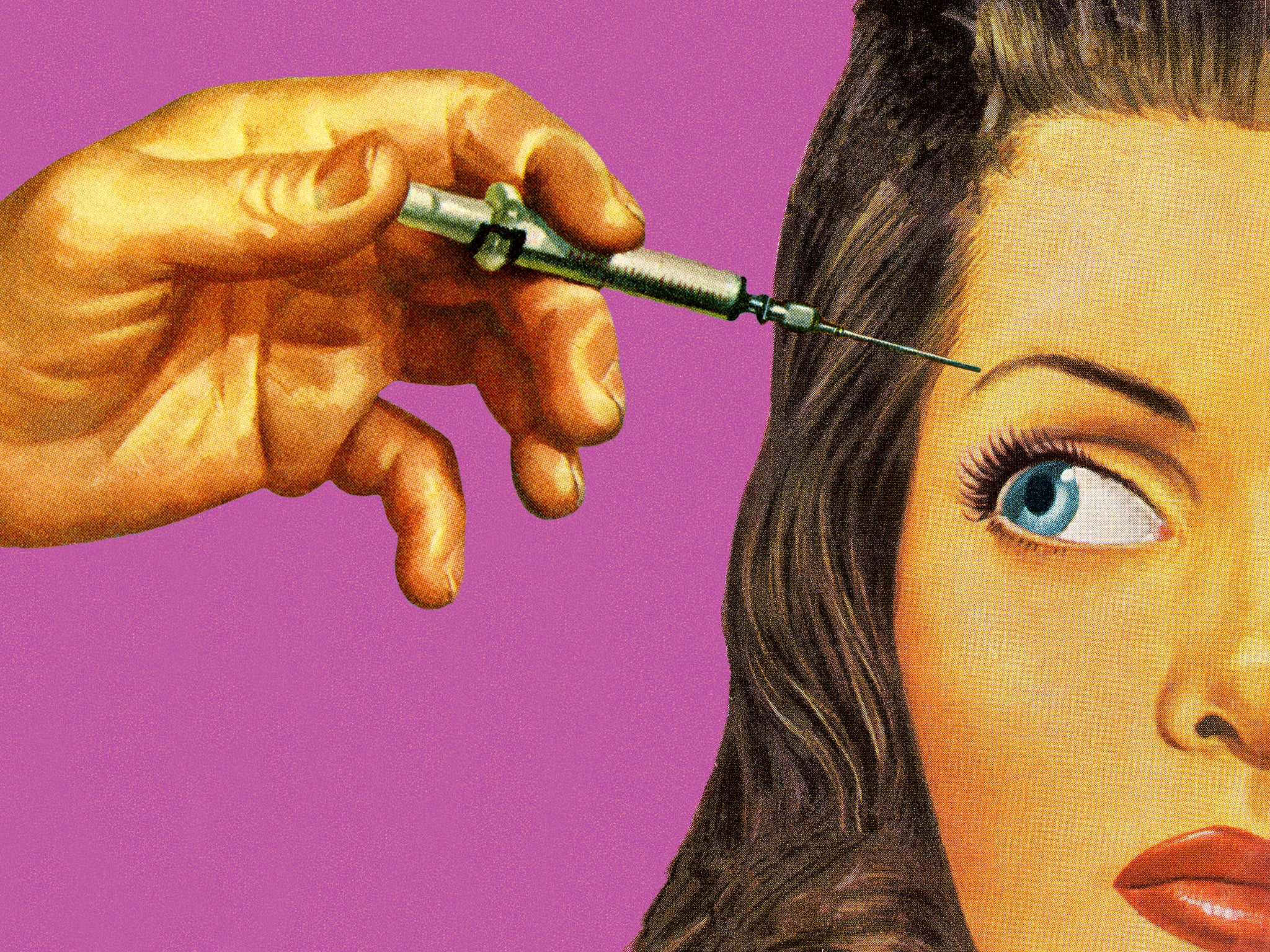

Young, wild and toxed: Why are so many twentysomethings getting Botox and filler?

British dermatologists have spotted an alarming increase in the number of young people using dermal fillers and Botox, while former Disney hunk Joe Jonas is busy promoting Botox’s biggest rival in a move to directly push injectables on young men. How did all of this become so commonplace, asks Ellie Muir

Last year, Connor paid £800 for 6ml of dermal filler to be injected into his chin, jawline and cheekbones. He is 23. “I was paying for it in monthly instalments because I couldn’t afford it all at once,” he recalls. Connor’s choice to get dermal filler was a solution to his long-held insecurity about the shape of his face. “Since I was around 15 or 16, I’ve always wanted to have a more defined face. I would use apps like Facetune when I was younger to edit my face to see what it would look like.”

After he was injected, Connor’s self-esteem was boosted in an instant. “My jawline was sharper, my chin was more square and my cheekbones were more enhanced. I was feeling so insecure in that period before the treatment. I just wanted something to improve my confidence.”

Connor isn’t alone. Under the mounting pressure of toxic beauty standards, young people are frequently turning to non-surgical cosmetic treatments. Use of dermal fillers and Botox, in particular, have grown in popularity among people in their twenties. Right now, there is no age-specific data to reveal the true magnitude of the trend as it unfolds, but medical professionals are anecdotally spotting the situation. “The popularity among young people for non-surgical cosmetic procedures has been recognised as rising,” says Dr Tamara Griffiths of the British Association of Dermatologists.

Though it’s easy to point fingers at the Kardashians or ITV’s Love Island for pushing unattainable beauty ideals onto our screens, young people are racing to achieve the plumpest pout or the highest cheekbone as a result of the latest aesthetic trends.

A decade ago, Botox and injectables were seen as reserved for older, wealthier people who could afford Harley Street treatments, including celebrities fearing the appearance of ageing. Now, aesthetical treatments among people in their twenties are abundant; some seek preventative Botox, an injectable toxin that temporarily relaxes the facial muscles that cause wrinkles and fine lines. But the most popular among twentysomethings is dermal filler – an injectable substance with hyaluronic acid that’s used to fill lines and wrinkles, or to add volume to and accentuate parts of the face.

Connor is just one of thousands of people around his age who’ve sought said treatments. “I’ve noticed my friends casually saying that they want to get filler done, whether in their cheeks or lips,” he says. “It’s a conversation I hear a lot.”

Helen, 22, is studying criminology and sociology at university and recently got 1ml of dermal filler injected into her lips. “I went to see this lady in a hair salon in Portchester, who I found through Instagram,” she says. Helen achieved her goal of having fuller lips and feels pleased with the outcome. “It’s completely changed my perception of how I looked before. When I look back at pictures, my lips look small – it’s kind of warped my perception of my face.”

More broadly speaking, though, young people are in a self-esteem crisis. It’s been raging ever since we opened our first Facebook accounts and began using photo editors like Facetune. Medical professionals are even starting to panic about it.

“I’d be very cautious about treating anyone under the age of 25 for cosmetic reasons,” says Dr Griffiths. “Younger people can sometimes be vulnerable in terms of unrealistic expectations, pressures from social media and [their] peer groups in addition to [experiencing] anxiety, depression and other mental health issues.”

Victoria Brownlie, Chief Policy Officer at the British Beauty Council, agrees that the amount of people seeking aesthetical treatments has grown exponentially, and could have dangerous consequences. “We know anecdotally of ‘the Love Island effect’, [with] the younger demographic being heavily influenced by those they are seeing on their screens and social media feeds,” she says. For 2020, the Department of Health estimated that as many as 41,000 Botox procedures were carried out on those under 18 (the UK has since banned the procedures for minors under The Botulinum Toxin and Cosmetic Fillers Children Act). But for those above the age of 18, there is little to stop them from plumping and priming their faces. Nor support to tackle any deeper issues at work.

Due to their ages, Connor and Helen were both guinea pigs of Facebook and Instagram, growing up seeing unrealistic body images and examples of idealised beauty online – it’s almost inevitable that they and many like them therefore fantasise about changing their appearances.

Research conducted by body care brand WooWoo found that one in 10 British women said they “hate everything about their body”, while over a third said pressure about their bodies came from social media. But Connor is adamant that toxic beauty standards are placed on all genders. “People don’t realise that men can feel the pressure to look a certain way, too,” he says. “If you’re a gay guy on social media, like me, there is a slightly greater pressure to look a certain way.” Beauty culture is therefore demanding more of all genders, as the baseline of beauty becomes increasingly unattainable and more expensive to achieve.

There are even celebrity-backed product campaigns currently targeting male consumers. Ex-Disney star Joe Jonas recently appeared in an eerie new advert for Xeomin, Botox’s biggest competitor, titled “Beauty On Your Terms”. Xeomin is a cosmetic injectable product that smoothes fine lines and wrinkles. In the video, a fresh-faced, poreless Jonas lies in bed, telling the camera about his own experience using injectables, delivering the line: “There’s no one way to define beauty. With a smart toxin like Xeomin, it’s on my terms.”

As celebrities become more candid about their treatments, young people become inspired to try the procedures themselves. Like a chain reaction, beauty technicians are taking advantage of the current demand for injectable cosmetic treatments; many unlicensed technicians are seeking inadequate short courses and one-off training sessions from “certification bodies”, offering affordable treatments to people with smaller budgets. It means that venues like high street hair and nail salons and tanning studios can offer a plethora of cheaper, accessible treatments like lip fillers, vampire facials and vitamin injections.

Currently, dermatologists and ministers are aiming to crack down on the unregulated administering of treatments. “At present, there is little regulation around non-surgical cosmetic procedures,” Brownlie says. “Some local authorities require businesses to hold a ‘Special Treatments Licence’ to offer certain aesthetic procedures, but this is not UK-wide.”

Last February, the government announced its intention to introduce a licensing regime for non-surgical cosmetic procedures such as Botox and fillers. “We understand that the current cost of living crisis might tempt some to shop around for cheap treatments,” says Andrew Rankin, a trustee at the Joint Council for Cosmetic Practitioners. “There is a cost associated with the professional use of genuine products and we would recommend people avoid treatments that appear too cheap.” If the government passes the intended legislation, the department for Health and Social Care would be granted regulatory powers to ensure consistency across the aesthetics industry, and protect clients from unlicensed practitioners.

As for Connor, he was disappointed when his first round of filler – which he was told would last up to 18 months – was only visible for three months, making his self-esteem kick short-lived. “I won’t get the treatment again until I can afford to do it comfortably,” he admits. “If you’re around 20 years old [and] want to get filler done, my advice is to wait, because you never know how your face is going to change. Think about how long it will last and if you can afford for it to last that long.”

Dr Griffiths agrees: “If you’re in your twenties and are seeking these treatments, think twice. Don’t do it as a knee-jerk reaction or spontaneously, have some time out to consider why.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks