In teargas we trust: How a chemical weapon is being increasingly used against peaceful protesters without scrutiny

Little is known about the companies that produce the weapon, what chemicals go into it and how they are used once they are abroad, Borzou Daragahi reports

Cat Villiers was living in the Egyptian capital making a feature film when she got caught up in the fiery protests that followed the 2011 Arab Spring uprisings. Repeatedly she found herself in the middle of demonstrations where police fired volleys of teargas into crowds. Day after day, she inhaled the searing vapours, the sharp smell permeating the walls and alleyways of her central Cairo neighbourhood.

That’s when she says the medical problems began. A lifelong sufferer of asthma, the frequency and severity of her attacks escalated. Serious respiratory infections sent her nearly monthly to the hospital in Cairo and back home in London. To this day, she continues to suffer bouts of illness she’s convinced stem from repeated inhalation of teargas.

“Slowly, during 2011 and 2012, I realised that my lungs were getting worse and worse,” said the filmmaker, who is now in her 50s and living in the UK. “After being exposed to it a lot, my chest complaints and propensity to get pneumonia got much worse. And it has remained like that ever since.”

In recent weeks, the role of teargas as a tool of law enforcement has come under scrutiny after security forces in the United States used it aggressively in failed attempts to suppress protests against systemic racism and police violence.

Police in Hong Kong have also been using teargas in their arsenal of “non-lethal” weapons against largely peaceful pro-democracy protesters opposed to Beijing’s attempts to bring their former colony more firmly under its grasp.

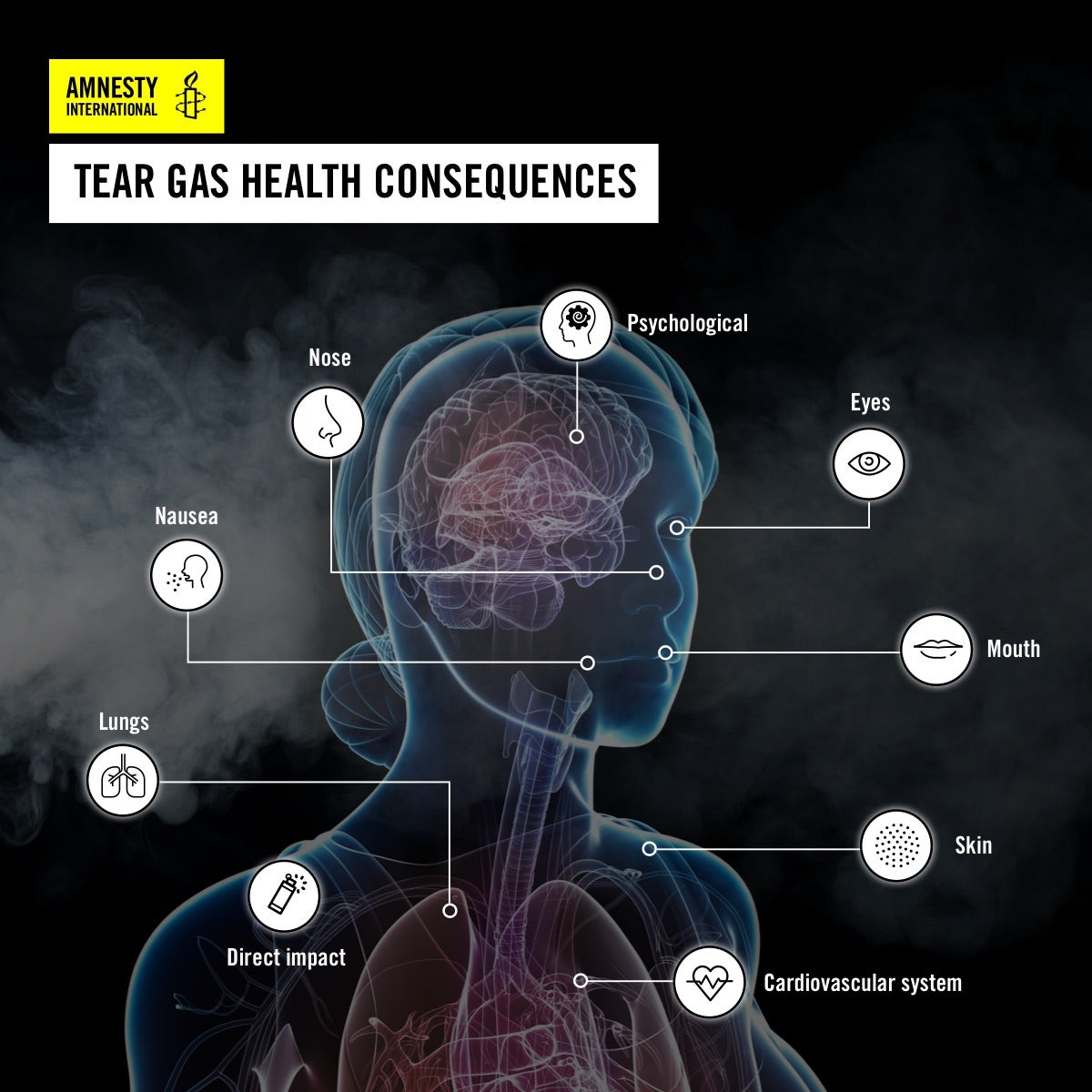

But despite its widespread and some say growing use, little is known about the companies that produce teargas, what chemicals go into it, and how they are used once they are abroad. Although considered non-lethal, medical experts say it is dangerous, and the US Centres for Disease Control (CDC) has warned that exposure may cause blindness, glaucoma and death because of chemical burns to internal organs or respiratory failure.

Those who have ingested teargas describe burning, painful sensations all over the face, extreme difficulty breathing and an inability to see that is felt acutely for around 15 minutes but lingers sometimes for hours. In some instances during the uprising in Egypt, intense use of teargas was suspected in the suffocation deaths of protesters.

“It’s definitely a weapon and once you give the police force a weapon they can misuse it,” said Patrick Wilcken, a researcher at Amnesty International, which is releasing a report on teargas today on the one-year anniversary of the uprising in Hong Kong. “And it’s a powerful weapon.”

Teargas was first used along the front lines of the First World War, and though it is now almost exclusively used as a law enforcement tool, the Netherlands-based Organisation for the Prevention of Chemical Weapons continues to define it as a potential tool of warfare.

As part of Amnesty’s project, it reviewed nearly 500 video clips of teargas used by security forces across the world. It concluded that use of the weaponry is increasing, with peaceful protesters targeted in residential neighbourhoods where inadvertent passersby inhale fumes.

What’s more, according to the report, police are engaged in “widespread” abuse of teargas by firing it into crowds stuck within confined areas that lack exit routes. Teargas is being fired near or even inside hospitals with vulnerable patients. Even worse, sometimes teargas launchers are used like guns, with canisters fired at 400 metres per second or 900mph, about half the speed of a bullet from a firearm.

Amnesty warned last autumn that Iraqi security forces seeking to quell anti-government protests were using military-grade teargas canisters that in several instances had shattered the skulls of unarmed demonstrators.

“It’s a high-velocity weapon that if pointed directly at people may cause serious injury,” says Mr Wilcken.

Every aspect of teargas – from the chemical cocktails used, to the ownership of the companies manufacturing it, and the global trade in the products – remains largely a mystery.

“There’s a complete lack of transparency of who is producing, how much they’re producing and where they’re exporting to,” says Mr Wilcken.

Requests for comment from several large teargas manufacturers including Combined Systems in the United States and Condor Non-Lethal Technologies in Brazil were not answered.

A few large companies worldwide produce teargas, many of them clustered in Pennsylvania. But many are smaller, even fly-by-night operations. Though teargas targets some of the most sensitive organs of the human body, there is no regulation of the chemicals used. Amnesty says the concentrators of the compounds used varies, and firms are not required to list ingredients.

“There is almost no transparency in the teargas production industry, and so little is known about what exact chemical combination is present inside each brand of teargas canister,” said the report.

Teargas is meant to be used as a drastic measure to disperse a crowd that poses a danger to itself and others. But police in autocratic regimes across the world often fire teargas indiscriminately at the start of peaceful protests as a way to suppress civil gatherings. Police in Istanbul, for example, fire as unarmed protesters gather to march peacefully for LGBT+, women’s or labour rights along public streets.

Most democratic countries producing teargas implement some type of export control on manufacturers to make a show of not allowing products made within their borders to be used to suppress democracy movements abroad. In the United Kingdom, campaigners and members of parliament recently called to restrict the export of riot gear, including teargas, to the US, for fear police forces were abusing it against peaceful demonstrators – including a group gathered near the White House that was violently dispersed when Donald Trump sought to pose with a Bible at a nearby church.

But Amnesty’s Mr Wilcken described several workarounds. In one case, a Brazilian firm pressured over exports to Venezuela simply moved its exports to a subsidiary company. During the protests in Egypt a decade ago, security forces used teargas, including some manufactured in the UK, that were past their expiry dates, suggesting that Egyptian authorities were either purchasing lots off the black market or using old stock.

Amnesty said it reached out to seven companies asking for contents of teargas and measures to prevent human rights abuses, such as use of teargas against children. Only one American firm replied, saying it exported only to countries permitted by the government.

“Companies also have a responsibility to make sure they are not complicit,” says Mr Wilcken.

Last year the Whitney Biennial, a major New York art event, forced the resignation of its chairman Warren Kanders, CEO of teargas maker Safariland, following protests by artists and activists.

But a host of smaller companies are less susceptible to public pressure.

Unlike makers of fighter jets and battleships, teargas makers operate on a smaller scale. The teargas industry likely is valued in the hundreds of millions of dollars, as opposed to the billions that trade hands in big defence deals.

Despite the health consequences on individuals and the increasing damage it does to struggling democracies, the industry and its actions are rarely discussed by lawmakers who scrutinise other defence deals.

During her years in and out of hospitals, Ms Villiers met one physician who believed her theory that her medical condition had been made graver because of teargas. Studies of US soldiers exposed to teargas showed that even young and healthy men “developed a high risk of presenting with acute respiratory illness” after exposure. But the doctor told her he would need proof. He drew up a proposal to conduct a comprehensive study of the impact of teargas on civilians, by examining people like Ms Villiers. But no one would fund it, she says.

“There’s an incredible lack of education within security forces and among authorities about teargas,” she says. “Or, it just may be disregard.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments