Brooke Shields's new QVC fashion collection really is 'Timeless'

Nothing comes between Brooke Shields and her new brand. The aptly named Timeless collection eschews trends and transcends the decades... but it is the model’s history that makes it so appealing

Brooke Shields draws herself up to her full 6 feet, fielding reporters’ questions with an agility that has become second nature.

At the Beekman Hotel in downtown Manhattan at the end of January, Shields, model, actress and veteran of numberless interviews, is delivering but the latest in a series of canny performances. She banters good-naturedly, as is her habit, displaying an unflappable poise and a set of curves pneumatically packaged inside a close-fitting top and skirt from the collection she is about to unveil for QVC.

Her features and frame are considerably fuller than in 1980, when she scandalised television audiences with the coy claim that nothing comes between her and her Calvins. The once angular jaw is softer. Not that it matters. At 52, Shields, after transitioning through the decades from wide-eyed innocent to self-mocking glamorista in television shows like Suddenly Susan and Friends, has ripened into the kind of consummately relatable personality much coveted by QVC, the home shopping behemoth that found success with celebrities such as Iman and Catherine Zeta-Jones.

Shields’s history is part of the draw. On-screen and on the page, she has been a continual presence in the lives of her fans: a comedic talent and the author of several viscerally revealing memoirs in which she casts herself as a survivor, beating back demons that include a codependent relationship with an alcoholic mother and a severe episode of postnatal depression.

As Rachel Ungaro, vice president for fashion merchandising and design development for QVC, once said: “She transcends the decades” – fixed firmly in home viewers’ imaginations as paradoxically tough and alluring but approachable.

“Our customer is going to love her,” Ungaro says, “because to their minds she is very real.”

Still, the notion of Shields tweaking hemlines and adjusting seams seems a bit improbable.

True, during his first season as creative director for Calvin Klein, Raf Simons resurrected her famous jeans-clad image on a series of T-shirts. And last year a taut, preternaturally youthful Shields modelled Calvin Klein lingerie in Social Life magazine. But full lips and furred brows aside, her influence on fashion is debatable.

Unlike many models who are over 50 or performers parlaying their celebrity into late life fashion careers – Jaclyn Smith and Marlo Thomas come to mind – Shields, surprisingly, has never put her name to a fashion line.

Still the QVC partnership seems promising. Her new label, Brooke Shields Timeless, is trend-free. It is aimed unabashedly at the “menocore” crowd, a cohort archly defined by Harling Ross on Manrepeller as “like normcore, if its inspiration were women of a certain age”.

But Shields will tell you she is not all that readily typecast.

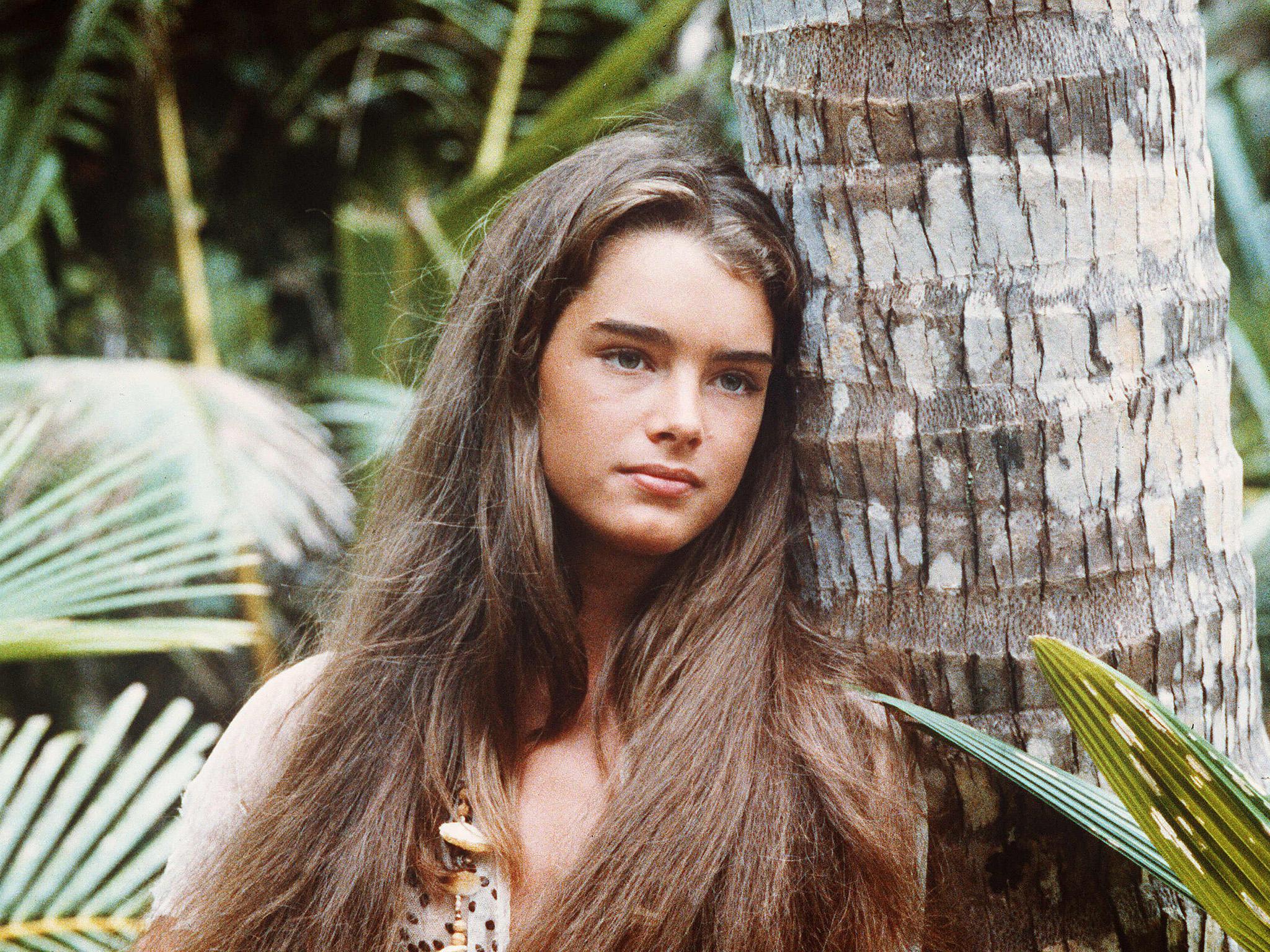

Members of the 35 to 65-year-old QVC demographic may recall her as the paradoxically chaste pin-up who courted notoriety playing a preadolescent prostitute in Louis Malle’s 1978 film Pretty Baby. They may also remember her as the demiclad nymph cavorting on a desert island in The Blue Lagoon (1980), her breasts curtained by nothing but her waist-length hair. A disconcertingly sultry naïf, she made her mark on a culture skittishly poised between prurience and an uneasy puritanism.

At the end of the day, you’re sort of asking yourself, ‘Who am I?’ Am I honestly OK with being more than just one thing?

“I think in my life I’ve really embodied both the sexy and the wholesome,” says Shields, a tutor’s pet on her early movie locations who eventually attended Princeton University. “In school I was a goody-goody. I would do all my homework. But if I’m in a rock’n’roll setting, I want to be able to channel whatever it is that’s behind it.”

Still, as she’ll also tell you matter-of-factly, she remains a work in progress. Days after introducing the QVC line at the Beekman, she gusts into Maison Kayser, a West Village bakery near the townhouse she shares with her husband, Chris Henchy, a television writer and producer, and their two daughters, aged 11 and 14. Seasoning her eggs with a vial of Tabasco she produces from her purse, she is easygoing but reflective. “At the end of the day, you’re sort of asking yourself, ‘Who am I?’” she says. “Am I honestly OK with being more than just one thing?”

And yet her variability is arguably what has extended her appeal. Recurrent gossip column fodder, the youthful Shields dated John Travolta and crushed on a baby-faced George Michael. Later in life she found herself deflecting the advances of Donald Trump, who had suggested that they date, telling her, as she amusedly told talk show host Andy Cohen, “You’re America’s sweetheart, and I’m America’s richest man.”

She was briefly married to tennis pro Andre Agassi, who portrayed her in Open, his 2009 autobiography, as a socially ambitious gadabout to his off-the-court homebody. They were a mismatch, not least because, as he writes, when friends appear, “It feels as if we’re actors and our guests are an audience.

“She playacts,” he adds, “even when the audience isn’t here.”

In her 2014 memoir, There Was a Little Girl: The Real Story of My Mother and Me, Shields confides that she pulled away from Agassi by degrees, their rift widening after she learned of his former substance abuse. “I feared our life together was not based in absolute truth,” she writes.

Throughout her marriage and well into Shields’s adulthood, Teri Shields, her notorious hovercraft of a mother, was both her bulwark and her bane. Energetic and capable, but often drunk, the senior Shields is portrayed in her daughter’s memoir with an unlikely blend of solicitude and pain. (Teri died in 2012.)

Teri Terrific, as she was known among friends, was much maligned in the film industry as a harpy who exploited Brooke Shields and turned her into an unprotesting meal ticket. She encouraged Brooke, who was scarcely out of puberty, to act as camera bait, strutting provocatively at movie premieres and Hollywood galas.

At the same time, Teri Shields made certain no drugs or whiff of scandal would ever taint her charge. But if she guarded Brooke’s virtue with a gorgonlike ferocity, it was partly in the interest of a payoff.

You may expect the mature Brooke Shields to claim the status of poster woman for the #MeToo movement, calling out a long line of predatory studio honchos who beat a path to her trailer. She does not.

“There were no Harveys or James Tobacks in my life,” she says evenly. “My mother absolutely was the barrier between me and all of them. They couldn’t get to me. They were not going to get through because it was too much work.”

Her real harassers were a prurient media and psychically assaultive public. “There seemed to be no boundaries,” she writes in one of her memoirs.

At first I shied away from that. I didn’t want to be a commodity. I wanted to be real. But the flip side was that I wanted to sell. And you can’t have it both ways

To the hordes of autograph seekers nipping at her heels, “I could never say no,” she recalls. “I felt as if the world owned me.”

Over the course of her somewhat patchy upbringing, Shields acquired a robust armour. Teri Shields spent part of her girlhood in Newark, cleaning other peoples’ houses. Divorced when Brooke was a toddler from Frank Shields, a well-born and glamorous business executive, she and Brooke spent summers in Southampton, New York, in a relatively shabby part of town, so that Brooke could see her father.

“I was the person who was living above the hardware store and was fine with it,” Brooke says. “At the same time, I was going to day camp with all these extremely wealthy kids and, you know, I could fit in there.”

That duality is reflected in the QVC collection. Priced from $29 to $109 (£21-£77), it veers in tone and style from classically upscale to breezily accessible. The company planned to introduce the line at the Beekman in a setting the designer dismissed as not quite up to snuff. In a misguided play on the “Timeless” label, QVC had installed clocks on every available wall.

Shields wasn’t having it. “I wanted the space to feel inviting, not kitschy,” she says.

She and her manufacturing partner, KBL Group International, had approached QVC, a move that she says took courage. The prospect of fusing her country club-inflected aesthetic with something a bit more democratic was daunting at first.

Even simply getting dressed has sometimes proved a challenge. “I was afraid that I didn’t have a through line to my style,” she says. She struggles to make sense of her more than 50 pairs of jeans and rarely worn high-end togs from labels including Carolina Herrera, Rodarte and Saint Laurent.

“I had nice things, but I was afraid I was going to sweat in them and spoil them,” she says. Instead of picking up fancy labels, she says, “I would buy 10 identical pieces from Uniqlo.” More pointedly, she says, “I didn’t want to seem better than anyone else.”

Her egalitarian tendencies gave rise to a collection of discreetly striped shirts, tank tops with jewelled necklines, trench jackets, tunics and wide-leg trousers, a wardrobe that highlights and simultaneously downplays the signifiers of wealth and class.

When she is not overseeing the placement of zippers, buttons and seams, Shields is shuttling between New York and Los Angeles, where she is taping Jane the Virgin, parodying herself as an actress and supermodel called River Fields.

Off set, though, she plans to stay sharply focused on Brooke, the brand. “At first I shied away from that,” she says. “I didn’t want to be a commodity. I wanted to be real. But the flip side was that I wanted to sell. And you can’t have it both ways.”

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks