The diplomatic row which could prompt Europe’s next migrant crisis

A Western Saharan independence leader will appear in a Spanish court on Tuesday. The outcome of the case could see another humanitarian emergency emerge, reports Graham Keeley in Madrid

Hiding out in an old cemetery, a disused prison or in the hills in Ceuta, hundreds of children are trying to avoid being sent back from Spain to their old lives in Morocco.

They are the last of the children who flooded through the razor wire security fence or swam round into Spain’s North African enclave from Morocco two weeks ago.

Morocco stands accused of letting about 8,000 would-be migrants into Spain because of a diplomatic dispute which comes to a head on Tuesday, when a Western Saharan independence leader is due to give evidence via video link to a Spanish court.

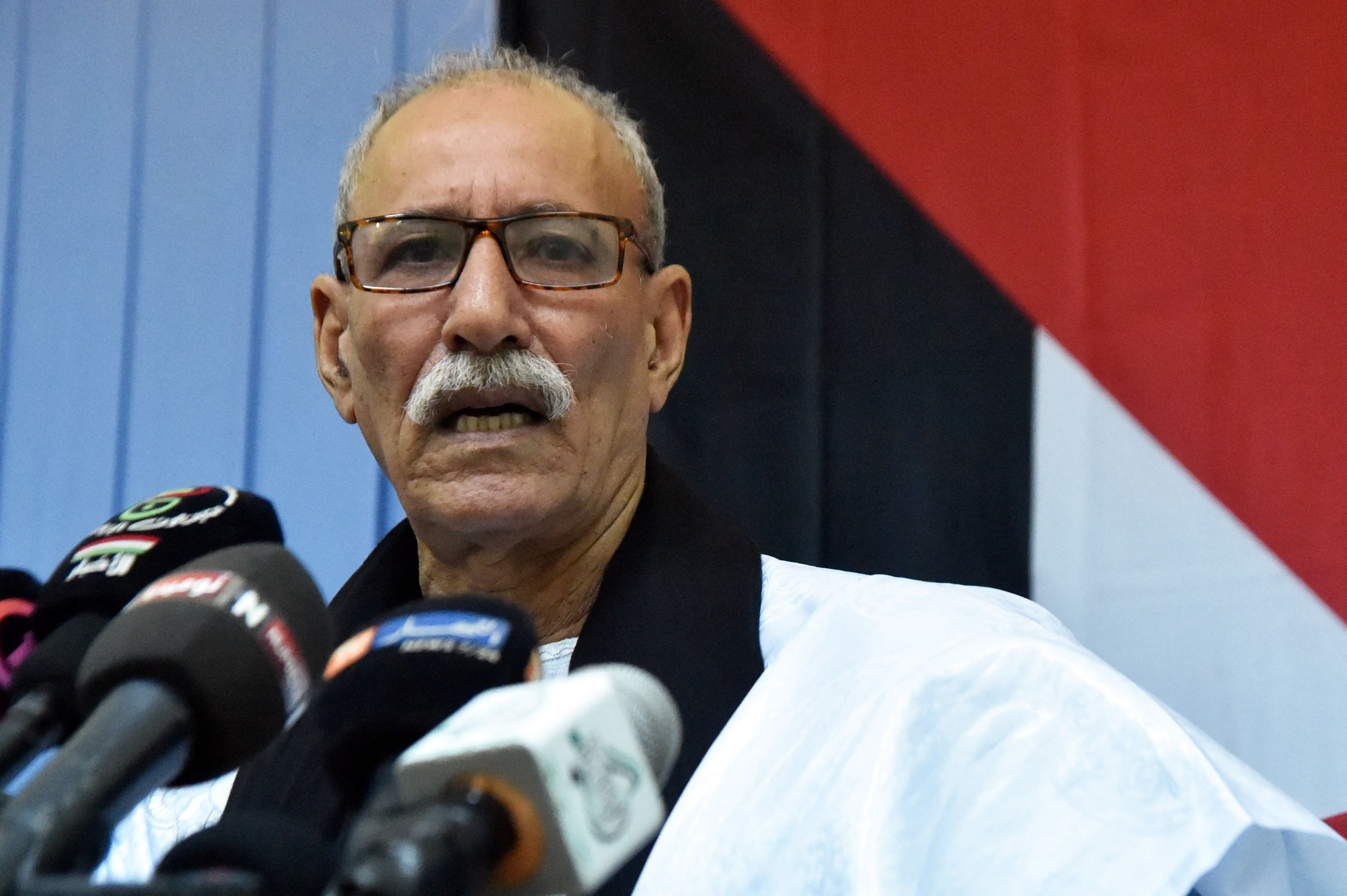

Brahim Ghali, the leader of the Polisario Front, stands accused of a series of offences including torture, genocide, murder, terrorism and disappearances, by Western Saharan dissident groups.

The 71-year-old will give evidence from a hospital in Logroño in northern Spain, where he has been treated for Covid-19 but is also rumoured to be suffering from cancer.

The outcome of the case may decide the future of the worst migration crisis on Europe’s border this year.

Ghali’s arrival in Spain using a false name and an Algerian diplomatic passport, sparked the most serious diplomatic dispute between Madrid and Rabat since Morocco invaded the tiny uninhabited Spanish island of Perejil in 2002, prompting Madrid to send in troops to reclaim the unknown speck in the Mediterranean.

Infuriated by Madrid allowing Ghali into Spain, Moroccan border guards looked the other way to allow children – some of whom were told they were on a day out from school or could get the chance to watch the footballer Ronaldo play – to surge through the border.

Spain’s foreign minister Arancha González Laya insisted Madrid allowed Ghali to be treated in hospital as a “humanitarian gesture” but he must answer charges in a Spanish court.

The Spanish government estimates 1,500 children made it to Ceuta but hundreds still remain, aid workers say, as authorities try to reunite them with their parents on the other side of the heavily fortified border.

Sabah Hamed, a Spanish businesswoman who lives in Ceuta, opened her house to offer the children food, clothes and showers.

Working with other volunteers and the Red Cross, she tries to calm the nervous children.

“The house of my father has always been one for refugees,” Sabah, a Spaniard who grew up in Ceuta, told The Independent in a telephone interview.

“When so many people arrived, I got lots of pasta to provide them with some food. What struck me most was the situation of the children, not only their physical state but how hungry they were.”

She added: “I don’t know what is going to happen to them but for now we can at least do something to help.”

She related the story of Baghi, 17, who spent days hiding in a hill overlooking Ceuta, one of two small Spanish enclaves which border Morocco (the other is Melilla).

“He saw that the border was open on Facebook and he asked if he could borrow €5 from his mother, then just left,” Sabah said.

The children still inside Ceuta face an uncertain future.

However, for Aschraf Sabir his dream of escaping desperate poverty in Morocco is over – for now.

Harrowing pictures of Aschraf crying as he swam the Mediterranean held up by plastic bottles strapped to his body moved many around the world.

“Try to understand us – we don’t want to go back,” the 16-year-old pleaded with Spanish soldiers who captured him when he reached the Ceuta beach during the huge influx of migrants.

Aschraf, who was abandoned by his mother three days after being born as she was only 16 and unmarried, was returned to live with his adoptive mother, Miluda Gulami, in a two-bedroom house in Casablanca.

After he ran away from home in February, Miluda filed a complaint after he went missing but heard nothing until she saw him on the news two weeks ago.

“I thought he was dead. But I later saw the video and I was very happy,” she told El Pais, a Spanish newspaper.

Spanish prosecutors have launched an investigation into the circumstances of Aschraf’s return to Morocco after a complaint by Coordinadora de Barrios (Neigbourhood Coordinator), an organisation which campaigns against social exclusion.

The group claims that the Spanish authorities did not consider Aschraf’s legal rights before he was speedily returned to Morocco.

Spain does not normally expel children without checking if they are in a vulnerable situation or if their parents were searching for them.

However, after the huge influx of migrants into Ceuta, Spanish prime minister Pedro Sanchez said there would be a rapid expulsion of young migrants according to the terms of a deal with Morocco, which was supported by Spain’s constitutional court.

Meanwhile, the political row over how Morocco apparently allowed thousands of migrants to breach a European border shows no sign of letting up.

Spain’s defence minister Margarita Robles condemned Morocco's use of young people to violate Spain’s borders.

"One thing is clear: when minors are used as an instrument to breach Spain's territorial borders, this is unacceptable," she told RTVE, Spain’s public television, at a military ceremony on Saturday.

Morocco pins the blame on Spain for welcoming an independence leader it has condemned as a “war criminal”.

“The real cause of the crisis is Madrid’s welcoming of the separatist leader of the Polisario militia, under a false identity,” Moroccan foreign minister Nasser Bourita said.

Analysts suggested that after exerting pressure on Spain by opening its borders, Morocco may now refuse to cooperate with Madrid on anti-terrorism policy.

“Morocco wants to change Spain’s policy on Western Sahara. That is its goal,” Ignacio Cembrero, a Spanish journalist who has written widely on Morocco, told The Independent.

Spain maintains the United Nations should broker a deal to end the conflict over Western Sahara, which was a Spanish colony until 1975.

The UN refers to Western Sahara as a “non-self-governing territory” whose people “have not yet attained a full measure of self-government”.

After 16 years of war, Rabat and the Polisario signed a ceasefire in 1991, but a UN-backed referendum has never materialised.

Hostilities resumed in November when the Polisario, which is backed by Algeria, declared the ceasefire to be over after Morocco sent troops into a UN-patrolled buffer zone to reopen a key road.

Madrid agreed to receive Ghali as a favour to Algeria, its main supplier of natural gas, according to reports in Spain.

The septuagenarian independence leader faces allegations of torture at Sahrawi refugee camps in Tindouf, a town in western Algeria in a case brought by a Polisario dissident Fadel Breika.

The second probe relates to allegations of genocide, murder, terrorism, torture and disappearances made by the Sahrawi Association for the Defence of Human Rights (ASADEDH), which is based in Spain.

Ghali denies any wrongdoing.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks