How could I explain death to my son after the loss of his baby sister?

Emma Poore struggled to help her son understand the death of his baby sister, so she wrote a picture book to help him and other families suffering bereavement

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

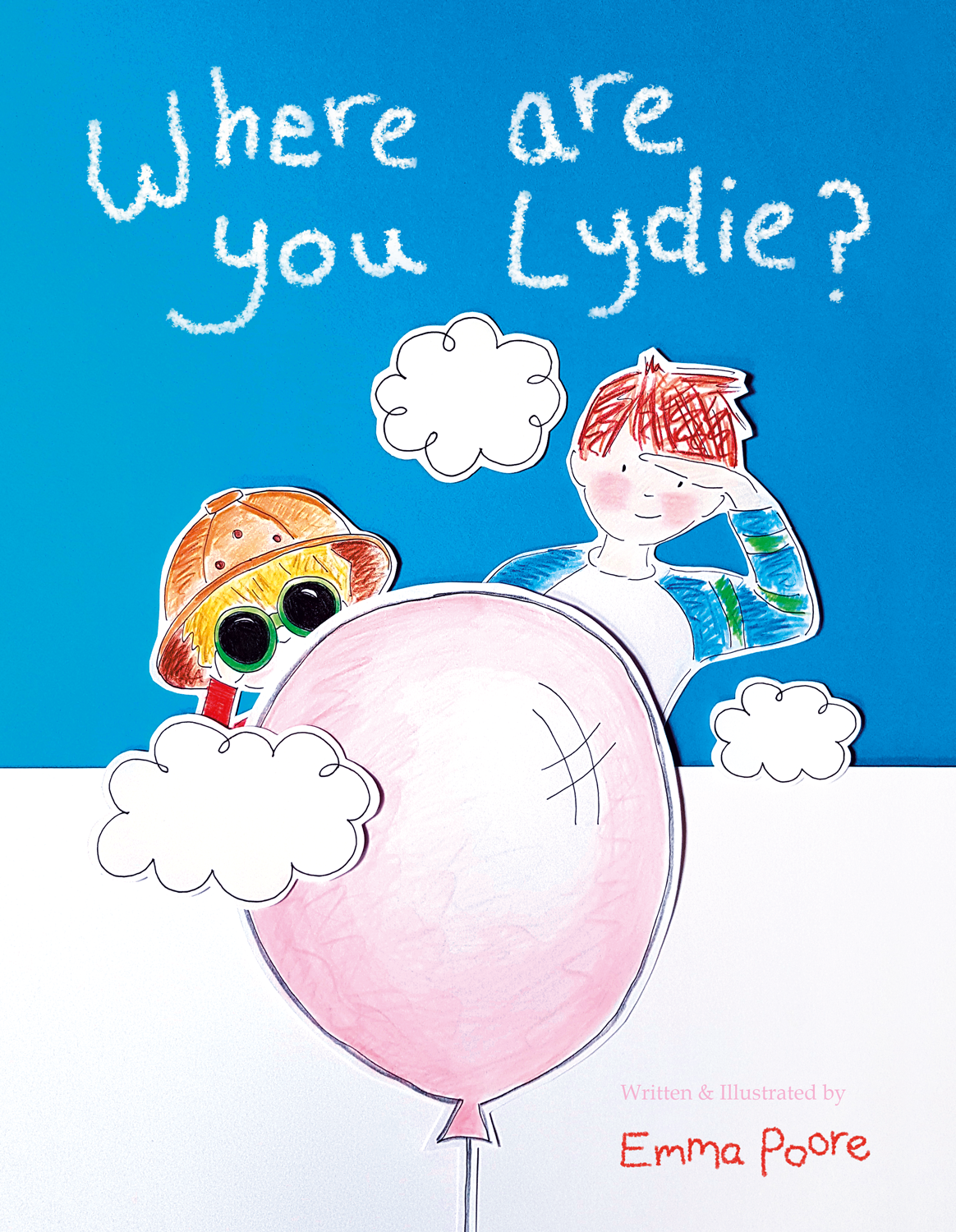

Your support makes all the difference.July is National Bereaved Parents Awareness Month. One in four pregnancies will end in miscarriage and nine babies are stillborn every day in the UK, yet there is still enormous taboo around speaking openly about pregnancy and baby loss. In 2010, when Emma Poore was 24 weeks pregnant, her baby daughter Lydie died. Emma’s elder son George was three years old at the time. Emma has since written an illustrated book called Where are you Lydie? to help young children, siblings and families going through loss.

Nine years ago on Easter Sunday, I should have been at home, waddling pregnant around the garden, hiding chocolate eggs for our three-year-old son George to find from the Easter Bunny. Instead, I was giving birth to my lifeless daughter.

Our baby died when I was 24 weeks pregnant. Tim and I waited over 24 hours on the delivery ward for a room to become available for us. We lay awake throughout the night listening to other couples become parents, hearing other babies cry for the first time. There was no specialist bereavement midwife to advise us, no bereavement suite and we didn’t qualify for any support or counselling. We left the hospital without our daughter, and only a handful of leaflets.

When your child dies, your world changes forever. Your life, your dreams, the way you think and the way you live are never the same again. Nor for your family. Grief becomes your shadow.

We had the unthinkable task of trying to manage the grief of our son, George, who had been so excited about having a baby brother or sister. As parents, we couldn’t find the right words to explain or find anything suitable to read with him that might help him make sense of what had happened. There were a few books that vaguely touched on death, but certainly not the death of a baby or sibling.

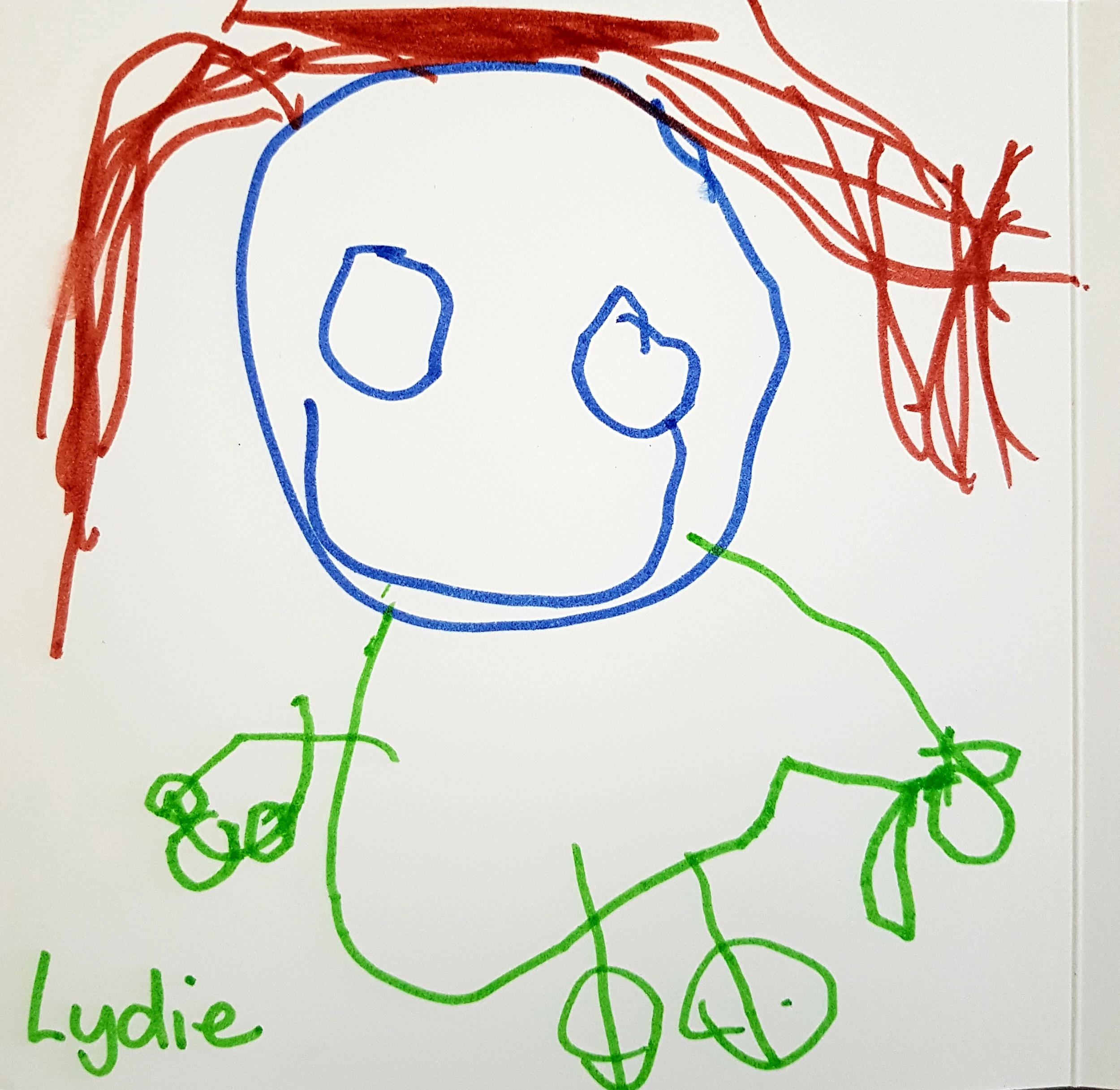

George asked a lot of questions, often very directly, which were really difficult and painful to answer. He wanted to take toys to Lydie, asked if he could go in a rocket to see her, drew her pictures, asked if she was alone or cold. It was heartbreaking.

I tried so hard to keep it together for him. I’d wait until he was at nursery or asleep before putting on the music from Lydie’s funeral and sobbing silently. It was exhausting. Grief is isolating and selfish. The sight of another baby girl or another baby crying felt like a knife. I couldn’t bear it.

In the first few days after Lydie’s death, I often said the wrong thing to George without knowing, because I wanted to protect him, to somehow soften her death for him. I said she had “gone to sleep”, but then he wouldn’t go to sleep. Or that she had died because she was “ill”, but then if George was ill he’d worry about dying.

Sands, the Stillbirth and Neonatal Death Charity Bereavement Support Line, became my lifeline. It helped to talk to someone who understood. I learned I wasn’t helping George to grieve properly, as I was giving him the wrong messages.

Young children don’t understand the finality of death or what the term “dead” means because cognitively children under five haven’t yet developed an awareness of death. They don’t understand that life functions stop when someone dies. George was confused as to how Lydie could be dead but also be in “another place” at the same time. He would be very upset one minute or ask a very direct question, and then promptly go out to play and seem fine the next.

In my book Where are you Lydie?, George says to Henry [their youngest son, born just under two years after Lydie’s death] “Mummy says she’s a special kind of fairy in a beautiful magic land, why can’t I go there and see her? Where is it?” and later goes on to say in confusion, “But you can’t be in three places at once Henry, Mummy says that too.”

I remember one time when George was around six years old he asked if we could send Lydie a piece of cake on her birthday and if a balloon would take it to her. It was the first image I drew for the book seven years later.

Henry, our youngest child, is also very much a part of the book. Even though he was born after Lydie, he wanted to know about her and talks about her a lot. He also wants his friends at school to know he has a sister. He took the book into school recently to show his favourite teacher. It was a huge thing for a seven-year-old to do and incredibly emotional for me.

It is life-changing for a child to lose a sibling at any age. That’s why it is so essential to create a safe space to talk with bereaved children and to let them grieve if they need to. As a family, we are definitely moving forward with a much better chance of recovery by being honest and open.

I am so proud of all three of my children. I really hope that together we can help other families who tragically may have lost a child.

Where are you Lydie? is a book that is sensitively-written and illustrated for siblings between the ages of three and seven years old. It is a facilitative story and guide for parents, grandparents, teachers and caring support professionals to start those difficult conversations or explore the questions that may come up in a safe and inspiring space.

To find out more about Emma’s journey and to buy this book, in association with Sands, please visit www.emmapoore.co.uk or contact Emma directly on emma@emmapoore.co.uk.

If you have been affected by any of the issues raised in this article, you can contact stillbirth and neonatal death charity Sands on 0808 164 3332 or email helpline@sands.org.uk. The helpline is open from 9.30am to 5.30pm Monday to Friday, and until 9.30pm on Tuesday and Thursday evenings.

You can contact the Miscarriage Association helpline on 01924 200799 or email the charity at info@miscarriageassociation.org.uk. The helpline is open from 9am to 4pm Monday to Friday.

You can also find bereavement support at The Lullaby Trust by calling 0808 802 6868 or emailing support@lullabytrust.org.uk.

To contact Petals to enquire about the charity’s counselling services, you can call 0300 688 0068 or email counselling@petalscharity.org.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments