Should I give up Diet Coke? With aspartame under suspicion, an addict speaks

Katie Rosseinsky’s consumption is not on the level of Donald Trump’s, but she’s still concerned about its possible links to cancer. She explores the history of diet drinks, why more women drink them, and whether she should stop

Here’s a confession. When I hear the crackle of a pull tab as a drinks can is opened, followed by that rush of carbonated fizz, it kickstarts a conditioned response. Almost immediately, I start to think about how much better my current situation would be if I was sipping on a Diet Coke. It’s embarrassing, but over the years I’ve come to terms with the fact that I’m basically the Pavlov’s dog of Big Soda.

My Diet Coke consumption has never come close to reaching the level achieved by Donald Trump (who reportedly gets through 12 cans in 24 hours) or the late Karl Lagerfeld (whose daily regime included 10 of them, according to the diet guide he released in 2004). But it’s habitual enough that when a certain news alert pinged onto my phone screen last month, it made me shudder.

The chill-inducing headline in question? The revelation that the World Health Organisation’s International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) was preparing to label aspartame as “possibly carcinogenic to humans”, also known as category 2B. Aspartame is, of course, the artificial sweetener used in my beloved DC, along with countless other sugar-free fizzy drinks and low-calorie food options.

The International Sweeteners Association has already taken issue with the report, noting that the IARC is “not a food safety body” and claiming that its review is “not scientifically comprehensive”. And the potential WHO ruling, it should be noted, doesn’t consider how much of a substance a person can consume safely; that is the job of another WHO group, known as JECFA (the Joint Expert Committee on Food Additives, in partnership with the UN).

Confused yet? It has always been difficult for consumers to get a handle on aspartame’s risk. The sweetener has been around since 1965, when the American chemist James Schlatter accidentally discovered it while attempting to formulate an anti-ulcer drug. After combining two naturally occurring amino acids, aspartic acid and phenylalanine, Schlatter, a health and safety officer’s worst nightmare, stuck his finger into the mixture and licked it.

He might have bypassed basic lab rules (and basic common sense), but he’d stumbled across a new low-calorie sweetener in the process. Aspartame is “approximately 180 to 200 times sweeter than sucrose”, a naturally occurring sugar, explains Dr Terun Desai, senior lecturer and researcher in exercise physiology and clinical nutrition at the University of Hertfordshire. So, you need “a lot less product to achieve that sweet taste. And obviously, from a manufacturing point of view, if you need less of something, then that’s more efficient.”

But since its discovery, aspartame has been beset by controversy. It received approval from the US Food and Drug Administration (the FDA) in 1974, and initially, Desai says, researchers “started looking at aspartame as a product that might potentially have health-promoting benefits”. Their early work, he explains, was “primarily looking for its benefits on cardio-metabolic health” – exploring its effect on the heart, blood, and blood vessels. But then some scientists argued that the studies into its overall effects “weren’t as rigorous as they could have been, so the FDA removed its approval” in 1980.

[Diet Coke] has only reinforced the dichotomy between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ [products], perpetuating the idea that certain foods or ingredients are inherently virtuous or sinful

The following year, they “reapproved it again, having done more [research]”. Soon after, Coca-Cola launched its silver-canned Diet spin-off. Ever since, there have been question marks hanging over the potential health implications. A report from the Ramazzini Institute linked cancers in mice and rats to aspartame consumption, and a French study of around 100,000 adults last year suggested that people who consumed large amounts of artificial sweeteners had a slightly higher risk of cancer. Confusingly, though, there is also plenty of research out there stating that there is no link between artificial sweeteners and cancer (and the deleterious impact of sugar itself is also very well documented).

Against this backdrop of ongoing uncertainty, why are diet-drink diehards like myself so keen to keep drinking? As well as being super-sweet, aspartame’s calorific value is pretty negligible. One can of Diet Coke contains about one calorie, a fact that has been seared into my consciousness in the brand’s wiggly cursive font since adolescence. Did my enthusiasm for the drink precede this knowledge? I’d like to tell myself so, but I’d probably be lying.

Documenting her attempts to kick her Diet Coke habit in The Guardian, the writer Sirin Kale described it as “diet culture in a can”. It’s an assessment I’m inclined to agree with. As a teenager in the mid and late Noughties, I’m not sure I’d have gravitated towards diet drinks quite so zealously if they weren’t whispered about as a sure-fire route to that era’s most aspirational quality – thinness. Another caveat: earlier this year, the WHO released new guidelines recommending against the use of sweeteners to control weight, as there is no evidence of long-term benefit. But when cultural messaging and urban myth have got under your skin, it’s hard to shake them off.

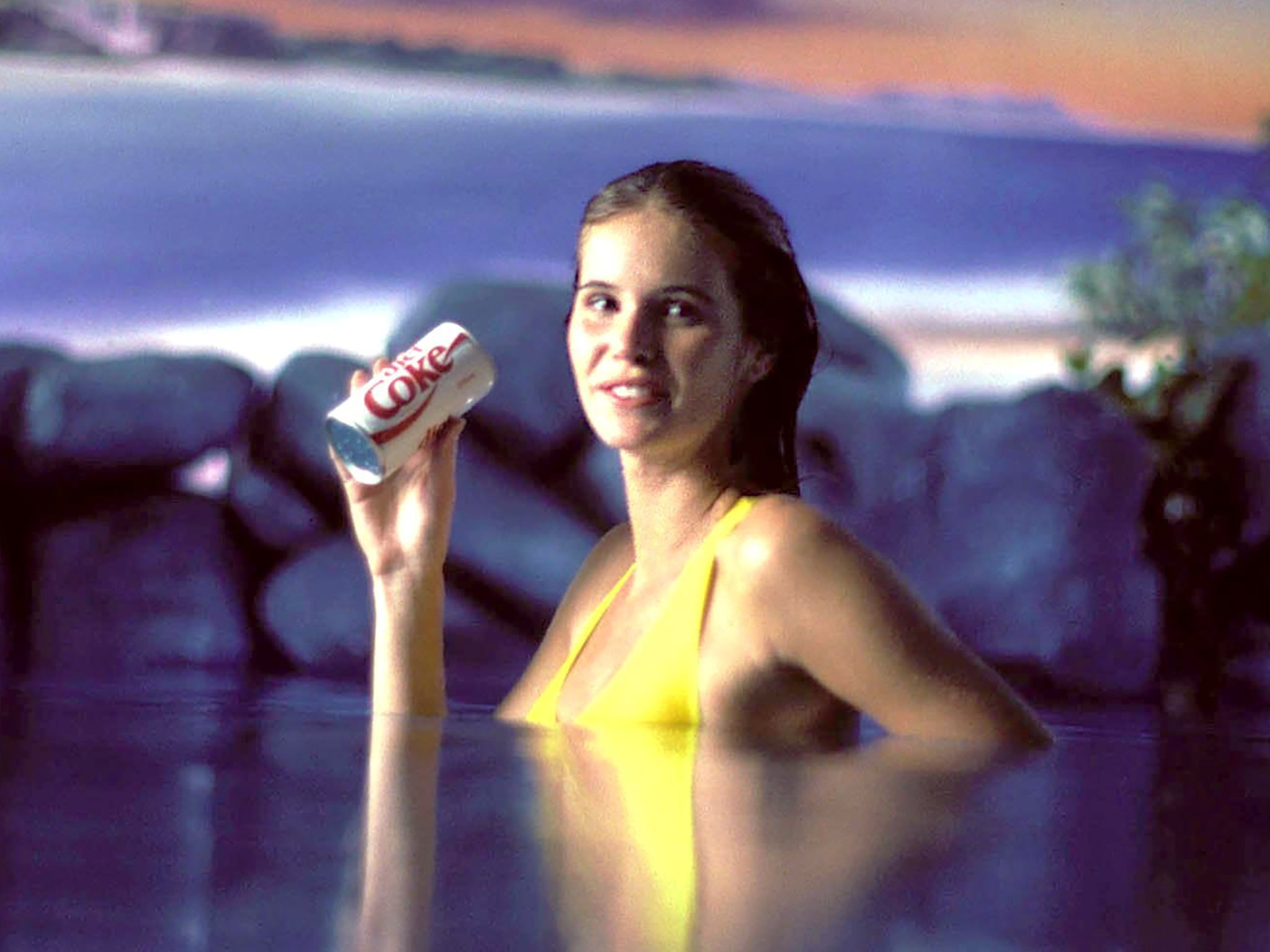

Before aspartame, there was saccharin (and the less well-known cyclamate). When diet sodas first launched in the late Fifties and early Sixties, the link with thinness was more explicit – and more explicitly tied up in old-fashioned ideas of femininity, seen through a male gaze. In 1964, Diet Pepsi launched with a tagline that was both convoluted and spectacularly creepy. “The girls that girl-watchers watch drink Diet Pepsi,” the ads claimed – a bottle of this stuff, they suggested, would make you worthy of being leered at in the street by passing men. The early marketing for Tab, Coca-Cola’s debut foray into the diet drinks world, wasn’t any better. “Stay in his mind with a shape he can’t forget!” the product promised, claiming that drinking Tab would turn you into... wait for it... “a mindsticker”.

The end goal “wasn’t really about health per se, but about beauty and appearances”, says Pierre Chandon, professor of marketing at the INSEAD business school in Fontainebleau, France. These drinks, the ads seemed to be saying, offered indulgence in a limited form. You could have something sweet, and still be slim enough to be deemed worthy of attracting male attention.

Indeed, “diet soft drinks historically promoted the idea that a woman could ‘have it all’, enjoying the taste of a sweet beverage while avoiding all of the negative consequences associated with sugar consumption,” notes Kirsty Minns, executive creative director at branding agency Mother Design. “This approach has only reinforced the dichotomy between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ [products], perpetuating the idea that certain foods or ingredients are inherently virtuous or sinful,” she adds. “Think of the term ‘full-fat coke’” – a nickname laden with value judgements.

Because Tab was so blatantly aimed at women, Coca-Cola was concerned that male customers wouldn’t pick up a can of this (quote unquote) girly drink. Enter Diet Coke. Yes, ironically, this second low-cal offering was initially intended as a way of getting men to get on the diet-drink bandwagon: the early advertising featured blokes at sports games, blokes fishing, blokes joking around at the swimming pool. By the end of 1983, it was America’s best-selling diet soft drink, but the d-word was apparently still putting men off. In a report in The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, a Coke source claimed that “diet” was still considered to be “a four-letter word” for men, at least the younger ones.

It was time for Diet Coke to lean into its female demographic – which they famously did in 1994, with the introduction of the first notorious “Diet Coke break” ad. “[They] were kind of risqué for the category,” notes Chandon, “by showing women ogling an attractive man drinking Diet Coke. Although now the man was drinking the soda, it was still clearly targeted at women” – thirsty ones, you could say. It flipped the script on the old-school drink ad: this was a game-changing clip that was unabashedly all about the female gaze.

But how empowering can an advert encouraging us to buy into a megabrand (especially one that’s rooted in strict beauty standards) ever really be? In pop culture in the late Nineties and the Noughties, a procession of skinny celebrities were papped clutching their diet drinks; Diet Coke also cropped up through product placement in teen movies like Clueless and John Tucker Must Die (perhaps because revenge, like Diet Coke, is best served cold?)

Later partnerships with figures like Marc Jacobs, Jean-Paul Gaultier and Lagerfeld (notorious for his fatphobic comments) “sought to reinforce the drinks icon’s connection with fashion – a sector long muddied by accusations of peddling unhealthy beauty standards and ideals”, Minns notes. And now that the Diet Coke break ads have been retired, the marketing undercurrent has, “whether intentional or not”, been “one that feeds on diet culture and its associated unhealthy beauty ideals”, she adds: recent ads with taglines like “Regret nothing” and “Because I can” have “arguably played into the hands of the diet mindset”.

In a wellness-focused world, Diet Coke might not quite have the cultural cachet it once had (the Trump link probably didn’t help, either). The way we think about healthy eating and drinking has changed, Chandon says. Once, he explains, brands could claim to be healthy “because of the presence of ‘good’, like proteins, or the absence of ‘bad’, like salt, sugar or fat” – diet drinks took the latter approach. But “brands now claim to be healthy in a totally different way” – the trend is “for foods that are healthy by nature rather than healthy by nutrition” (making artificial ingredients, like sweeteners, seem less attractive by default).

Will the scare-inducing headlines around aspartame cause us to turn our backs on diet drinks for good? Minns is pragmatic. “Let’s be honest here,” she says. “The fact is that consumer habits are inherently difficult to influence, let alone change.” In 2015, she notes, the WHO put red meat onto the 2B watchlist of possible carcinogens. “If the meat industry is anything to go by,” she says, “the drinks sector is likely to experience a drop-off in sales in the immediate weeks that follow the WHO report, but the chances are that the diehard diet-drinks loyalists will throw caution to the wind and return to their usual drinking habits, if they ever abandon them in the first place.” Another confession: I got through a can of Diet Coke or two while writing this feature.

The aspartame risk needs to be considered in context, too. Other substances in category 2B include aloe vera, nickel, caffeic acid (found in coffee), pickled vegetables and coconut oil products. As Desai puts it, the sweetener has “only gone up to a possible carcinogen, rather than a probable cause”. The semantics are important – and so is the aforementioned fact that the WHO ruling doesn’t take the amount consumed into account. “The amount that is considered acceptable for daily intake is relative to body weight – it’s 50 milligrams per kilo per day in the US, and according to the Food Standards Agency in this country, it’s 40.” If you assume that the average adult male weighs around 85kg, he notes, that “equates to about 17 cans per day” before you reach the threshold. For women, it’s 14 cans. In a risk assessment released on 14 July, JECFA reaffirmed that 40mg per kilo daily limit as the “acceptable daily intake”.

I suddenly feel a little bit less panicked about my own imminent demise. The JECFA ruling will hopefully give diet-drink connoisseurs like me enough information to make an informed decision about whether we keep sipping or not. But the potential damage wrought by the diet culture that got me hooked in the first place? That’s much, much harder to quantify.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks