As Turkey’s economy reels, speculative traders and well-off insiders see opportunity to profit

State measures to prop up the lira have raised concerns of corruption as a sizable minority are believed to have emerged as financial winners from Turkey’s economic crisis, reports Borzou Daragahi in Istanbul

As most of the Turkish public saw their savings and purchasing power melt away, 40-year-old Tuna Ak closely watched the machinations of the United States Federal Reserve and Turkey’s Central Bank.

He bought up thousands of dollars in October when the lira was at nine to the dollar and sold it all when it reached 15 in December, turning a hefty profit, just before the Central Bank made a series of moves to boost the Turkish currency.

“I am following the news,” said the resident of Kocaeli, a father-of-two and a self-described jack of all trades.

“It was a very high number so I knew there would be an intervention,” he told The Independent.

An economic downturn has heightened inflation, increased unemployment, and crushed the dreams of millions of Turks.

Russia’s war against Ukraine is set to worsen the crisis by causing a spike in global food and energy prices and reducing crucial eastern European tourism that has been a steady source of income for the travel sector.

But Turkey’s decline has also produced some financial winners, raising questions and suspicions about the country’s economic rollercoaster ride.

Winners include quasi-day traders such as Mr Ak, whose ventures include buying and selling cars, olive oil, cargo shipping and cryptocurrencies.

Turkey’s high inflation rate of nearly 50 per cent benefits large debtors who took out massive lira-denominated loans when the lira was up, and now get to pay them back in currency worth a fraction.

The privileged few have made a killing

“The banks were able to borrow from the central bank and give it out as credit, sometimes to large construction companies,” said Ercan Uygur, a professor of economics at the University of Cyprus.

“They borrowed before the inflation jumped and at low-interest rates. And now they’re selling their products at higher prices. They’ve made a large profit.”

The huge profits come at the expense of savers and those with fixed incomes, whose salaries and nest eggs lose value, as well as taxpayers who are left holding the bill for massive government deficits.

“In the case of unexpected inflation those who lend are the losers, and those who borrow are the winners,” said Mr Uygur.

But there are also suspicions that some close to the government of president Recep Tayyip Erdogan benefited from insider information, particularly around a 20 December intervention by the state that sent the lira suddenly careening upwards after it was sliding downward in value against the dollar and other major currencies for months.

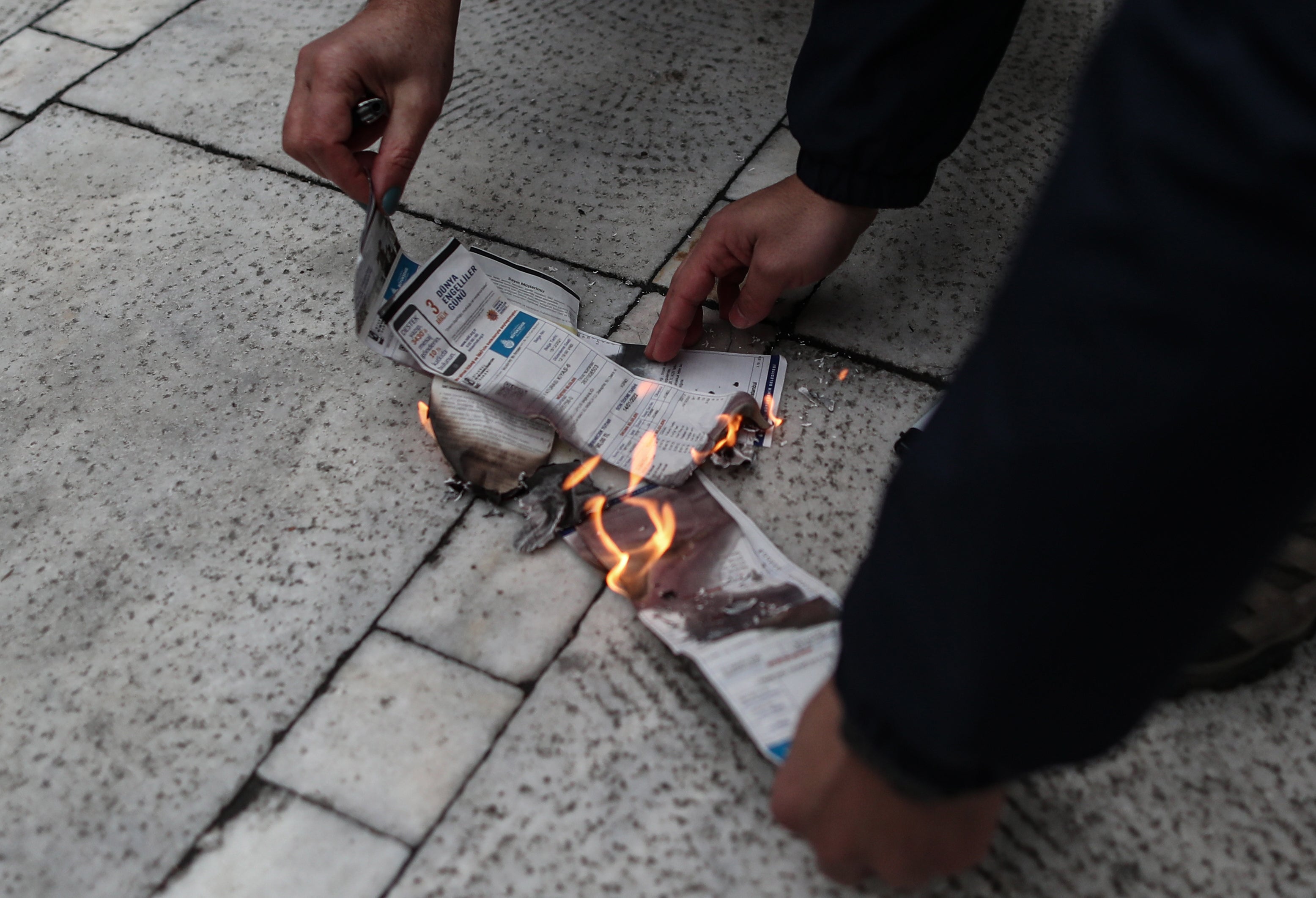

Turkey’s opposition People’s Republican Party (CHP) has asked for a probe into the matter.

Rejected by Mr Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party, which controls parliament, the CHP has launched its own investigation.

“It’s obvious that some people made a lot of money, and we are investigating that,” Ahmet Unal Cevikoz, a CHP member of parliament, told The Independent.

In particular, many people were irked by remarks by the country’s finance minister Nureddin Nebati after 20 December, in which he admonished those who did not follow the government’s counsel.

Some interpreted the remarks to suggest that big businesses close to the government would prosper while those that kept their distance would lose out, “that the people who meet with them and do business with them are able to profit”, as one senior opposition figure – who asked not to be named – put it.

Defenders of the government insist the comments were misinterpreted, and that Mr Nebati was only seeking to bolster faith in Mr Erdogan and his deputies. But many observers remain unconvinced.

“I think any member of the government, either the finance minister or the economy minister, are not convincing for the Turkish people any more, particularly after 20 December,” said Mr Cevikoz.

“The Turkish people, unfortunately, do not have trust and confidence in the cabinet any more. All the remarks that are being heard from ministers are met with suspicion.”

Ankara’s proponents claim that much of its problems stem from foreign investors sabotaging the lira to keep Turkey weak. Mr Erdogan has said the weakened lira will help transform the country into an industrial and export power.

There are other sectors of the economy that have performed moderately well. Thanks to the weakened lira as well as relaxed Covid requirements, Turkey’s tourism sector appears to have undergone a modest comeback.

The lira’s plunge has also drawn record numbers of international customers from Iran, Iraq, Russia and elsewhere buying up real estate and keeping property values somewhat steady.

And as the Russian war against Ukraine drives an ever-greater number of people from their homes, more of the rich from both countries could well be encouraged to purchase properties in Turkey that entitle them to visas.

But the unpredictability and volatility have hurt more mundane forms of commerce.

“Exports will be damaged in the long run,” said Gokce Gokcen, a CHP member of parliament specialising in economic matters. “The exchange rate is fluctuating so much that buyers and sellers cannot agree on a price. Goods are available, but companies are reluctant to sell them.”

Turkey’s economic boom of the 2000s was led by export growth and manufacturing that created good jobs. The now dimmed prospect of European Union membership drew foreign investment in labour-intensive sectors such as automotive and textiles.

But many analysts worry the current economic situation is luring entrepreneurs away from such endeavours and toward parasitic financial speculation, the same way America’s General Electric and General Motors began playing with money instead of focusing on inventing great products.

Turkish economists and political insiders describe a group of perhaps 500,000 or a million people who are in a position to spend their days on their phones, following currency fluctuations and placing buy and sell orders, milking ties for insider information.

“The people who are making money are not the ones who have any real economic activity such as commerce or manufacturing,” said Selim Sazak, a spokesperson for the opposition Iyi Party. “This class of money-holders, mostly upper-middle class, are people with money in the bank and connections. That privileged few has made a killing.”

Mr Ak admits that he did well for himself and his family over the last couple of years. But he acknowledges that he is a unique breed. He said he is now disturbed by the widening gap between rich and poor in Turkey, and how those making minimum wage are barely able to pay their bills, often forced to take out loans and accumulate debt that they can hardly hope to pay off.

Few people, he concedes, could thrive doing what he does.

“I think it requires a special kind of character,” he said. “Not everyone can do this. You have to have an open mind and be open to new ideas. I work in commerce and so I have this disposition. Most people are in search of an average job working 8 to 5 or whatever the hours are, and just looking to get by.”

Naomi Cohen contributed to this report

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments