Did Japanese workers really get their symbols mixed up and display Santa on a crucifix?

Tim Willis reports on the urban myth that refuses to die

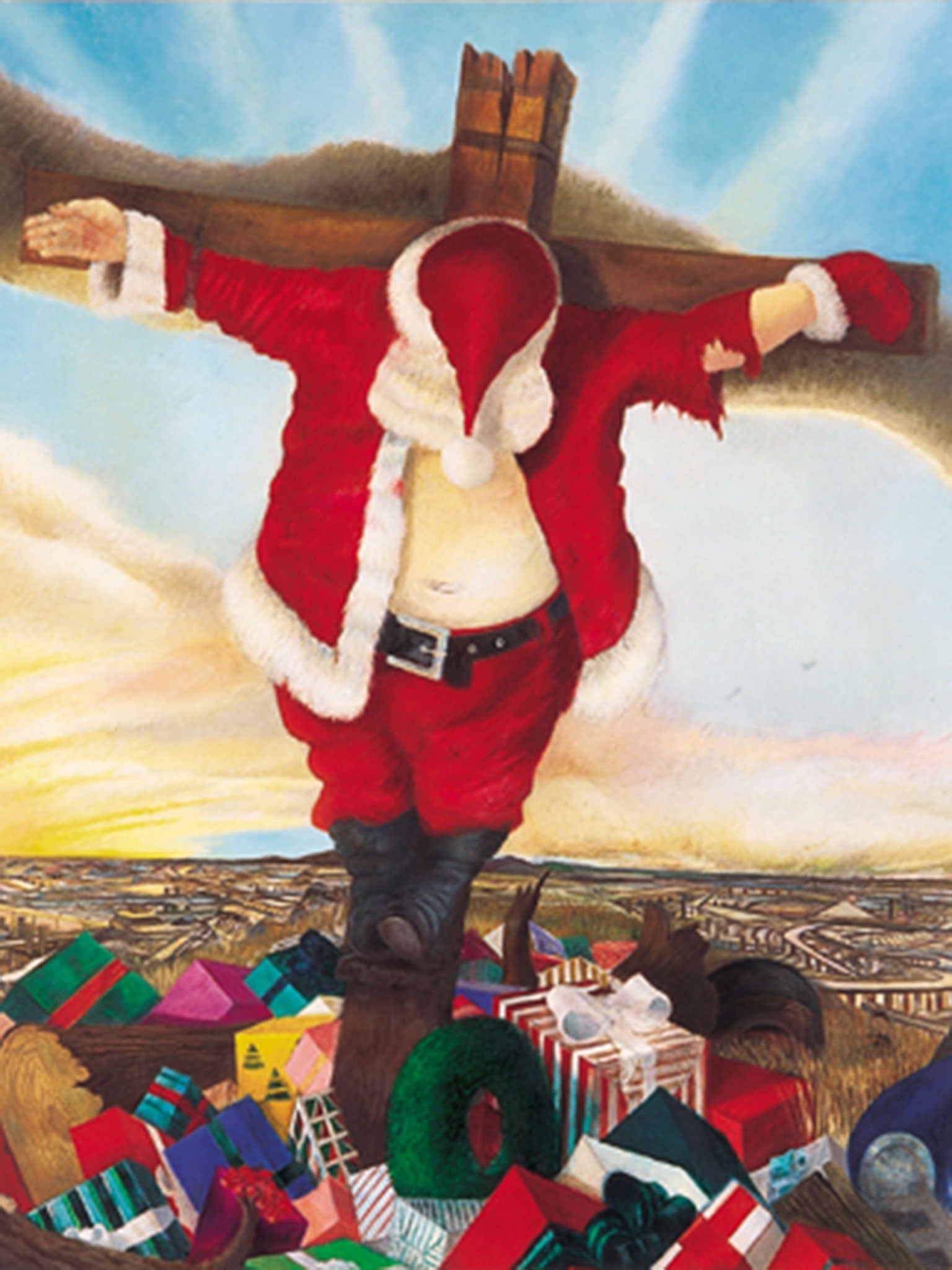

If you type "crucified Santa" into Google Images, you'll see that various idiots have mocked up pictures of the jolly old soul nailed to a cross; or gone one better, donning Father Christmas outfits and posing like the dying Christ on crosses of their own; all in tribute to one of the world's great cultural confusions.

The story goes that, some time after the American occupation of post-war Japan, its inhabitants were first exposed to the non-religious aspects of Christmas – elves, grottoes, sleigh bells and the rest – and came to understand that the fat man from the North Pole had something to do with the birth of Jesus (best remembered in those parts not for his humble birth but for his gruesome end).

Wanting to join in the spirit of the thing and demonstrate their modern, "Western" credentials, Japanese shopkeepers saw an opportunity to stimulate sales. And so, with more zeal than scholarship, the window dresser at one of the main department stores produced his centrepiece: a life-size effigy of a smiling "Father Kurisumasu" – complete with white beard, red tunic, shiny belt and boots – attached to a facsimile of Our Lord's final instrument of torture…

Unfortunately, the story's too good to check – because it never happened. Such misunderstandings have occurred in other places at other times. (When the Cuzco Indians of Peru were converted to Catholicism, for instance, they mixed up angels and conquistadores, and in their paintings equipped the heavenly host with muskets instead of bugles.) But the Japanese Passion of Santa Claus is an urban myth.

Although The Washington Post reported it in 1995 and The Economist in 1993, there are no photographs or first-person recollections. The source has been at best what modern folklorists call a "foaf", or "friend of a friend". The incident has been variously dated to the 1940s, 1960s and 1980s – in these publications and others – and located in both Tokyo and Kyoto.

According to Snopes, the myth-busting website, accounts first surfaced in the early 1990s, and reflected growing anxiety among Americans about the USA's position as the world's economic superpower: the Japanese electronics and motor industries were outstripping theirs; and Japanese investment in the New York property market – where they had acquired such landmarks as the Rockefeller Centre – was causing the kind of resentment that some Londoners bear wealthy Chinese today.

On the other hand, that doesn't mean that the story is entirely false. As the poet said, truth is beauty, beauty truth. And like all great "contemporary legends" – as those folklorists call them – this one exquisitely captures the fact (or fear) that the Japanese had both adapted and adopted Western consumerism to impressive effect and profit without really understanding or espousing the underlying values. And clearly, some of them had a different take on physical cruelty and suffering, as any manga fan would tell you.

Similar interpretations can be applied to such old favourites as "the vanishing hitch-hiker" and new ones such as the "Chinese kidney-harvesting kidnap". The first, which dates back to the Middle Ages, reappeared on inter-state highways after Pearl Harbor and spoke to the dislocation and isolation then felt by so many Americans. (It had another run in the 1970s, as stories of serial killers preying on drifters gained currency.) The second is fuelled by fears of people-traffickers, and a commercial market in donated organs. But what gives the Japanese tale the edge is that you can almost, just, possibly, imagine it.

After all, look how the Japanese have overlaid their imaginations on our own rites and icons. Never mind the genuine Kurisumasu cards featuring Mary on a broomstick and a spooky Santa. (Some mix-up with Halloween?) What about those college-style sweatshirts with words apparently chosen at random: "Precise Dwarf Bravery", for example. What about the Japanese rockabilly scene, which has somehow absorbed line- and break-dancing into its bizarre car-park dance-offs? They act as a kind of post-modern critique of our own culture.

Which is presumably what the New York artist Robert Cenedella intended with a picture he exhibited in December 1997, to the outrage of some religious groups. As a commentary on how the Christian message of the nativity had been swamped by inane commercialism, he painted – you guessed it – a crucified Santa.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks