Graphic designer Peter Saville still rocks the fashion world

Saville's Factory work seismically shifted popular culture and the graphics he devised have been ripped off on every level

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Fashion finds it difficult to get over Peter Saville. References abound to his work, past and present. His aesthetic stamp chimes constantly with fashion's offerings. That's because Saville isn't just fashionable. His work is a style unto itself. He's the original. In Factory cataloguing lingo, Saville would be FAC-0.

Maybe that's because Saville's aesthetic imprint is vast. His Factory work seismically shifted popular culture, the graphics he devised have been ripped off on every level – especially in fashion.

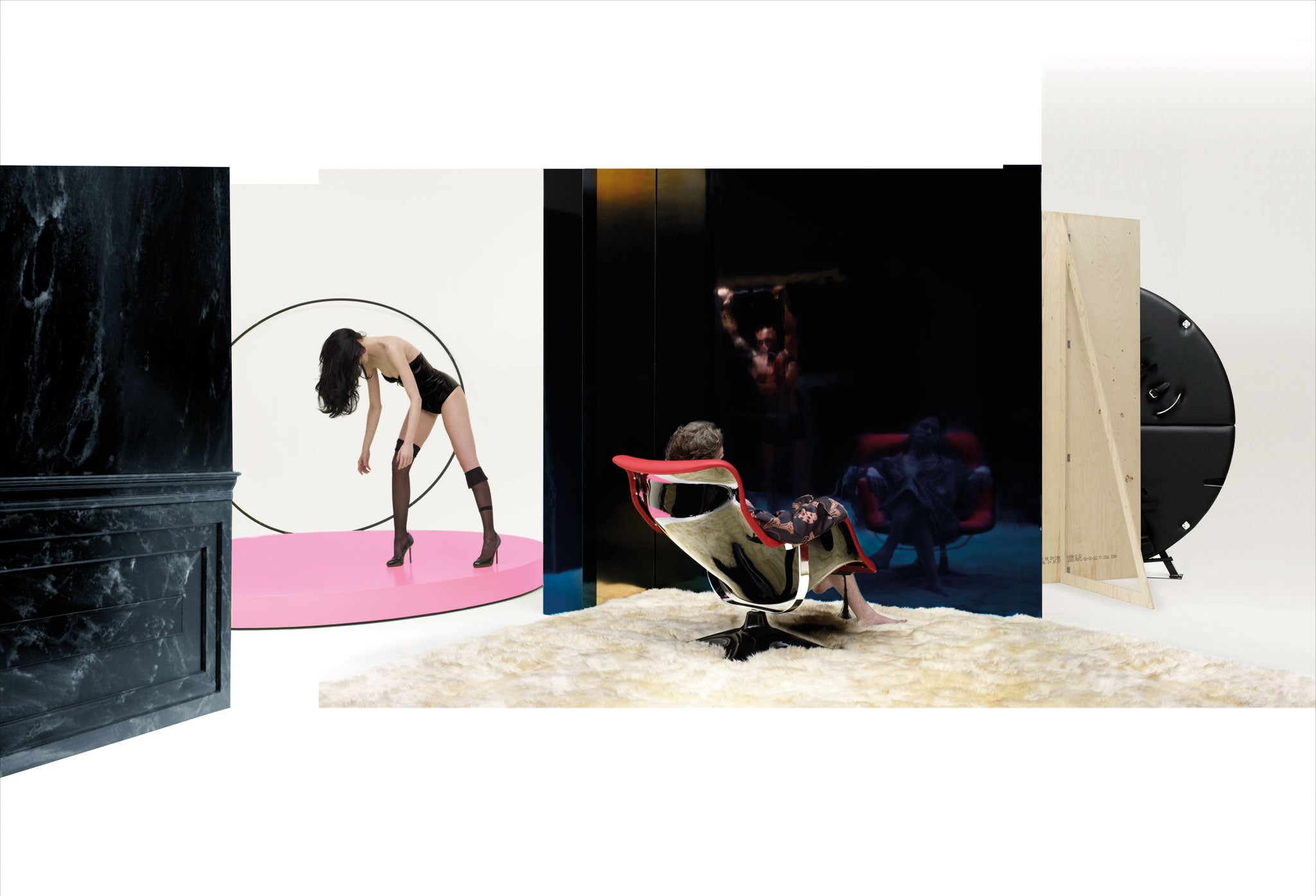

Saville doesn't mind that, though. He's been involved in fashion for years, working with Nick Knight on ground-breaking catalogues for Yohji Yamamoto which, like his album covers, became design fetish objects. The Yamamoto catalogues were supposed, ostensibly, to show clothing to sell clothing. It did the latter often by eschewing the former.

Even before Saville began working with fashion, he was fascinated with it. "From back when I was at college, I was always more interested in the other disciplines that were going on at art school than the one I was doing," he says. "Graphic design was a way of communicating something about the things I did find more interesting. I always found architecture, fashion, product design and furniture more interesting."

That fluidity of medium has become a way of working for many – fashion designers direct films, architects create clothes. Saville pioneered it. "Over the past 25 years, we've moved closer and closer to a common ground between these disciplines," he comments. "There is very much a converged aesthetic now, and a converged audience." Does Saville realise the fundamental role he played, by creating product design that became a product in itself? You can't really chart the influence and dispersion of Saville's ideas, because they're everywhere. Ubiquitous. Saville changed the lot.

Arguably, the designer who chimes the loudest with Saville's work is the Belgian, Raf Simons. In 2003, Simons delved into the archive of Factory Records, selecting works from Saville's back-catalogue to integrate into his winter collection. That show was called 'Closer' – after a Joy Division track, but also underlining that Simons was closer than ever before to Saville's universe. The collection was dedicated to Saville. Simons's work has been obsessed with youth culture, with the graphic details and decals of logo-ed band T-shirts, and with underground music scenes. In short, with Saville.

Ten years later, in summer 2013, Saville sat front-row at Raf Simons's spring 2014 show. It was an ode to youth, and music, and rave. The rave culture Saville's work so marked with its bright, two-dimensional colour and reappropriated imagery. Simons's models bounced out on hefty rubber-soled rave trainers, like chopped-up chunks of the Haçienda's interior. Saville seemed keen.

"Clothing is perhaps our most instant personal expression of individuality and sense of place. It can be an indicator of zeitgeist. I object to the commodification of spirit in the business of fashion." That's more Saville-ism. He evidently doesn't mean Simons. The spirit of Saville, and Simons, raves on.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments