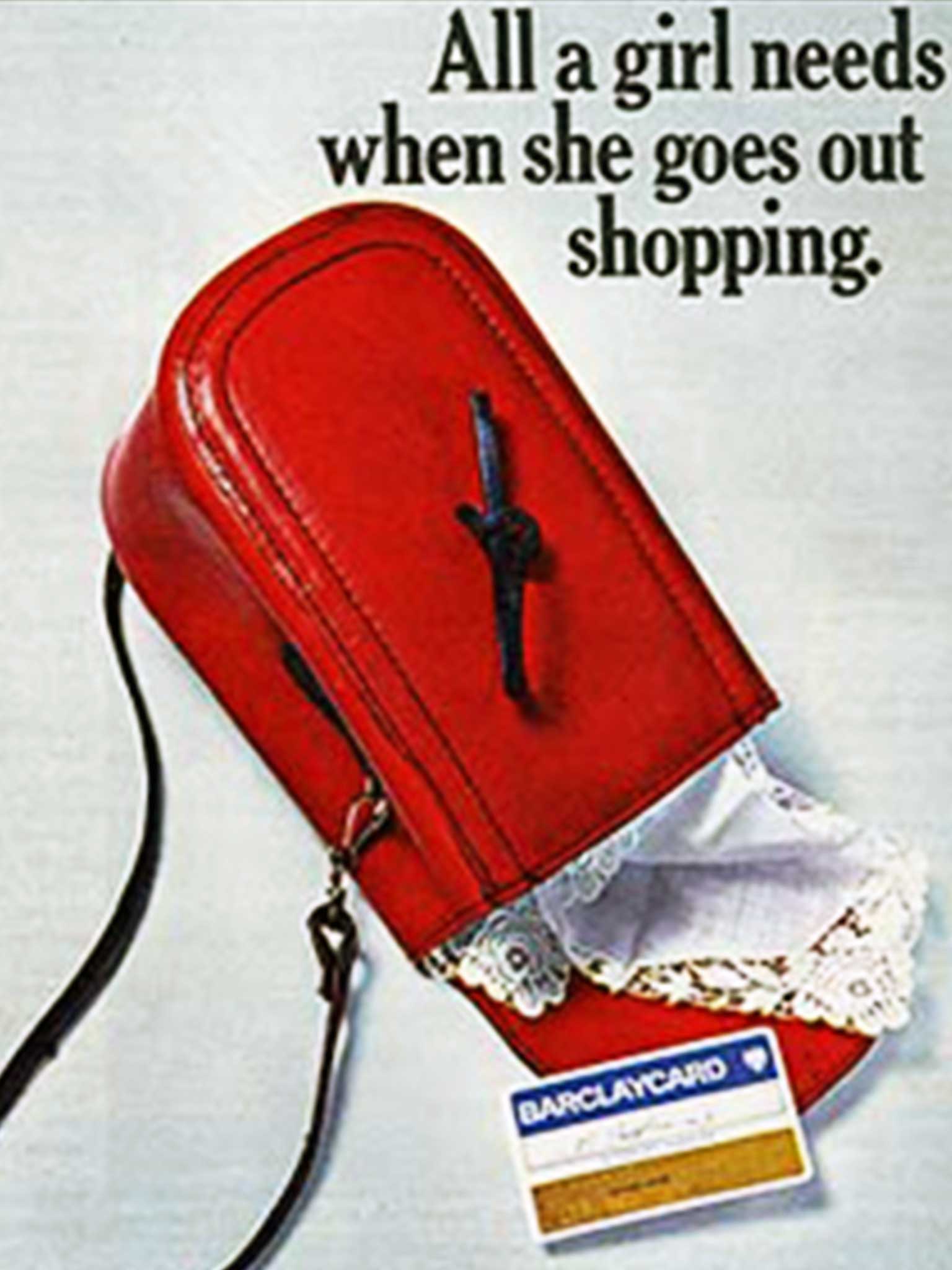

Barclaycard turns 50 this month, but is there much to celebrate?

Barclays launched its first credit card in 1966. Sean O’Grady takes a look at the history of spending, the accumulation of debt and how we are all living beyond our means

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.So: the Barclaycard, the first proper credit card in Britain, celebrates its half-century. Cause for rejoicing? Or deep abiding national regret?

It was, and is, a boon. Before Barclaycard there were various charge cards, such as American Express, but these tended to be instruments of convenience rather than extended credit – they had to be paid back, in full, in short order.

In a way the idea of credit is nothing new: there have always been financial IOUs. The recent discovery in the City of London of a wooden Roman promise to pay – they didn't have magnetic strips or touch technology in those days – is a reminder of that. It is dated 8 January, 57AD and ackowledges that someone owed a trader 105 denarii for some merchandise. After all, the word “credit” derives from the Latin for trust. But the modern credit card was special and novel, because it separated your assets, mainly your current account from your liabilities and you could take time to pay it back.

In those days it was highly elite. In the 1960s most of the population didn't even have a current account with a cheque book; wages were paid in cash and readies paid for everything, from a paper and the football pools, to the rent.

After Barclaycard and the others became established, as financial deregulation and prosperity spread in the decades following, we entered a marvellous new world where virtually anything – a pair of shoes, a meal in a restaurant, even a car – could be purchased with a wave of the “plastic”. It used to be a slightly special affair. Shops and restaurants would have little plastic signs in the window or on the door declaring “Barclaycard accepted here” or “Welcome Access”. Access, by the way was the rival to Barclaycard set up a few years later by Barclays' more slow-footed rivals – NatWest, Lloyds, RBS and the now forgotten Midland Bank. In due course it became Mastercard, and by the 1980s just about every major financial institution in the world had entered this lucrative market.

After all, with a typical annual interest rate (correctly calculated) of about 30 per cent and customers almost wilfully neglectful of the fact that this was, and is, an expensive way to borrow money – and a lucrative way to lend it. There were fat profits to be made. By the end of the 1990s the competition for customers had become so fierce that multiple unsolicited offers through the post of zero per cent rates for a year, turned many of us into debt junkie “rate tarts” – making a small monthly minimum repayment on a 10 grand debt and transferring it to a new card provider every six months, just before the interest charges kicked in. I too was a rate tart, merrily recycling my debt from NatWest to Barclays to Nationwide to Alliance and Leicester to MBNA to Capital One to Barclaycard and back again. This may have inflicted some – unfair – damage on my credit rating.

By the 2000s nearly everyone had at least one credit card, as well as their debit card, while shop-specific store cards also reached peaks of popularity, despite even higher interest and late payment charges. Cash had started its decline; it was used in less than half our transactions for the first time in 2015.

One wouldn't want to overstate it, but this plethora of cards, their ease of use and often generous instant spending limits – £5,000 or more even for people on modest wages – played their part in creating the credit boom that inevitably ended with the credit crunch, banking crisis and the Great Recession in 2008. An awful lot of global credit card debts, unbeknown to the people who bought their new telly or paid for their honeymoon via plastic, were aggregated by investment banks into blocks of bonds, and then diced and sliced over and again into a pyramid of “collateralised debt securities”. These were then sold on and sold on, to banks, investment houses, insurers and pension funds, and used as collateral for yet more debt creation. In the end some of it turned out quite worthless – “toxic debt”. It cost us all a great deal to clean the mess up. As we all know.

If the first Barclaycard was introduced in 1966, then I joined the party about a third of the way through, as a student in the early 1980s, and not one with any assets to call upon beyond my natural wit. As soon as I got my hands on my Lloyds Bank Access card, I bought a pair of Doc Martens shoes, a style I still favour, and I remember the dizzying effect it had on me. I didn't need any money! The shop assistant wrote down, by hand, the details on a slip of paper with some sort of greaseproof sheet on the back – the counterfoil. I signed it. Then she placed the card underneath the slip into a contraption with an ink roller on top. The roller made an impression of the card, and that was that. Such a mechanical ceremonial seems as far away today as that ancient Roman wooden cheque. In any case, in the spring of 1982 I too had been inducted into the something for nothing society.

Today, we have £64.4 billion of credit card debt in the UK. We owe almost as much as we did before the crash, and the debt is edging up again. One of Britain's great dirty secrets is that much of the improvement in living standards we have enjoyed over the years has been funded by borrowing: consumers borrowing from banks; the nation borrowing from foreigners. As individuals we have become too used to spending more than we earn, and the British as a whole are too reliant on the willingness of overseas investors to fund our trade deficit. In the case of the poor, they are often forced to borrow merely to survive, from “payday lenders”, who use sophisticated algorithms, clever marketing and the internet to conduct their trade, charging 1,500 per cent a year.

The longevity of Barclaycard and its many peers – there are hundreds of bits of plastic to choose from – show how very ingrained the British debt habit is. After all the talk – some of it going back long before 1966 – about rebalancing the economy, the British are still more interested in borrowing, spending and consuming than in investing, making things and exporting. If only we could be so innovative in the rest of our economy as we are in the field of personal finance, we might not be perpetually living beyond our means.

I don't have a credit card anymore, by the way.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments