Camp: Notes on Fashion review - A much-needed celebration of a profoundly queer, profoundly political aesthetic

The Costume Institute's exhibition is focused and cleverly thought out, offering an instructive journey through 300 years of camp culture, writes Clémence Michallon

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Three centuries ago, the French playwright Molière staged his play The Impostures of Scapin for the first time in Paris. Cultural history remembers the moment as the first known usage of the French words se camper – and the de facto birth of the camp aesthetic.

In the three-act comedy of intrigue, Scapin, a deceitful valet, convinces another servant to pose as a violent mercenary as part of a scheme to pocket a large sum of money. “Camp about on one leg,” Scapin tells him. “Put your hand on your hip. Wear a furious look. Strut about like a drama king.”

Camp flourished from there, growing out of Versailles into 18th-century queer subcultures before blossoming into the mainstream. The story of camp and its many iterations unfolds in the flamingo pink corridors of the Camp: Notes on Fashion exhibit, which gave its theme to the Met Gala earlier this week and opens to the public on 9 May at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.

The Costume Institute’s spring exhibition has become a long-awaited, headline-making affair. Last year’s Heavenly Bodies was especially spectacular, making history as the largest show ever put on by either the Met or the Costume Institute. But Camp: Notes on Fashion, based on Susan Sontag’s essay Notes on Camp, just might top 2018’s extravaganza. While it does feel smaller in size, this year’s show is also more focused and cleverly thought out, offering an instructive journey through 300 years of camp culture.

It all begins with a large pink wall with the word “CAMP” spelled out in luminous white letters. Then comes the first part of the exhibit, which takes visitors through a series of “deliberately claustrophobic” corridors, per Andrew Bolton, the Costume Institute’s head curator. The “whispering galleries” symbolise the secrecy and covertness that surrounded camp’s origins. As is customary of the Costume Institute’s shows, history, art and fashion interweave. A late 1980s Chanel outfit cohabits with an 18th-century portrait of Louis XIV. Jean-Paul Gaultier and Vivienne Westwood share the spotlight with Robert Mapplethorpe.

We’re taken from Molière’s camp to the camp of Christopher Isherwood, the author who in his 1954 novel The World in the Evening distinguished high camp (a sophisticated, baroque aesthetic) from low camp (“a swishy little boy with peroxided hair, dressed in a picture hat and a feather boa, pretending to be Marlene Dietrich”) – and you may or may not agree with Isherwood’s dichotomy, which has certainly been debated.

The male figure is ever-present, and the exhibition serves as a constant reminder that what we have come to think of as traditional masculinity is a recent, feeble concept, as there was once a time when the most powerful man in the land wore heels and luxurious garments on par with today’s couture gowns.

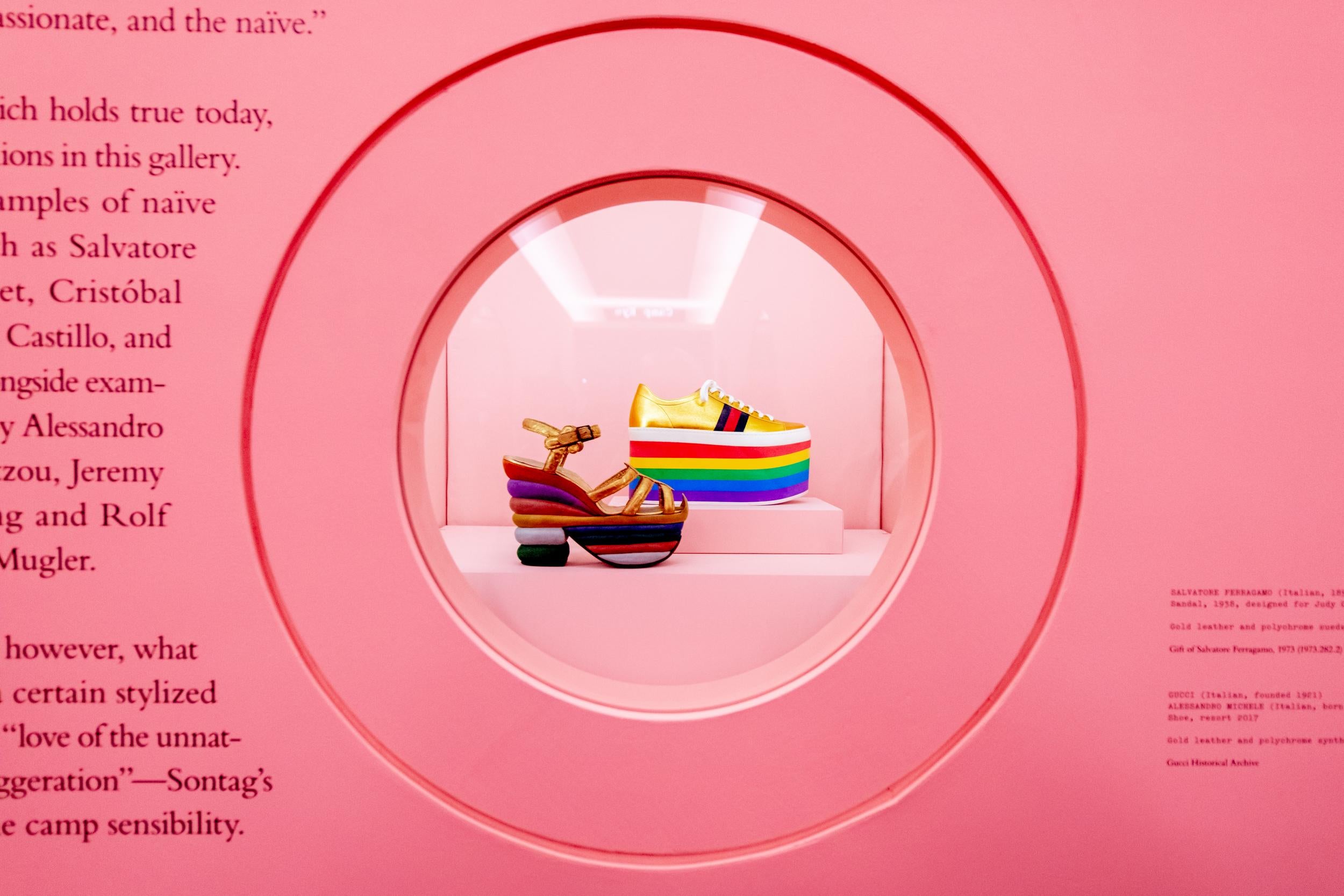

Speaking of couture – it is, of course, one of the driving forces behind the exhibit. Displayed behind glass panels are a tuxedo / gown hybrid by Gaultier, a pair of Erdem silk taffeta evening dresses (one blue, one pink) paying tribute to Fanny and Stella, two Victorian cross-dressers whose “drag wardrobe” was confiscated by the police in 1870, and an Oscar-Wilde-inspired wool ensemble from Gucci’s spring/summer 2017 runway. Gaultier’s famous sailor suit is reinvented in a 1997 disco version, complete with blue sequined trousers and a crop top. In a nearby display, a pink mannequin is wearing a sleeveless mini dress printed with Andy Warhol’s iconic Campbell’s tomato soup cans. Paul Poiret, Mary Katrantzou and Cristóbal Balenciaga all feature. You might also recognise the spectacular archive Thierry Mugler ensemble worn by Cardi B to the Grammys in February, with its embroidered beige bodysuit and its distinctive black silk velvet and pink silk satin dress, all preserved from the mid-1990s. This bountiful first half culminates with Susan Sontag’s essay, the draft of which is on display next to a photo of its author.

Sontag, says Bolton, was “the first writer to explore camp as a serious subject – one worthy of political and cultural analysis”. She was also, according to Met director Max Hollein, a frequent visitor of the museum on the Upper East Side of New York City. In her essay, Sontag defines camp as a “sensibility” – one that is “unmistakably modern, a variant of sophistication but hardly identical with it. Camp, she says, is “esoteric”; it attracts her “almost as strongly” as it offends her. As she bravely takes on the task of defining camp (many have said they have tried and failed to fully grasp the context), she pins it down as “one way of seeing the world as an aesthetic phenomenon”. “That way, the way of Camp,” she adds, “is not in terms of beauty, but in terms of the degree of artifice, of stylization.”

Perhaps most helpfully, and in an apparent admission that it is easier to see camp than it is to put it in words, Sontag provides a list of items that she sees as occurrences of camp, referencing Tiffany lamps, Scopitone films, the ballet Swan Lake, Bellini’s operas, “the old Flash Gordon comics”, “women’s clothes of the twenties (feather boas, fringed and beaded dresses, etc.)” and “stag movies seen without lust”. Movie criticism, she says, is “probably the greatest popularizer of camp taste today, because most people still go to the movies in a high-spirited and unpretentious way” (Sontag, clearly, did not live in 21st-century Williamsburg).

You see Sontag’s camp in full blossom in the second part of the exhibit – a spacious dark room in stark contrast with the first half’s purposefully cramped “whispering galleries”. The room, an “echo chamber”, per the exhibit, symbolises an “outing”. Camp is no longer secretive, no longer claustrophobic – and, as extravagant as it sounds, visitors can feel the physical effect of that liberation as the air around them becomes cooler and easier to breathe. Here, clothes are no longer restricted to ground level, but rather are spread out from floor to ceiling. In one display, Ashish’s sequined outfits sparkle with messages in bold letters, such as “You are much lovelier than you think” and “Fall in love and be more tender”. Björk’s iconic Marjan Pejoski swan dress, which she wore to the 2001 Oscars, is on display, as is Lady Gaga’s attention-grabbing faux-meat dress (the original was made of raw meat) from the 2010 MTV Video Music Awards. There are tuxes and medieval-inspired gowns and spectacular headpieces, and enough tulle to give Killing Eve‘s Villanelle a run for her money.

Camp: Notes on Fashion treats camp as an omnipresent force, one that is easy to spot but hard to confine within words. Camp is frivolous on the surface and profound by essence; it demands to be seen but refuses to be judged. It’s edgy and innocent, unapologetic and a certain kind of beautiful. Camp, as a voiceover reminds visitors, is at its core political and subversive. Herein lies the main hurdle the exhibit must overcome: people come to the Costume Institute to see beautiful things. Camp seems like the perfect vehicle for such a desire (and one does, in fact, marvel at Gaultier’s iconic sailor outfit, a Jeremy Scott spheric gown adorned with paper butterflies, a Ferragamo rainbow shoe created for Judy Garland, and so many other treasures). Camp refuses to be weighed down, yet reducing it to frivolity would be a mistake. Doing so would erase queer pain, and omit the risks people take every day walking the streets looking like they do and being who they are.

Camp happens, perhaps, when the barrier between someone’s true self and the rest of the world opens. Gucci creative director Alessandro Michele, whose designer house partnered with the Costume Institute for the exhibit, said at the press presentation of the exhibit that he was “very happy” when Anna Wintour (who chairs the Met Gala) and Bolton told him about this year’s theme over breakfast. It was “so close to my lifestyle”, he said in his native Italian. Camp, he added, is a “beautiful word”, because it teaches us in just a few letters how important it is to be free – to express ourselves through our clothing and, from a political standpoint, to be whoever you want to be. As a child, Michele said, he wanted to do things on his own terms and dress on his own terms, two desires that might be the foundational pillars of camp.

Bolton, who said he has been asked many times why the Costume Institute had chosen camp as this year’s theme, explained he has witnessed a “resurgence of camp, not just in fashion but in culture in general”. Camp, he said, tends to gain traction “during moments of social and political instability, when our society is deeply polarised”, owing to the fact that camp “reacts with and against the public opinion”.

Sontag, as Bolton pointed out, viewed camp as “a mode of enjoyment, of appreciation – not judgment”. “Camp taste is a kind of love, love for human nature,” she wrote. “It relishes, rather than judges, the little triumphs and awkward intensities of ‘character.’ [...] People who share this sensibility are not laughing at the thing they label as ‘a camp', they’re enjoying it. Camp is a tender feeling.”

Camp: Notes on Fashion shares this tenderness. The exhibit is entertaining and educative, and the attentive visitor will relish in the many sensibilities of camp. It’s a needed celebration, and well worth a detour by the Met’s polished steps.

Camp: Notes on Fashion opens at the Metropolitan Museum of Art on 9 May, continuing through 8 September, 2019.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments