Artisan cafés and luxury flats: How bad can gentrification really be?

How can poor people hang on when the developers move into an area – and how can the incomers atone? In New York, reports Kashmira Gander, there's a meeting where you can go and bear witness

We know the story: hard-up artists and bohemian types living by the pay-cheque settle somewhere cheap to live and create. Soon, the run-down hardware store down the road is an artisan cafe, and the corner shop is selling fixie bikes. Wealthier “pioneers” arrive, attracted by the vibe. Some time later, the bulldozers roll in to clear run-down social housing blocks and make room for luxury flats.

It’s gentrification, of course – a word coined in 1964 by the British sociologist Ruth Glass – and a story repeated so many times that its main characters have become figures of parody: the bearded hipsters disdainfully eyeing the uniformed young professionals, the second wave wanting to hang on to the area’s “authenticity” but eager to see a return on their properties – and somewhere a working-class family packing their bags to move to a cheaper neighbourhood.

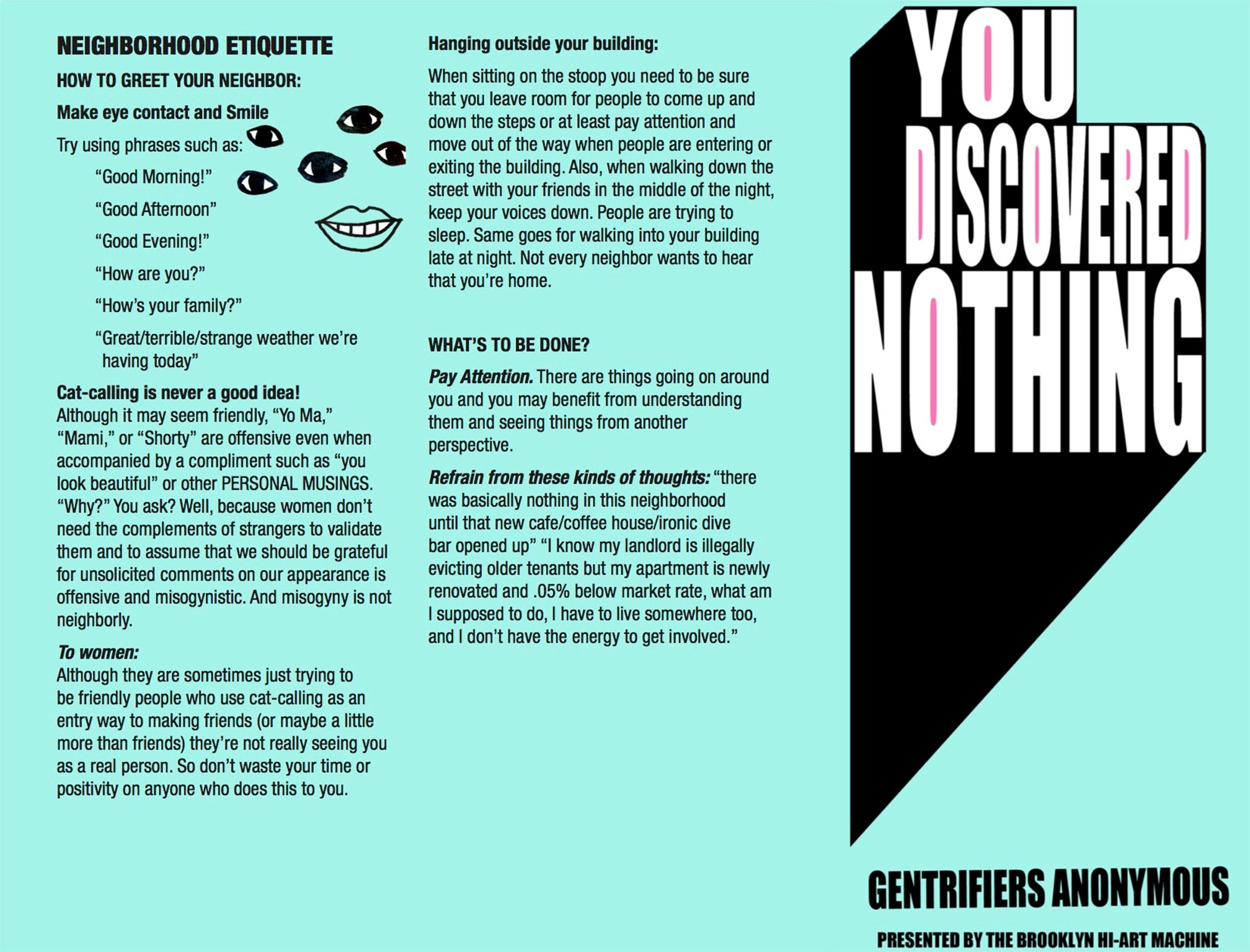

But must it be this way? In New York, an art group has at least been tackling the issue by inviting self-confessed improvers and members of existing communities to a 12-steps-style discussion circle dubbed ‘Gentrifiers Anonymous’. Organisers from the Brooklyn Hi-Art Machine and More Art want to give attendees the opportunity to explore if and how they are complicit in the adverse effects of the phenomenon.

And the effects do seem to be largely adverse. Although, in theory, affluent people moving into low-income areas creates mixed socio-economic communities, promotes entrepreneurial spirit and boosts schools – and who can deny that those fancy cafes sell some damn fine coffee? – many experts believe that gentrification, as opposed to regeneration, is bad by definition.

Loretta Lees, Professor of human geography at the University of Leicester, stresses that, while regeneration suggests an area is being spruced up without displacement, gentrification by definition means an influx of wealthier people who displace poorer or low income groups, and cites the Heygate estate in south west London as one of its starkest British symbols. Despite comprising structurally sound and spacious social-housing flats, the 1974 building was demolished 40 years later and its 3,000-plus residents made to move on, leaving behind their support networks.

Would a church hall meeting have helped? Well, according to Oasa DuVerney of the Brooklyn Hi-Art Project, “admitting you are part of the problem is the first step towards recovery and change”. DuVerney, a resident of Brooklyn, believes the problem partly lies in a lack of communication between those entering “new” areas and the working-class residents, who are also often from ethnic minorities.

In her own case, she says, “I’ve watched our neighbourhood in Brooklyn transition from buildings and storefronts neglected by landlords and city officials to a neighbourhood of rising luxury apartments, expensive eateries and bars that our community has been shut out from. The luxury apartment building on our block literally has a fortress built around it.”

However, she believes that gentrifiers can help to ease their impact by joining in with the existing community, rather than forming a parallel one. She argues that current attitudes simply aggravate the inequalities in society.

“This is the coloniser mentality that makes them [the gentrifiers] believe the destruction they are causing to the environment and other people’s communities is okay. They think the people already there aren't like them. They aren't really people who matter or who have worked hard enough, or tried hard enough; they haven’t wanted enough out of life to have the same success.” The incomers, she says, are the sort of people who might have used 2014’s controversial SketchFactor app – which allowed users to rate how “dodgy” an area was, according to how uncomfortable they felt (and drew accusations of racism as a result).

Professor Lees sees such attitudes reflected in the UK, where programmes such as Benefits Street have played into a notion of the “undeserving poor”. But for Dr Oli Mould, a lecturer in human geography at Royal Holloway University of London, the crux of the issue is social housing. “Simply put, any new development reduces the amount of social housing available. Until this ideological attack on council tenants abates, gentrification will continue.”

Is the solution, then, to leave low-income areas in a state of disrepair to deter the middle-classes? Not necessarily, says Jess Steele of Jericho Road Solutions, a south-coast organisation that aims to prevent gentrification by helping residents and businesses to regenerate their area while preventing displacement.

Based in the seaside town of Hastings – which has its fair share of both the down-on-their-luck and upwardly-mobile – its unofficial slogan is “Too late for Hackney, not yet too late for Hastings”. Steele and her team have raised funds to buy up Rock House – a 1960s office block which they have converted into a mixed-use creative space, as well as capped-rent flats – but she knows “it will never be enough to protect the neighbourhood, let alone change the world”.

Why? Because, as Dr Mould says: “The problem stems from underlying causes of putting profit and self-interest over communities and communal living. The gentrifiers can be on the local school board, organise charity drives and neighbourhood watches, look after vulnerable residents or create food banks. But until the prevailing forces of urban development stop being primarily focused on generating profit via the constant upgrading of land, then these goodwill gestures will be little more than froth.”

Professor Lees argues that a sense of defeatism is also part of the problem. “People have rolled over and they think they can't control any of this. They see the property market and the industry as so massive, they feel they have no control over it. It’s like a giant tsunami.” But again, for her, the only solution is to build more social housing.

As for the artists, they may believe that “sharing” in a meeting is a first step, but even they know the limitations: “We can talk in circles forever about all the different programmes that can be created to fight poverty,” says DuVerney. “But at the end of the day, if our governments continue to create it through the systematic exploitation of the poor, working class… to benefit a paranoid and greedy elite, then we’re all f*cked.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks