anyone with enough money. By contrast, as a Saint Laurent communique issued earlier this month states, ateliers will "produce commissioned handmade pieces for movie stars and musicians. Hedi [Slimane] determines which of these pieces will carry the atelier's hand-sewn couture label."

But why call it haute couture, when that name comes loaded with baggage – especially at Yves Saint Laurent, and particularly under Slimane? What Slimane has done at Saint Laurent has polarised the fashion industry. He has honed an aesthetic, but in contrast with his work at Dior Homme, it's not identifiable through the actual clothes but the manner in which they are put together.

The silhouette isn't new; neither are the garments. Saint Laurent collections today are composed of leather jackets and tight jeans, laddered hosiery and short dresses. In direct opposition to the "exclusion" of his haute couture, Slimane's Saint Laurent appeals to the lowest common denominator. The clothes have been compared to those found in charity shops, or in Topshop. You could argue – as Saint Laurent frequently does –that this is all a part of its heritage. Saint Laurent himself once said he wanted "to introduce the whole sense of freedom one sees in the street into high fashion; to give couture the same provocative and arrogant look as punk". That chimes with Slimane's aesthetic and approach. "But," Saint Laurent added, "of course with luxury and dignity and style." Something shredded tights do not express.

I have further issues with much of this being presented in Saint Laurent's name. "It pains me physically to see a woman victimised, rendered pathetic, by fashion," said Saint Laurent in the introduction to the 1983 Met retrospective catalogue. I can't help think of that when considering Slimane's work. Groupie is a term bandied about in relation to his slashed tights and aggressively short dresses, tugged to expose legs and breasts. There's a brutality to them that makes their wearers look violated. They're unsettling but they don't feel provocative, transgressive, or progressive. Perhaps repetition has deadened their impact: Since the first, Slimane's collections have all trod similar ground.

Fashion critics are kept at arm's length, preferably further, in the new Saint Laurent. Slimane has, it seems, an aggressive antipathy towards any critical discussion of his garments. He seldom talks to the press backstage after his fashion shows, unlike most designers. If he does, it is off the record.

But I'm fascinated by Saint Laurent's financial success, by the glossy stores filled with handbags and T-shirts and leather jackets that look so much like so many others and are being voraciously purchased. It's a magic formula. In Kering's first-half financial report for 2015, released in July, Saint Laurent's turnover posted an increase of 24.3% year on year. The year's revenue to date – €443.1m (£309m) – is close to what Saint Laurent recorded for 2012's entire financial year. That was the year Slimane was appointed creative director, but the year before his clothes went on sale. He has doubled the house's turnover and sales show no sign of abating.

In 2012, Bergé denounced contemporary fashion, as a whole: "It is all a question of money and marketing. We never talk about talent – it's not the point. We only talk about sales. Yves Saint Laurent would have hated that." I tend to agree.

The house of Yves Saint Laurent is seen as both fashion's holy grail and its poisoned chalice. What an archive to mine – but what a name to live up to. That's the crux of my issue with Slimane's designs ready to wear, and haute couture alike. He isn't designing clothes under his own name – he could do whatever he wants there. He is designing for Yves Saint Laurent. That name represents something to me, and as part of a larger fashion dialogue. It represents a certain approach to clothing but it also touches on wider themes – gender, sexuality, culture – of which great fashion is always a fundamental part. Yves Saint Laurent represents a legacy. That is valuable, and it still means something to people who care about fashion over and above the money it makes, or indeed the label it bears.

I think Hedi Slimane is a very good designer. But right now, I don't think he is designing very good clothes. That's confusing, and frustrating, given the trajectory of his work at Dior Homme. Here, he isn't experimenting with shapes and silhouettes, trying to push fashion someplace new. It's formulaic and trite – antithetical to Yves Saint Laurent. It's like someone painting bad paintings and signing them Picasso – art critics would be livid. That's why I care about what Hedi Slimane does at Saint Laurent. And why I can't bear to see it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments