‘They have lost how to learn’: Uganda’s youth face uncertain future after world’s longest school shutdown

A lack of remote learning means returning pupils are playing catch-up, while millions of others are unlikely to go back to class because of economic hardship, reports Michael O’Hagan

Sitting in the shade outside his school in Kamuli Nalinya village, just northwest of Uganda’s capital, headteacher Freddie Mpiima is anxious as he reflects on the impact of the world’s longest Covid-induced education shutdown.

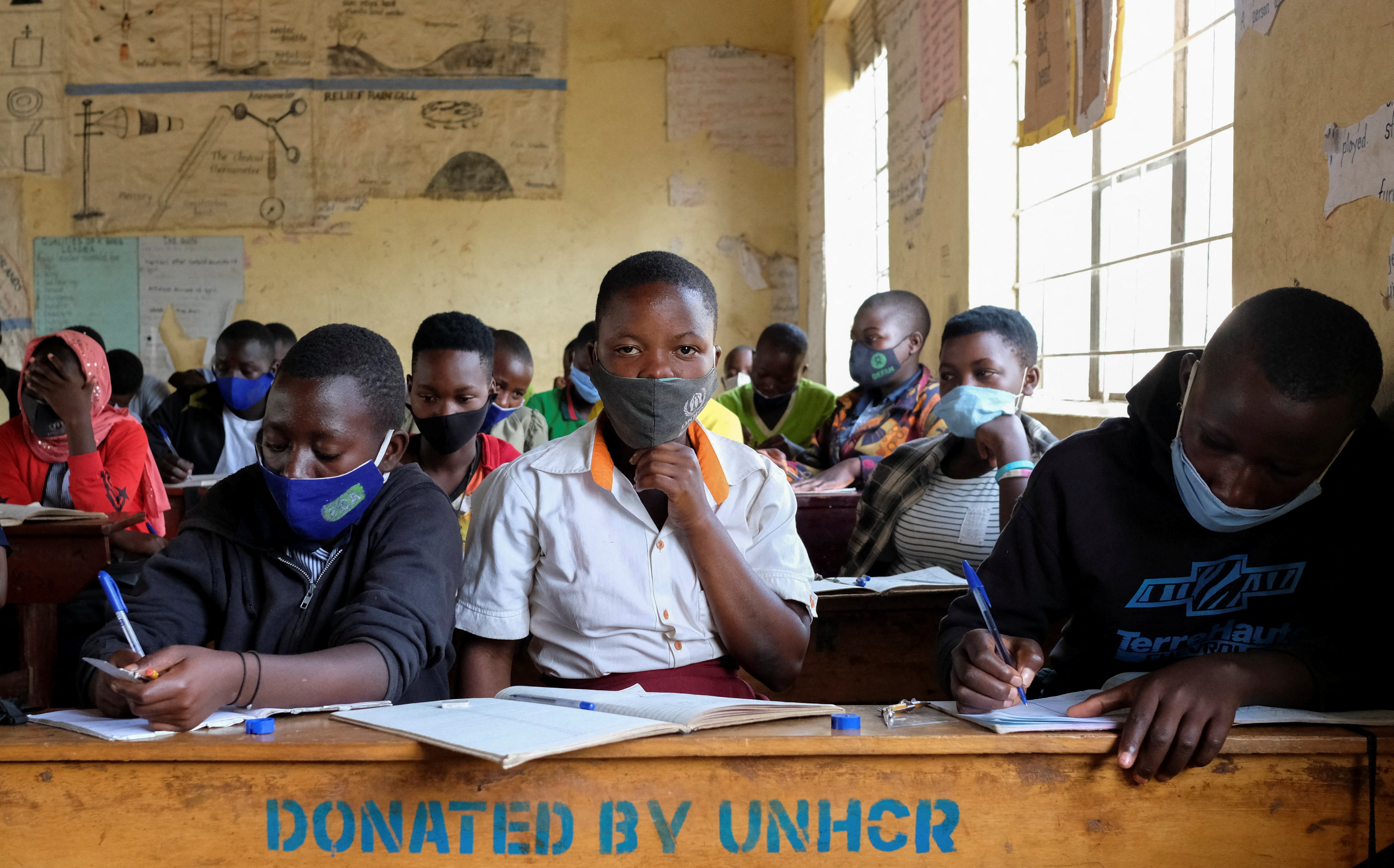

Schools across the east African country finally reopened on Monday after being closed for more than 83 weeks, affecting more than 10 million pupils, according to the UN.

Yet campaigners and officials fear that millions of children will not return to class because they are working to help their families, have fallen pregnant, or have been married off, while teachers are concerned about the lost learning time for those who are able to return.

“Children have lost so much,” Mr Mpiima, headteacher of Kizito Buzimba Primary School, tells The Independent. “They have lost how to learn.”

Fewer than half of the pupils who attended the school before the pandemic are back in the classroom this week, he adds.

Uganda’s national planning authority last year predicted that about 30 per cent of the country’s learners would never return to school, as a result of child labour, teenage pregnancies, and early marriage. About a tenth of schools nationwide – more than 4,000 – were expected to close permanently because of financial pressures.

Many teachers – especially those employed in Uganda’s large private sector – failed to report to work this week, having found better-paid jobs in other sectors, according to local media reports.

And while families around the world have struggled with home learning during the pandemic, communities in Uganda endured a particularly difficult time.

There is a huge risk that children may have lost interest in learning

Throughout the almost two-year shutdown aimed at curbing the spread of Covid, Ugandan president Yoweri Museveni and his wife Janet, who is the country’s education minister, pledged support, including printed learning materials and remote lessons that would be broadcast over TV, radio, and online.

When critics pointed out that many households do not own a radio, and that internet data costs are prohibitively expensive, the Musevenis – who have been in power since 1986 – vowed to distribute 9 million radio sets. The radios never materialised.

Mr Mpiima says that many of the parents in Kamuli Nalinya village are farmers who have never been to school.

“They can’t teach children to read. The village doesn’t have a reliable electricity supply, and maybe one household in 10 has a radio or TV,” he says. “So how could we do remote learning?”

With the support of the Save the Children charity, Mr Mpiima and parents from the school managed to provide children with a couple of hours of basic education each day in catch-up sessions.

One of the returning pupils, 13-year-old Hope Sagala, beams as she describes how the sessions kept her love of reading alive.

“The [catch-up] club gave me back that love of learning. I started reading more,” she says.

However, she says, many of her peers will not be going back to school.

“Some of the boys have got jobs ... on building sites. They have some money now but they’ll regret it,” she says.

“Some girls in the village have got pregnant. Their boyfriends tell them they don’t need to learn when they have rich men.”

Uganda reported a 23 per cent rise in pregnancies among girls aged 10 to 24 between March 2020 and June 2021, UN data shows.

Save the Children representative Edison Nsubuga says education is not just about learning, but providing a safe space for children.

“Some households were forced to send their children to exploitative labour such as agriculture, mining or trading on the street ... so there is a huge risk that children may have lost interest in learning,” says the charity’s education specialist.

“Before the pandemic we already had a huge learning crisis,” he adds. “We had children completing primary school without mastering the basics essential for life, and this has been exacerbated by this long absence from school.”

Despite the concerns of campaigners, the government’s minister for primary education is pleased with the return to school, saying on Thursday that between 90 and 95 per cent of the country’s learners would be back in class by the end of the week.

“So far, so good,” is minister Joyce Moriku Kaducu’s assessment in an interview with The Independent.

“It’s true this generation needs a lot, but it’s not yet out of control. It’s something we can manage collectively,” she says. “It’s easy to blame the government for anything that goes wrong, but parents have equal responsibility.”

One Ugandan student who particularly enjoyed the return to school on Monday is 18-year old Brennan Ekoyu, who has become something of a national celebrity for his viral TikTok skits mimicking teenage schoolgirls and female teachers.

While his feminine impressions drew some criticism online from socially conservative Ugandans, and sparked concerns that he might receive a hostile reception from his teachers back at school, the TikTok star’s mother says such fears have proved unfounded.

“To our surprise his teachers were very excited when we arrived at school with him,” Ann Apolot tells The Independent. “I could hear some of them saying ‘Welcome back our celebrity.’”

But most young people in Uganda are not so fortunate.

Covid closed so many things and people lost hope

Before the pandemic, 19-year-old Muhammed Asiimwe was a prefect at his school in Kampala, where he was captain of several sports teams and maintained good grades.

Muhammed had ambitions of going to university and travelling abroad – buoyed by a scholarship and charitable support that paid for his school fees and clothes. But the funding and help dried up when schools closed, leaving him stranded and hopeless.

“It’s difficult to study at home and I fell behind. Schools closing changed everything,” says Muhammed, who lives in Kampala’s Naguru slum in a one-room house with his elderly grandmother and 11 young siblings and cousins. His parents moved to Kenya to find work about a decade ago, and he has not seen them since.

Located in the shadow of luxury apartments inhabited by diplomats and UN officials, Muhammed’s neighbourhood is known as “Naguru Go Down” – a densely packed warren of cheap, tiny, ramshackle homes.

Since the pandemic and the school shutdown, the teenager has spent much of his free time building a hangout spot – made from scavenged pieces of wood – that he refers to as “Amazon”.

Many of the teenagers who relax there to escape the pressures of slum life have dropped out of school, and have no intention of going back. In a nearby building, other boys spend their afternoons getting drunk, or high. Muhammed says he tends to flit between the two groups.

“Covid closed so many things and people lost hope,” he says. “If guys can somehow make 200,000 shillings (£40) a month, they think going back to school is useless, which is not right.”

Over the past two years, petty crime has soared in Kampala, which was once renowned for being one of east Africa’s safest cities, and Muhammed says he and his friends needed somewhere they could stick together and stay safe.

“Naguru is one of the places where many of the kids are thieves,” Muhammed says.

“I have to stay disciplined and get back to studying,” he adds. “But after two years it’s not easy.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks