The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

How baby boomers became the most selfish generation

Over the past 40 years, the US government has done precious little to invest in the future.

Instead of spending money on education, our government has repeatedly chosen to cut taxes. Instead of investing in infrastructure, politicians have several times shut down the government over budget disputes.

Time and time again difficult decisions have been pushed off for later, and complicated social issues have been relegated to something that the unforgiving "invisible hand of the market" can fix.

It has all been to our detriment. And it is all our parents' fault.

The baby boomers who have controlled this country since the 1980s are a selfish, entitled generation. It is not your imagination, and it didn't come out of nowhere.

This is a short review of the ideas that made them that way.

But first, a note from economist John Maynard Keynes:

“The ideas of economists and political philosophers, both when they are right and when they are wrong are more powerful than is commonly understood. Indeed, the world is ruled by little else. Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually slaves of some defunct economist."

Our man, Milton

And so it is in this case.

"The defunct economist in this case is Milton Friedman, who persuaded a generation that selfishness was the natural state of humanity and that selfishness ultimately would lead to the best possible society, when all the empirical data shows exactly the opposite: that people are capable of prosociality and that pro-social societies do better," Lynn Stout, a professor of economics at Cornell, told me in an interview.

Toward the end of the 1960s and in the early 1970s, Friedman was the champion of a school of thought in economics called neoclassical theory.

According to this theory, every human action is motivated by selfishness. As such, all humans can be motivated into doing anything as long as there is an economic incentive for it. In fact, no one does or should look out for the good of the collective — corporations should worry only for their shareholders and not for their workers or their customers, for example. Individuals should think only about their own bottom line. It's all that matters to them really, anyway — the me, here, and now.

It took some work for this ideology to become mainstream, though, because Americans didn't always think this way.

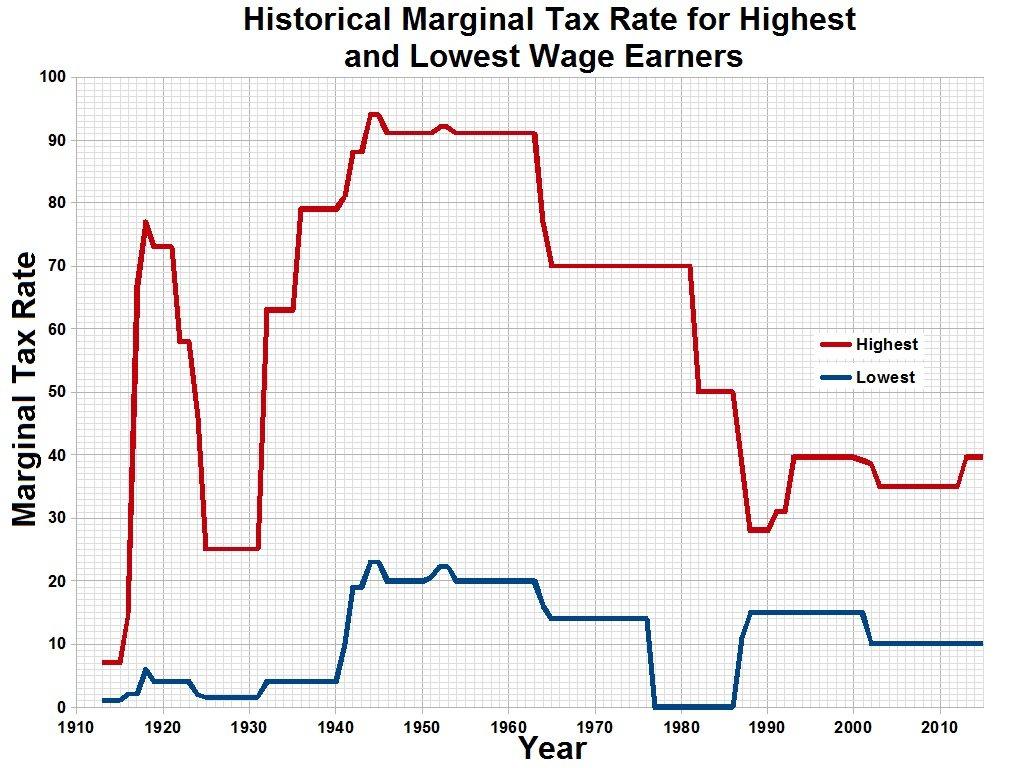

From the 1920s to the 1960s, corporations were expected to take care of their workers and their communities. And citizens were encouraged to do the best for their country. Taxes were high, workers were well paid, the middle class was built, and America prospered.

But there were stumbles, and Friedman and his ilk took advantage of a major one in the 1970s: When the US abandoned the gold standard and the price of oil exploded, neoclassical economists blamed regulation for the country's economic malaise.

Protections for workers were undone. Unions were busted. And serious politicians started to argue that cutting taxes for the rich would benefit everyone, as those cuts would encourage the wealthy to spend more money that would "trickle down" to the rest of the populace.

Former New York Times executive editor Bill Keller put the results of this ideology in a perfect paragraph back in 2012:

"In 1962, we were laying down the foundations of prosperity. About 32 cents of every federal dollar, excluding interest payments, was spent on investments, only 14 percent on entitlements. In the mid-70s the lines crossed. Today we spend less than 15 cents on investment and 46 cents on entitlements. And it gets worse. By 2030, when the last of us boomers have surged onto the Social Security rolls, entitlements will consume 61 cents of every federal dollar, starving our already neglected investment and leaving us, in the words of the study, with 'a less-skilled work force, lower rates of job creation, and an infrastructure unfit for a 21st-century economy.'"

Neoclassical economic theory is behind all of this. It was behind the draconian budget cuts of the Reagan administration that also came with tax cuts for the wealthy. It was behind the Bush tax cuts, too. It was also behind Clinton-era banking deregulation, namely the end of the Glass-Steagall Act, which sowed the seeds of the financial crisis. It is behind the growing wealth gap that has dragged our country down — politically and economically — for decades.

"The neoclassical theory of everyone acting selfishly does not get you to peace and prosperity," Stout told me over the phone. "The way societies prosper is by cultivating conscience."

'Ask not what your country can do for you ...'

That, of course, prompts the question: What is the American conscience?

Neoclassical economics was developed, in large part, as a counter to communism. We are not communists. We are capitalists; the question is how we want to bring that to bear on society. Do we do it with violence, allowing the market to rip at the fabric that holds communities together — families, schools, shelter, health?

Or do we do it generously, so that future generations can trust that their country will remain intact?

There is a very American way to engage in capitalism that also ensures that corporations take care of their workers and that the government takes care of its citizens. It's called "future preference," and Bill Clinton referred to it in his acceptance speech for the Democratic Party's presidential nomination in July 1992:

"America was the greatest nation in history because our people had always believed in two things — that tomorrow can be better than today and that every one of us has a personal moral responsibility to make it so ...

"Of all the things that George Bush has ever said that I disagree with, perhaps the thing that bothers me most is how he derides and degrades the American tradition of seeing and seeking a better future. He mocks it as the 'vision thing.'"

It was the lack of a "vision thing" that made George H.W. Bush promise that he would not raise taxes when he ran for president in 1988. Of course, he eventually did. Our economy demanded it, and Bush was ultimately a pragmatist, not an ideologue.

Unfortunately, now the ideologues are fully in charge of Washington. Donald Trump, a baby boomer who has bragged about not paying taxes, is at the head of the government. He has surrounded himself with economic advisers who will again cut taxes for the rich. He wants to appoint an education secretary who does not believe in making all public schools vibrant and competitive but believes in allowing the market to dictate which schools should and should not survive (an abdication of our responsibility for the future in its purest form).

What you will get from this, of course, are policies firmly rooted in selfishness.

And now, my friends, we are in danger

Stout called today's neoclassical economists "a generation of intellectual slaves."

I call them the people who brainwashed House Speaker Paul Ryan.

Over the next few months, Ryan will attempt to dismantle Obamacare and privatise Medicare. His plan to replace it involves just giving seniors a $20,000 voucher to pay for healthcare. Of course, for many of our society's most vulnerable, that won't be enough. And who knows whether they will have insurance coverage to help them. The private sector does not prioritise the needs of our country's most helpless.

So why do people think we should leave them to the unyielding hand of the market?

Neoclassical economists believe that the private sector does things better because the incentives are more selfish. S0 why not let the private sector handle everything — even the most vital of human needs?

Here's why: The incentive theory doesn't really work when the people being served are not also the people paying for the service. This is the case in education (taxpayers pay, but students learn). This is the case with healthcare (insurers pay the bulk, but patients decide when to see a doctor).

In a selfish system, ultimately the payer's needs supersede everything else. We've seen this play out brutally in the case of incarceration. For-profit prisons have been such horror that the Justice Department decided to phase them out.

For-profit colleges have also been a disaster; last year the Department of Defense said it would no longer allow service members to use its funds to attend the University of Phoenix, the country's largest for-profit college owned by the Apollo Education Group.

A Trump administration is expected to reverse several decisions such as these.

"All of our social cues are telling us to be selfish right now," Stout said. Baby boomers love this, because it means they do not have to consider the needs of others or sacrifice for anyone outside their immediate networks.

"And of course, very rich plutocrats support this because it allows them to continue being very rich plutocrats," she continued.

There is hope, though.

Millennials, a generation even larger than their parents, have grown up watching this selfishness in action. They watched how the recklessness of the housing boom and bust wreaked havoc on our society and forced them to reach adulthood in a world in which opportunity is shrinking. They do not benefit from the selfishness of their parents.

And hopefully they will not emulate it either.

This is a column. The opinions and conclusions expressed above are those of the author.

Read more:

• This chart is easy to interpret: It says we're screwed

• How Uber became the world's most valuable startup

• These 4 things could trigger the next crisis in Europe

Read the original article on Business Insider UK. © 2016. Follow Business Insider UK on Twitter.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments