Generation Tate: How can we stop losing vulnerable men to the ‘manosphere’?

Try to ignore it all we like, but young men across the world are being seduced by the misogynist, conspiratorial teachings of influencers, writes Matthew Neale. Is early compassion the way to stop it?

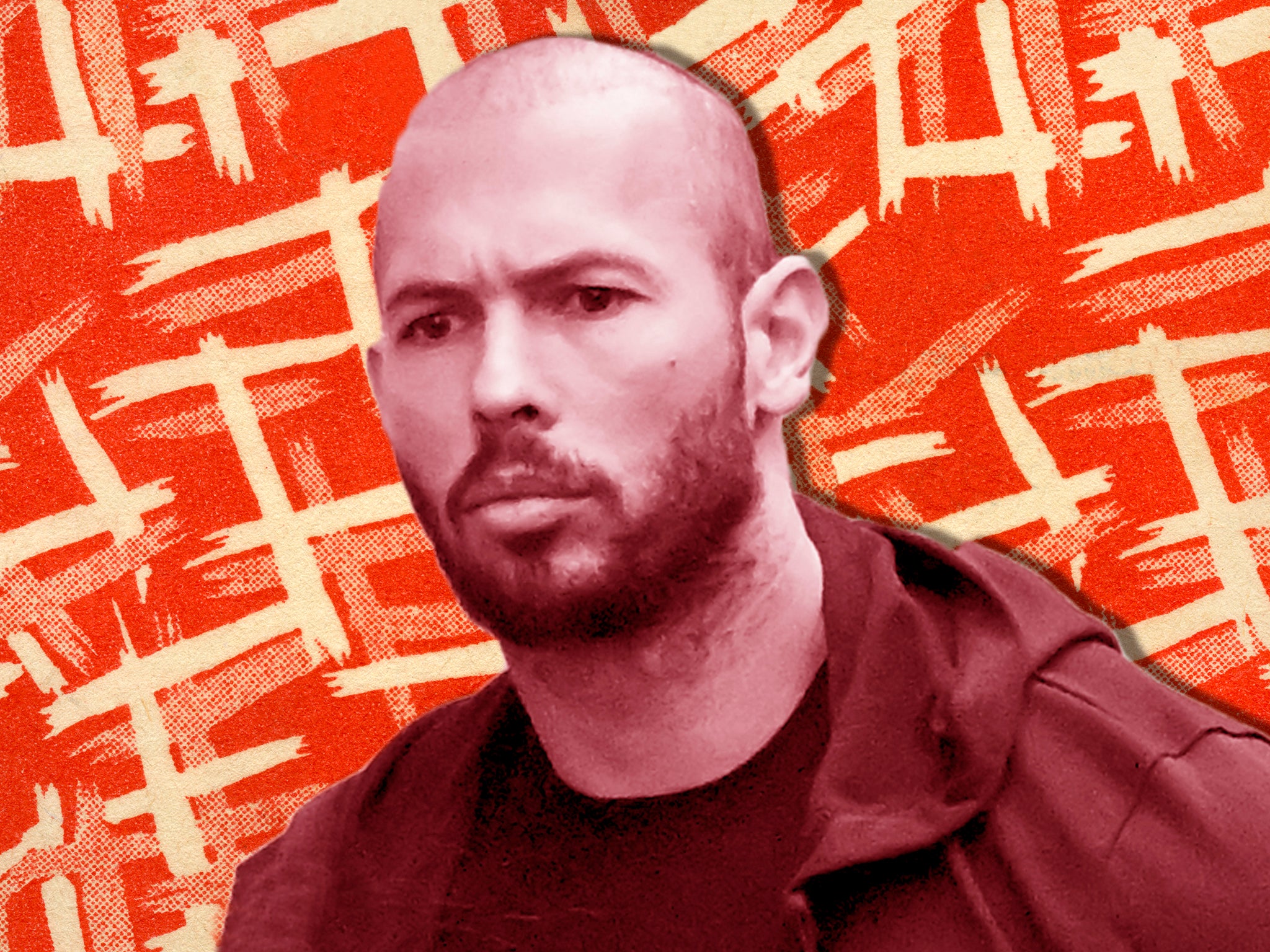

Unless you’ve been hiding under a pile of unrecycled pizza boxes for the past month, you’ll no doubt be wearily familiar with the name Andrew Tate. At the time of writing, the 36-year-old former kickboxer remains in custody in Romania, after being arrested alongside his brother as part of an investigation into human trafficking, rape and organised crime. But despite the horror of his alleged offences, it’s Tate’s public position as an influencer and internet personality that has sparked concern across the UK.

As far as both sexists and grifters go, Tate is audaciously honest about his game: as well as describing himself as “absolutely a misogynist”, he can also be found on camera admitting that the brothers’ webcam business – in which models take calls from fans in exchange for money – is a “total scam”. He claims that victims of sexual assault should “bear responsibility” for their attacks, that women are men’s property, and so on; views that are becoming so popular among boys that many schools are now hosting special assemblies to try and tackle them. In some ways this can be viewed as the endgame of the Trump era, where traditional right-wing dog whistles have been replaced with explicit calls to bigotry and violence.

Where Tate’s philosophy is more insidious – and where he arguably shares an allyship with other lifestyle influencers who might publicly baulk at the comparison – is in what it claims to offer the young men who encounter it. You know the one: the capitalist wet dream that tells men that they too can amass a collection of sports cars, supermodels and tedious podcast appearances if they just follow the advice of the magic bald man – at a price, naturally.

Ali Ross is a psychotherapist and spokesperson for the UK Council for Psychotherapy (UKCP), who often speaks to men struggling to find their place in the world. Despite the aggressive language of such influencers, he believes that what makes them so appealing to men isn’t just the invective, but the comforting message that sits at the heart of their narratives: it’s not your fault. “The reason why men connect with what people like Tate are saying is because they’re feeling disenfranchised and misunderstood,” he explains. “But like many men, they don’t know how to be vulnerable, how to review their choices or take responsibility for their lives.”

Even weapons-grade shade like Greta Thunberg’s isn’t likely to change the minds of their acolytes, but instead often reinforces the idea that the other side – in this case, essentially, left-wing women – are hostile and threatening. Whether the promise is money, fame or happiness, self-appointed “alpha male” influencers like Tate offer vulnerable young men a hand on the shoulder (“no homo, obviously”) when they perceive the Thunbergs of the world to be offering a barrage of slaps to the face.

When the thing you need most in the world is to hear someone say that they feel your pain, that becomes an addictive drug that influencers are keen to peddle. In fact, it’s essential for the scam to work. Ross explains: “When you have somebody saying, ‘It’s not your fault, it’s the system, men need to go back to their true primitive role,’ it invites the suggestion that there is certainty; that there’s something men are supposed to be and supposed to do.”

Being understood takes away some of that rage

Generational divide is a key storytelling facet of almost every corner of the “manosphere”, the loose web of right-wing, acronym-obsessed groups who oppose feminism and claim to advocate for men – these include MRAs (Men’s Rights Activists), MGTOW (Men Going Their Own Way), PUAs (Pick-Up Artists), and incels (involuntary celibates). As they tell it, men were once “real men”, who stalked the earth in an unspecified halcyon era of masculine dominance, chain-smoking cigars and coming home to subservient, family-oriented wives who also understood their place in the world.

While many men may feel confused about how to express their identity within the complex framework of masculinity today, the conservative fantasy that older generations were happy and secure in their roles remains a potent myth. “In fact, if you ask men of a generation or two further back who are willing to be open and honest, a lot of them didn’t actually have very happy relationships being in that clear fixed role,” Ross says. He cites Willy Loman, the protagonist in Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman, as an example of the lives that frequently played out behind closed doors: “He’s utterly miserable, but determined to be the provider, this embodiment of the American dream. And it’s killing him.”

Part of what can make MRA narratives so appealing is that they acknowledge the rates of depression, suicide and incarceration in men – figures which are real and terrifying – but then weave a fictitious global conspiracy around them. Tate occasionally talks, in paranoid terms, of “the matrix” coming to get him, implying an Illuminati-style conspiracy in which the world is neatly divided into heroic truth-tellers (such as the ones who throw money at bored-looking women in bizarrely low-budget rap videos) and the shady liberal elite who want to silence them.

With that in mind, the most powerful weapon in our arsenal remains our compassion. “That’s where therapy can come in so well: to help people recognise that uncertainty is a part of being alive,” Ross says. “You don’t have a role, and even if someone does prescribe a role to you, there’s nothing to say that’s going to fit you just because of your sex or gender. It is actually down to you, so let’s look at what you actually want for yourself.”

It’s also going to require men speaking to other men about their feelings, as daunting as that prospect may be. School interventions are a great idea, but maybe we need to be taking a more proactive approach to offer that hand on the shoulder from our educators – before the millionaire grifters get to them first. Let’s shout it louder, for the people at the back, that the patriarchy hurts men too, and the twin goals of feminism and men’s mental health can and should be working to uplift each other. They’re not in competition.

The battle won’t be won on the soft liberal platform of hugs and therapy alone. It’s vital that misogyny is called out and fought wherever it’s encountered, and not always in polite, hand-wringing niceties. But if there’s to be any hope of pulling young men back from the brink of perpetually viewing women as the enemy of their wealth and happiness, it’s going to take earlier and kinder interventions too.

“In being vulnerable with men as another man, it helps to show them that it’s possible to be emotional, and that there is something beautiful and courageous about being vulnerable, rather than believing you’ve got it all figured out and it’s just the system that’s not giving you the space to flourish,” Ross says. “Being understood takes away some of that rage; it makes them feel connected and even loved. I would like to think that when people experience love in the face of feeling overlooked or misunderstood, their venom dissipates.”

In other words, fighting fire with fire isn’t always likely to be effective, especially if they’re just as liable to end up conversing in a series of unimaginative memes. “Whereas if you meet them from a space of humanitarian compassion, that throws them off,” Ross continues. “It’s not a trick. That’s the beauty of therapy: it comes from a place of genuine compassion. And then by experiencing compassion for themselves, they start being able to see and feel compassion for others – including women.”

The Andrew Tates of the world proudly display their venom for all to see, but the reality is that the world is full of men looking to make a quick buck on the promise that Instagram-ready success is yours for the taking. The sooner we can start allowing all children to realise that their future happiness doesn’t need to be tied up with ludicrous Victorian-era gender stereotypes, the sooner we’ll stop losing men to hatred, bullshit lifestyle scams, and dressing like Pitbull.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments