How Donald Trump has affected the American fashion industry

Borders closing, travel bans, browbeaten allies – how is New York’s creative class doing, you ask? Not good, Not good at all

It begins with that most anodyne greeting: How are you? And then you see them flinch, or their shoulders slump. Heavy sigh. They struggle for an answer because here in the fashion world – populated by minorities, women, gays, immigrants, East Coast elites and all-around rebels – a lot of people are not fine. They are not OK. They are dismayed, angry, frightened. They do not like what they see happening in Washington. And they are processing it the way they know how: through fashion.

During four days of fall 2017 menswear shows, the runways have been filled with political commentary. Personal therapy. Catharsis through aesthetics. And a little bit of soothing balm.

How were the clothes? The clothes were fine. There was more upscale athleisure wear, all worn with fancy, retro sneakers. The suits are still snug and form-fitting, unless you are shopping at Boss or Joseph Abboud, where the trousers give a man more room and even have pleats. Some younger designers are toying with cropped pants – glorified culottes, really. And many of the clothes are artful – meaning that sometimes they look as though a designer has rifled through a vintage costume shop, as they did at Bode, or they were hand-splattered with paint, as at Stampd.

The menswear shows are still a young enterprise for the Council of Fashion Designers of America. Recognisable names such as Ralph Lauren do not mount runway shows. (Lauren, who recently severed ties with his CEO and is struggling to reorganise his business, presented his Purple Label by appointment.) But although Lauren still represents an enormous financial force in fashion, his menswear is classic. It is not leading the charge for change.

The more dynamic Thom Browne shows his clothes in Europe. (He’s the one to thank for those slim suits and all the trousers cropped to show manly ankles.) And many of the smaller brands struggle to find a distinctive voice. The biggest fashion news here was the decision by Raf Simons to bring his menswear line to New York for the first time. His oversize silhouettes and sharp tailoring immediately stood out.

But no matter how subversive, creative or extraordinary they might be, the clothes could not compete with the steady stream of news flashes coming from the Trump administration. Borders closing, travel bans, browbeaten allies, a conservative Supreme Court pick announced in the style of reality TV. How is New York’s creative class doing, you ask? Not good. Not good at all.

Abboud opened the season with a show marking his 30th year in fashion. He presented his collection in a decommissioned church. Taking a moment between a quick dress rehearsal and the resulting runway show of beefy men in black velvet, Abboud noted that he was showing the audience “his darker side”. The presentation was less a celebration of his professional longevity than a brooding commentary on life in this moment.

For some designers, protest and social commentary is a challenge. It is not what their work is about. For someone like Todd Snyder, who offered a sophisticated collection of track jackets, elegant knits and high-water trousers, his pre-show mood music was a call to arms: “Give Peace a Chance”. For others, politics melds naturally with the kind of clothes they have produced over many seasons. “I’m always influenced by what’s going on,” says designer Willy Chavarria, in an interview. “Because I'm Chicano and from California, I was raised around cholos and migrant workers, and my silhouettes, fabrics and drape always tie back to that subculture.”

“But it really came to light this last year,” he added. “The cultural divide really came to light.”

Chavarria’s collection was sketched out months ago as a commentary on oppression and the process of breaking free of it, but as he was sorting out how he’d present it to editors and retailers, he saw the Ava Duvernay documentary, 13th, which examines racism and the criminal justice system. It was a clarifying moment.

He used 13 models – non-professionals cast through social-media outreach and serendipity. (One guy worked at a restaurant near Chavarria’s office.) “Everyone was cast entirely based on swag,” he says.

His presentation opened with models standing in the cramped confines of a prison yard – a tight square surrounded by chain-link fencing and lighted from above with spotlights. Black-clad guards stood sentry. One by one, the models stepped out of the cage to walk confidently into the light and stand atop a platform. The soundtrack featured quotes from Malcolm X, Cesar Chavez, even RuPaul. The story was not simply about race, but also gender, sexual identity and ethnicity. Chavarria eloquently tapped into concerns roiling the nation, and he used the power of fashion to underscore our stubborn reliance on stereotypes and appearances, the way we segregate ourselves into opposing social tribes.

As designers used their presentations to work out frustrations, some were eloquent; some were blunt. A few just seemed to flail in frustration. And for some, it was deeply personal.

“I wanted to do as much as I could. With clothes, it feels a little bit silly, but it’s my life. It’s what I do,” says designer Robert Geller, who was born in Germany and graduated from the Rhode Island School of Design. He took his bows wearing a T-shirt inscribed with the word “immigrant”.

His models were dressed in his version of protective gear: purple camouflage overcoats, flame-red satin trousers, neoprene face masks.

Geller began working on the collection in July. “I was going to visit my family in Germany,” he said after his show. People there were reeling from the terrorist attack in Nice. “I came back and felt there was a sense of fear. And then in the summertime, Donald Trump became the nominee. It just kept getting worse and worse.”

He wanted the clothes to reflect that feeling of unrest. The face masks were his call to action – his call to protest.

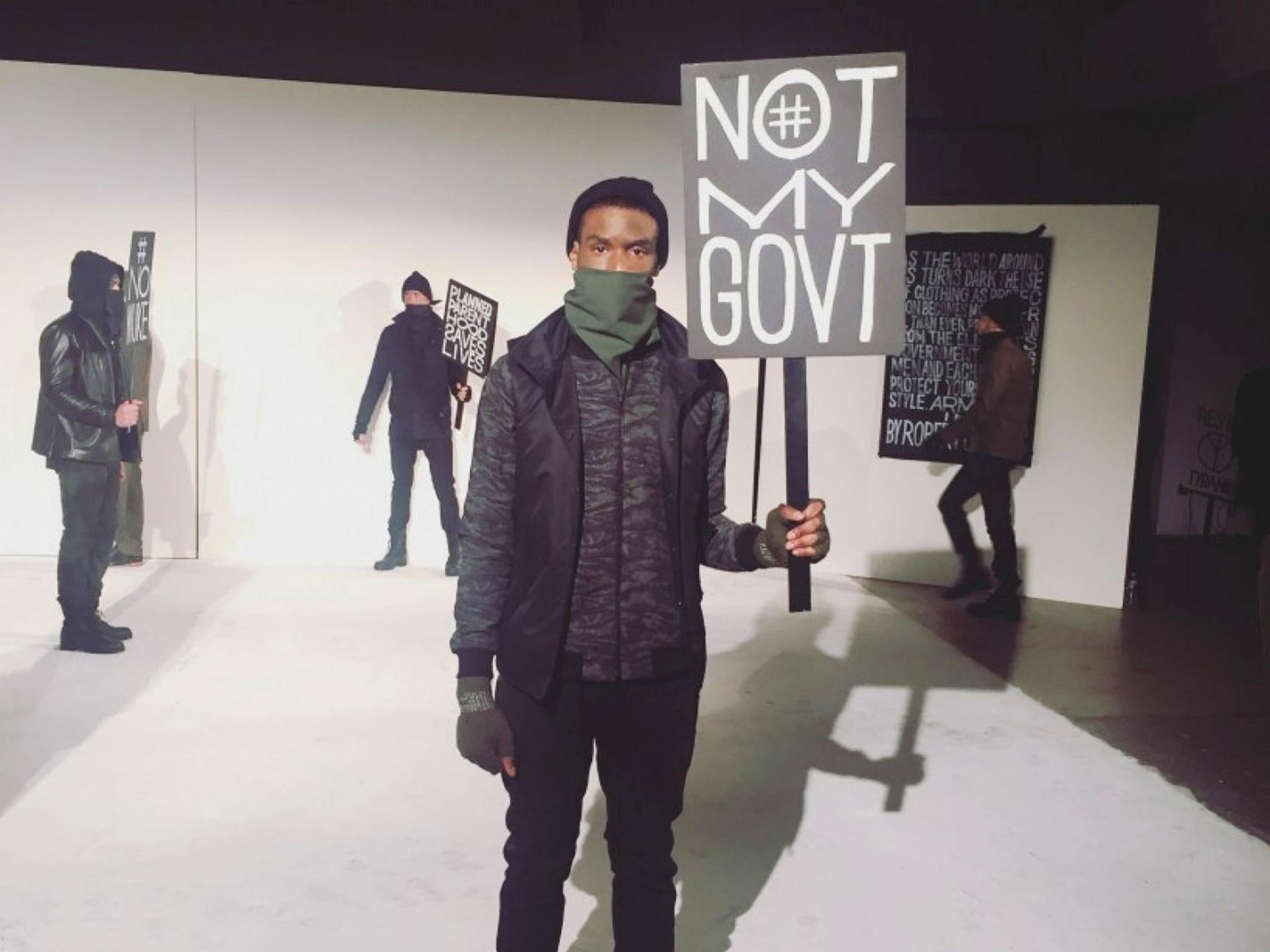

Robert James, too, wanted to incorporate the spirit of marches and defiance in his collection, called, appropriately enough, By Robert James. But he went a step too far, posting a kind of manifesto suggesting that his clothes were stylish protest attire, which gave his presentation of dark work coats and slim dungarees a whiff of cynical commercialism, which surely was not his goal.

Julian Woodhouse created a collection of shrunken sweats, bomber jackets and smart peacoats. There was no elaborate choreography, just models standing, and glaring – one in an expletive-adorned sweatshirt.

Daisuke Obana, the Japanese designer behind the brand N Hoolywood, took note of how homeless people improvise ways to stay warm and protect themselves while living on the street. Through a translator, he explained that he was inspired by their tenacity and creativity, and he used technical fabrics to mimic their sleeping bag coats, oversize denim jackets, heavy woollen trousers and too-big sweaters. He layered one garment atop another and another. His non-professional models, found in New York and New Jersey, paid homage to street people in a way that was unnerving in its verisimilitude.

But unlike so many passers-by, at he least he saw the homeless. He didn't walk past them with tunnel vision. He noticed how they made do with what they could find. He saw how they survived.

Certainly, not every designer felt compelled to turn the runway into a group therapy session. Brett Johnson mounted his first runway show with a warm, inviting collection inspired by Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains. Patrik Ervell looked to rave culture from the 1990s. (Save those throwaway clear-plastic rain ponchos. Ervell gave them a runway moment.) The once-earthy Ovadia & Sons embraced a hard-edged, street-infused tone.

And John Varvatos stayed true to his rock ‘n’ roll aesthetic, his models styled with blown-out hair, tight trousers, fitted jackets and a few leopard flourishes for good measure.

The Alabama-based Billy Reid also stayed true to his look of worn luxury. These are clothes meant to remain relevant from one year to the next – fashion that’s akin to a favourite chair. He presented the collection in a setting that evoked a coffee house concert with blues singer Cedric Burnside, country performers the Watson Twins and a poetry recitation by Tony-winning actor Alex Sharp.

It was cosy; it was personal. It was tonic. It was the work of a designer who spends his professional life crossing borders, from red state Alabama to deep-blue New York, from rural America to urban neighbourhoods. “I get to see the world from a lot of different perspectives,” Reid said, before his show. “I’m a Southerner, but I develop fabrics in France and Italy. It takes a whole world to get (a collection) together. We need that world.”

“Sometimes,” Reid says, “we lose sight of that”.

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks