Emma Stone preferring to be called Emily is about more than just a name

The actor has expressed a preference for ‘Emily’ rather than the acting moniker she was forced to adopt early in her career. Helen Coffey looks at why names are so important – and how they can fundamentally shape our identity

Sometimes, it feels like I’m living a double life. Not in any grandiose, dramatic way – there’s no secret agent, 007 glamour to any of it. It’s just that, almost by accident, I ended up with two names. There’s “Helen”: my professional self, a journalist who lived in London for over a decade. And then there’s “Lenni”: my off-the-clock self, who moved to a seaside town, loves smugly bragging about winter swimming, and inexplicably started writing songs on the ukulele for the first time in her thirties.

They are, of course, one and the same person. But they feel different – it’s like going between wearing a pair of dungarees and a formal trouser suit. Both items fit me just fine, but my physicality – the way I move through the world and my attitude towards it – subtly shifts when I’m wearing each one.

Anyone who has a given name and a sobriquet understands the strange binding of identity that’s inherent within a handful of letters. It’s why Emma Stone’s partiality to being called by her real name – Emily – is back in the media spotlight again. The Oscar-winning actor hasn’t made a big song and dance of it; she’s merely stated several times that, given the choice, she’d rather go by the name that feels more like her than the stage name she was forced to adopt at the start of her career (“Emily Stone” being already taken by another member of the Sag-Aftra actors’ union).

“I freaked out a couple of years ago,” Stone said in a recent interview with The Hollywood Reporter alongside her The Curse co-star Nathan Fiedler. "For some reason, I was like, ‘I can’t do it anymore. Just call me Emily.’” She added that if a fan addressed her as “Emily”, “that would be so nice. I would like to be Emily.”

We’re on opposite sides of the same coin. I was christened “Helen”: a perfectly fine, decent name that, regardless, never felt like me. When I got to university, I somehow developed the nickname “Lenni”, itself spawning a whole tranche of spin-offs (Lemon, Lemonhead, Lemony Snicket), and for the first time felt a real connection to the collection of syllables with which people identified me. “Helen” to me felt stuffy, uptight, reserved, judgemental – I was Helen Daniels, the boring, matriarch grandmother from Neighbours. “Lenni”, by contrast, felt young, carefree, spontaneous, fun. That was the person I wanted to be.

Once I moved to the capital to begin my career, though, it felt a little, well… silly, to introduce myself as such. Childish, even (and I so desperately wanted to finally feel like an adult). People would ask questions about the provenance and I’d have to explain – so I uncomfortably reverted back, feeling too embarrassed to do otherwise.

It wasn’t until 13 years later, when I moved to a new town where no one knew me, that I reclaimed my epithet by chance. Unbeknown to me, when I’d first set up WhatsApp, I’d saved “Lenni” as my username, which then pops up as your moniker for anyone who doesn’t have your number saved. As I joined new group chats to make friends, people would associate me with my chosen alias. It felt organic, rather than forced, and I was delighted. Now, when someone learns my real name, they’re often weirdly shocked; they can’t quite get their head around this other version of me out in the world, fundamentally the same yet intangibly altered.

The same identity crisis can be true for people with audibly foreign, rather than Anglicised names. A friend of mine switches between introducing themselves with their full Arabic name – which will often prompt further questions, requests for how to spell it, interest in where they’re “really” from – and giving an easy, shortened version instead. It mainly depends on whether they like the person in question enough to think they’re worth the time investment of providing the “real” name.

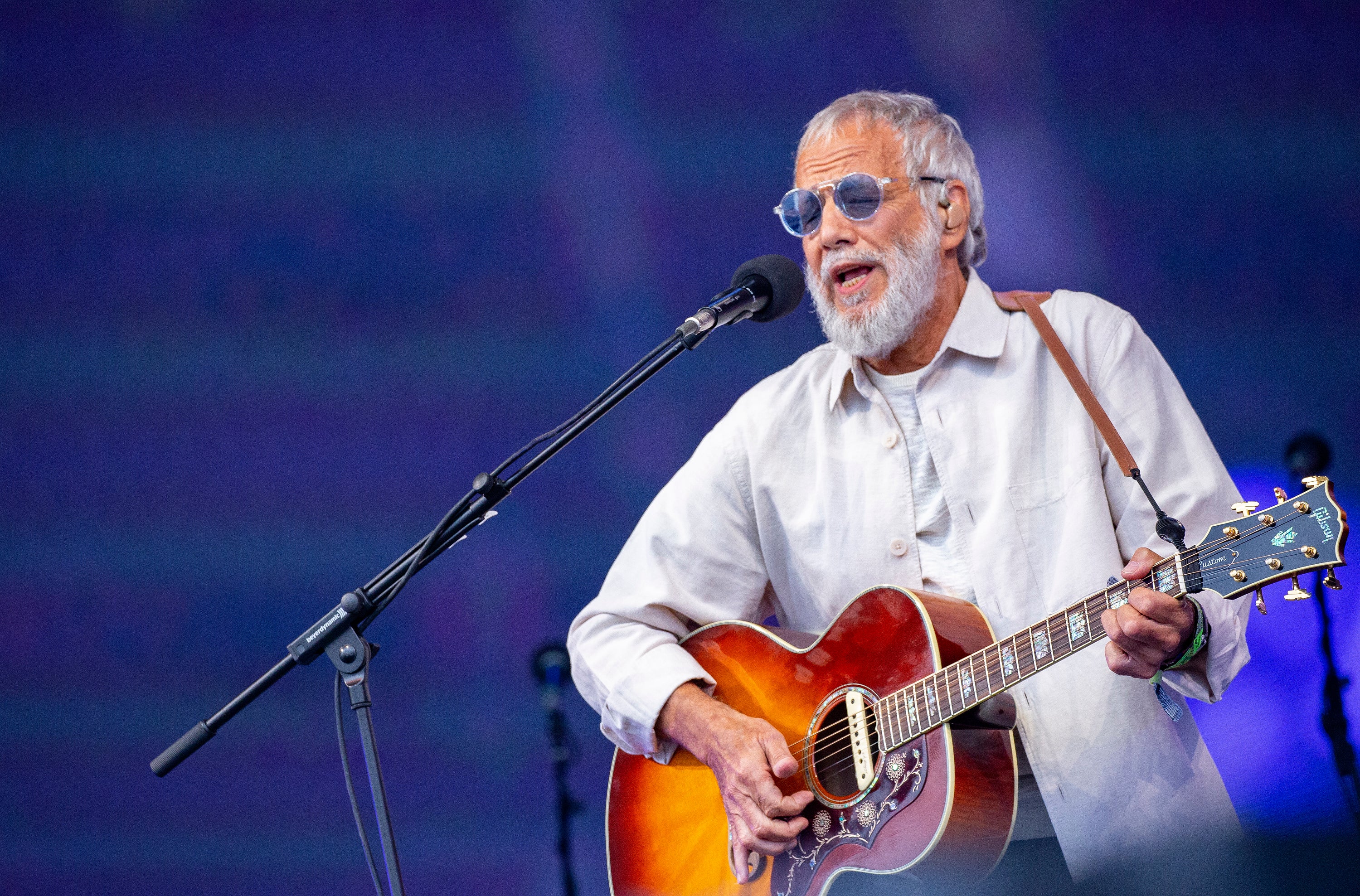

Then there are those who choose another handle to illustrate a significant new beginning – representing something of a ritual rebirth. The singer Cat Stevens (itself a pseudonym as he was born Steven Demetre Georgiou) becoming Yusuf Islam after converting to Islam, for example; a friend’s sister who decided to go by her middle name after coming out of rehab and getting clean. And, perhaps most symbolically, the decision of many trans people to pick a new name to represent the gender they identify with. Think actor Elliot Page choosing a name he’d always liked thanks to the film ET’s main character, or comedian Suzy Izzard selecting the moniker she’d wanted to give herself since she was 10 years old.

A name under these circumstances is so much more than just an arbitrary scramble of letters. It becomes a defining characteristic, holding within it the power for someone to rewrite their story and become the person they’ve always longed to be (or already felt they were). It’s why “deadnaming” a trans person – where you call them by their birth instead of their chosen name after transitioning – can be so deeply hurtful, especially if done intentionally.

A name under these circumstances is so much more than just an arbitrary scramble of letters

“Many years ago, when I was contemplating suicide, I was planning to have a note in my pocket at the time of my death and several other notes in my home which would state my name, preferred gender pronouns and that I should be referred to as a woman in my death,” the actor Laverne Cox once tweeted in response to a 2018 report highlighting how US police forces were consistently misgendering and deadnaming trans murder victims. “My note would be clear that I should be referred to as Laverne Cox only, not any other name.”

Even under far less dramatic and damaging circumstances, getting someone’s preferred name correct isn’t difficult. Why not just do it?

In the end, I’m not sure I agree with Shakespeare on this one. What’s in a name? Quite a lot actually. A Stone by any other name may still have won two Oscars – but if Emily’s what she likes, Emily’s what she should get.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments