Sudan on the brink as PM’s resignation stirs fears of return to authoritarian rule

The sudden departure of Sudan’s prime minister spells trouble for the country’s political transition and protesters fear a backslide to decades of dictatorship, reports Ahmed Aboudouh

The resignation of Sudan’s Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok after another round of protests could prove terminal for the country’s planned transition to democracy, and has raised concerns of a return to authoritarian rule just years after the toppling of former dictator Omar al-Bashir.

In the latest rallies on Sunday - in the capital Khartoum and other cities - gunfire and tear gas filled the streets while three protesters were reportedly killed. For many demonstrators - who were marching against a 25 October military coup and ensuing power-sharing deal between Mr Hamdok and the army - the protests are a reminder of the 2019 struggle to oust Mr Bashir.

The October coup saw Mr Hamdok deposed and placed under house arrest as the army - led by Abdel Fattah al-Burhan - seized power and lurched Sudan back into the dark days where the military exerted control over every aspect of their lives for decades.

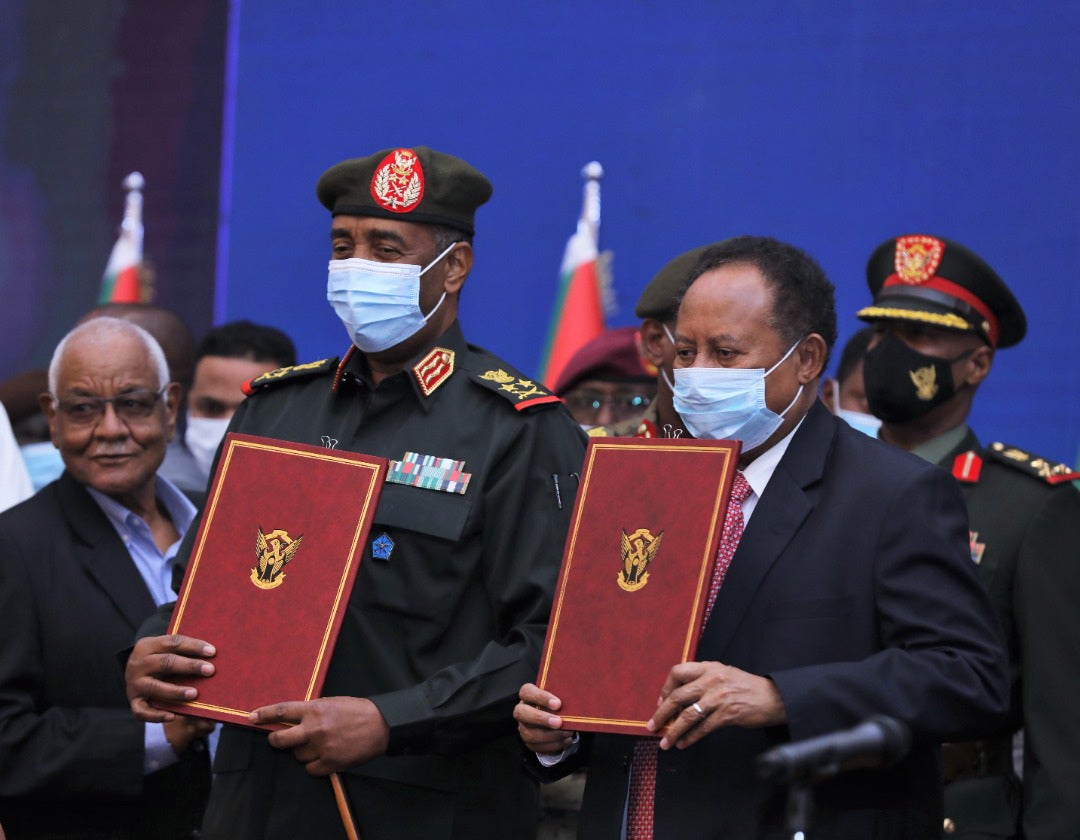

On 21 November, the military signed a deal with Mr Hamdok to form a technocratic government under military oversight – a move rejected by pro-democracy parties who have demanded a full handing over of power to a civilian leadership.

The latest protests proved the final straw for the prime minister, who resigned on Sunday night and warned that Sudan was now at a “dangerous crossroads threatening its very survival”.

His departure has left the military leadership to contend with pro-democracy protesters, political opponents whose leaders were sidelined in the coup, and some former rebels from the Darfur region.

“By shooting and repressing peaceful protestors, the military and security forces apparently hope to deter political demands for them to leave the commanding heights of the economy and to face accountability,” said Gerrit Kurtz, a non-resident fellow at Global Public Policy Institute - a think tank in Berlin.

But as military leaders elsewhere in the Middle East have proved since the 2011 Arab Spring uprisings, fear over democratic change that could shake the army’s control on power has defined the reaction of many Arab generals.

In Egypt, the toppling of the Muslim Brotherhood president Mohamed Morsi in 2013 by general Abdel Fattah el-Sisi reinstalled the military dominance over civilian technocrats with no meaningful authority – a tradition that dates back to the first army power grab in 1952.

In Sudan, generals have also chosen to install a technocratic cabinet to handle the chronically crumbling economy and deep-rooted social issues.

Even under the 30 years of Bashir’s regime, the military and the Rapid Support Forces, a paramilitary force led by the notorious general Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, known as Hemedti, enjoyed oversight over large parts of the economy, such as gold mining, while technocratic governments left grappled with the economic day-to=day problems.

“Probably, they are going to appoint a puppet prime minister and a government of technocrats with specific tasks. They will then hold early elections similar to the Egyptian scenario,” said Mohamed Abdelaziz, a Sudan-based political analyst.

According to the 2019 Constitutional Declaration, which set in stone the power-sharing deal between the military and civilian leaders and was seen as a roadmap towards democracy, the next prime minister should be appointed by a legislative council that has not been established.

By delaying the legislative body and excluding their opponents, experts suggested that Mr Burhan and the military leadership were on a mission to restore the Bashir-led order.

The situation could end up being worse than the Bashir era

“There is nothing to indicate that the military and the coup leaders have any clear goals beyond preserving their autonomy and impunity, which means restoring the pre-2019 status quo ante,” said Yezid Sayigh, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, a think tank.

“That is, they want much of what they had under Bashir, but in a post-Bashir era. This agenda suggests that Burhan and his allies have no idea of what to do next, beyond surviving from day to day.” he told The Independent. “Consequently, Burhan and his allies are heavily dependent on inventing a civilian facade for themselves, in the form of a new government.”

The military putsch and the November agreement with Hamdok were neither successful in extinguishing the street marches that have rumbled on since 2019 and been spearheaded by the Resistance Committees, a rising grassroots movement, nor did they convince the international community to maintain the initial economic support for Sudan.

Bashir’s regime had long been under crippling US sanctions but, with Mr Hamdok’s government in power, Washington removed Sudan from its ‘State Sponsors of Terrorism’ list.

Sudanese activists have not been deterred by the security forces’ increasing use of violence, mass arrests of their leaders, and repeated internet shutdowns to cut them off from the rest of the world.

On the other side, the Forces of Freedom and Change, the pro-democracy coalition and party to the 2019 power-sharing agreement, remains fragmented and unable to agree on a scenario for the future.

The street pressure on the military leadership and frictions within the civilian parties seem to have forced both sides into a standoff.

The generals’ relative weakness in the face of relentless protests, in particular, gives leverage to the US, the UK and other western countries who are pushing for a political settlement in Sudan, experts said.

“The violent crackdown and Hamdok’s exit make it unlikely that the coup leaders will succeed in persuading the Sudanese public or Western donors and international financial institutions to go along with those tactics and support a government under military tutelage,” Mr Kurtz said.

To escape the corner they found themselves in after Mr Hamdok’s resignation, the Sudanese military may resort to tactics used by the Algerian army to face the country’s 2019 uprising by “sitting things out until the opposition tires or fragments,” according to Mr Sayigh.

This would follow in the footsteps of their Egyptian counterparts by including their right to shape politics in the constitution while pulling back to leave daily governance to politically powerless civilian ministers, Mr Sayigh added.

But fears within Sudanese society remain over the risk of complete disintegration, as Mr Hamdok alluded to in his final statement.

“The situation could end up being worse than the Bashir era,” Mr Abdelaziz said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments