Learn to Live: London children share tips on coping with stress and mental health with Iraqi pen pals

‘The children in Iraq and Stoke Newington will have had different experiences, but a child remains a child’

Schoolchildren in London and Iraq are sharing tips on how to cope with stressful situations as part of our Learn to Live campaign.

Pupils at Betty Layward primary school in Stoke Newington, who are given weekly mindfulness lessons as part of their curriculum, decided to write to the children they are twinned with in Iraq to share what they have learnt.

The pupils were among the first to be linked as part of our campaign with the charity War Child to better support children who have lived through conflict.

Since it started, more than 330 other British schools have signed up to twin with schools across the world.

Despite their very different backgrounds, the Betty Layward children have forged a bond with the Iraqi children, exchanging letters and videos, and sending instructions of how to play their favourite playground games to each other.

The latest step in their twinning journey is focussed on improving mental health and wellbeing.

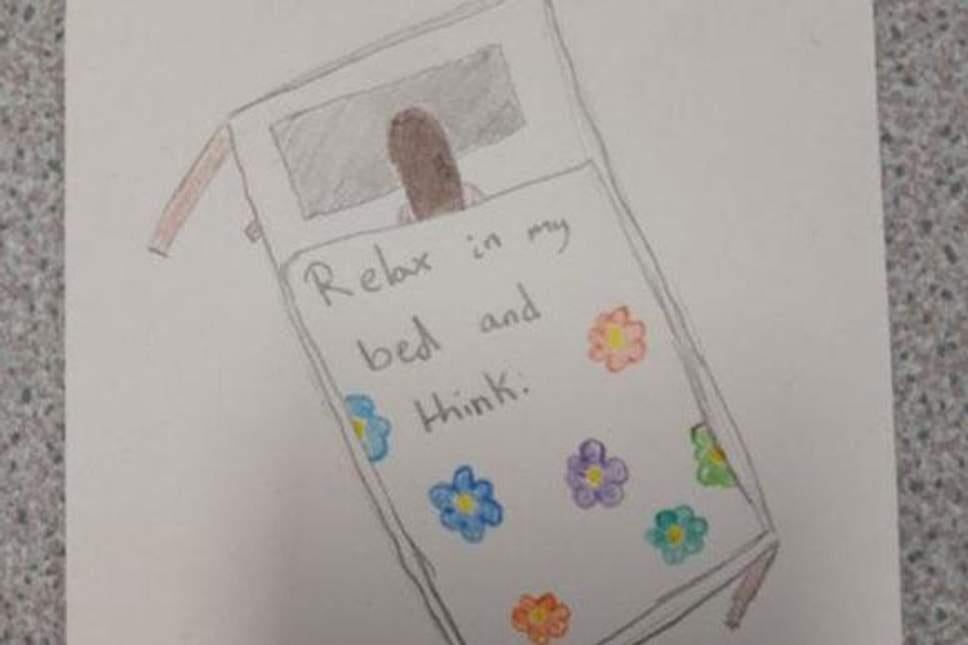

The Stoke Newington children described in pictures how they use “petal practice” to help them calm down – opening and closing their hand in time with their breathing. They also said they use the “finger breathing” technique – tracing their finger around their hand while breathing in time with their finger movement. They described how they play “pass the water” to build up trust with their classmates, where they sit in a circle with their eyes closed and pass a cup of water around.

The children in Iraq, who live in a displacement camp, participate in classes run by War Child and also undergo lessons about emotions and how to deal with them.

The classes focus on how to cope with life after armed conflict, and “dealing with emotions” is one of the modules.

We expect the children in Iraq to have some of the same kind of everyday worries, such as friendships and upsetting someone. But they will have other worries such as about safety. The important thing is that we talk about it

They plan to write back to their London counterparts to tell them what they learn and see if there is any common ground.

Betty Layward headteacher Jessica Bailey said: “The children have mindfulness lessons each week for a term. It is good to start them young, helping them to deal with difficult situations and being able to cope when something is hard.

“There will always be some point in your life which is hard for you.

“We say it’s OK to have a worry, but we need to understand how we manage them.

“We expect the children in Iraq to have some of the same kind of everyday worries, such as friendships and upsetting someone. But they will have other worries such as about safety. The important thing is that we talk about it.”

Clemence Muzard, programmes operations coordinator at War Child, said the “emotion classes” run by the charity focus on psychosocial support, and if a child needs intense trauma treatment that is dealt with separately. Consequently, the two sets of children may find they have similar worries. She added: “Definitely the children in Iraq and Stoke Newington will have had different experiences, but a child remains a child.

“We look at the difficult situations a child has been through and it doesn’t have to be about the war. They could have a father who is difficult with them or violent – and the same thing could happen to a child in the UK. It doesn’t have to be because they are displaced.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks