A coed accused a beloved college football player of rape. His teammate put his career on the line to support her

Betsy Sailor was raped while studying at Penn State in 1978 – and investigations resulted in charges against one of the school’s football players, a stranger to her. A new film documents how a teammate believed the young coed and became her advocate and protector, writes Sheila Flynn

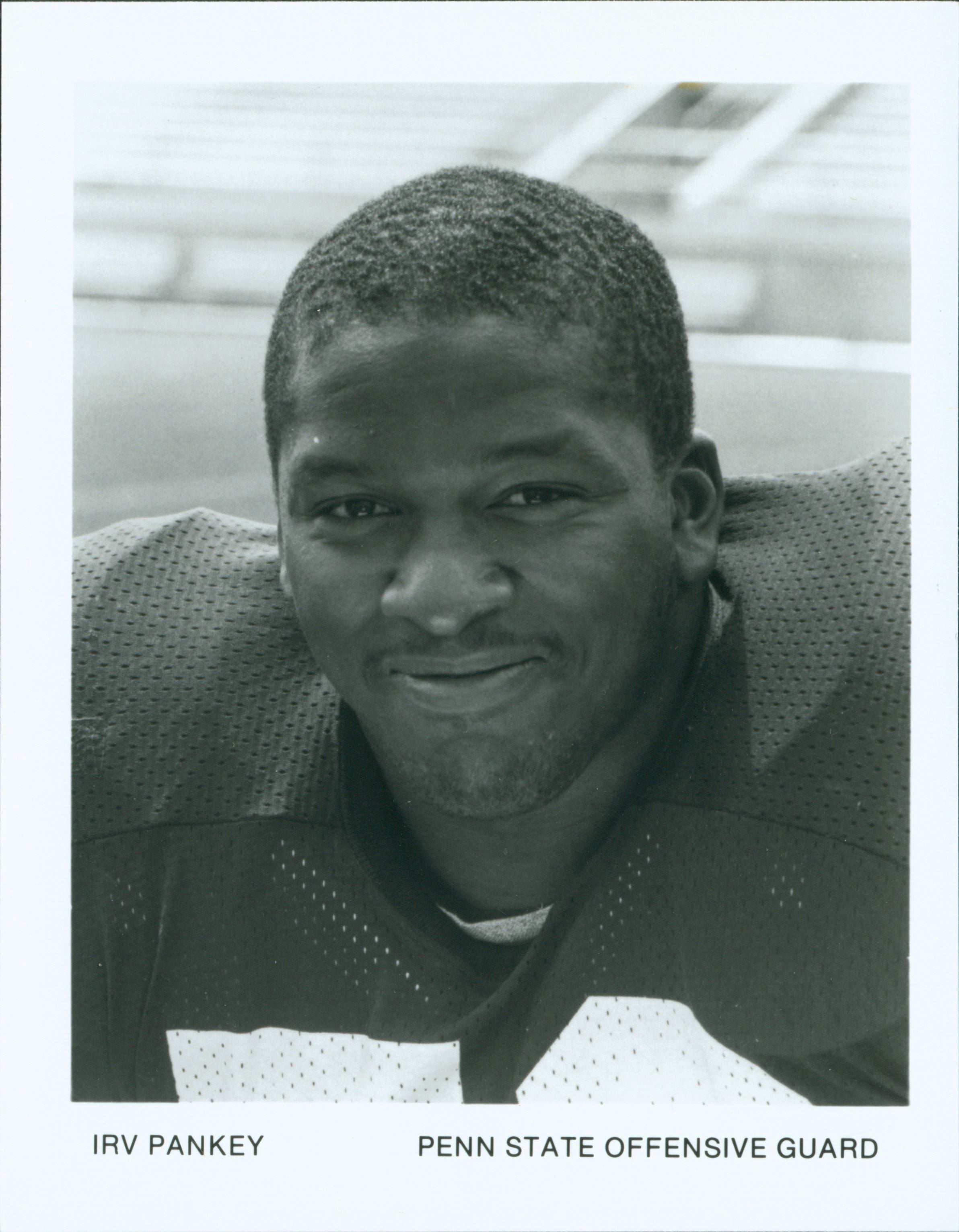

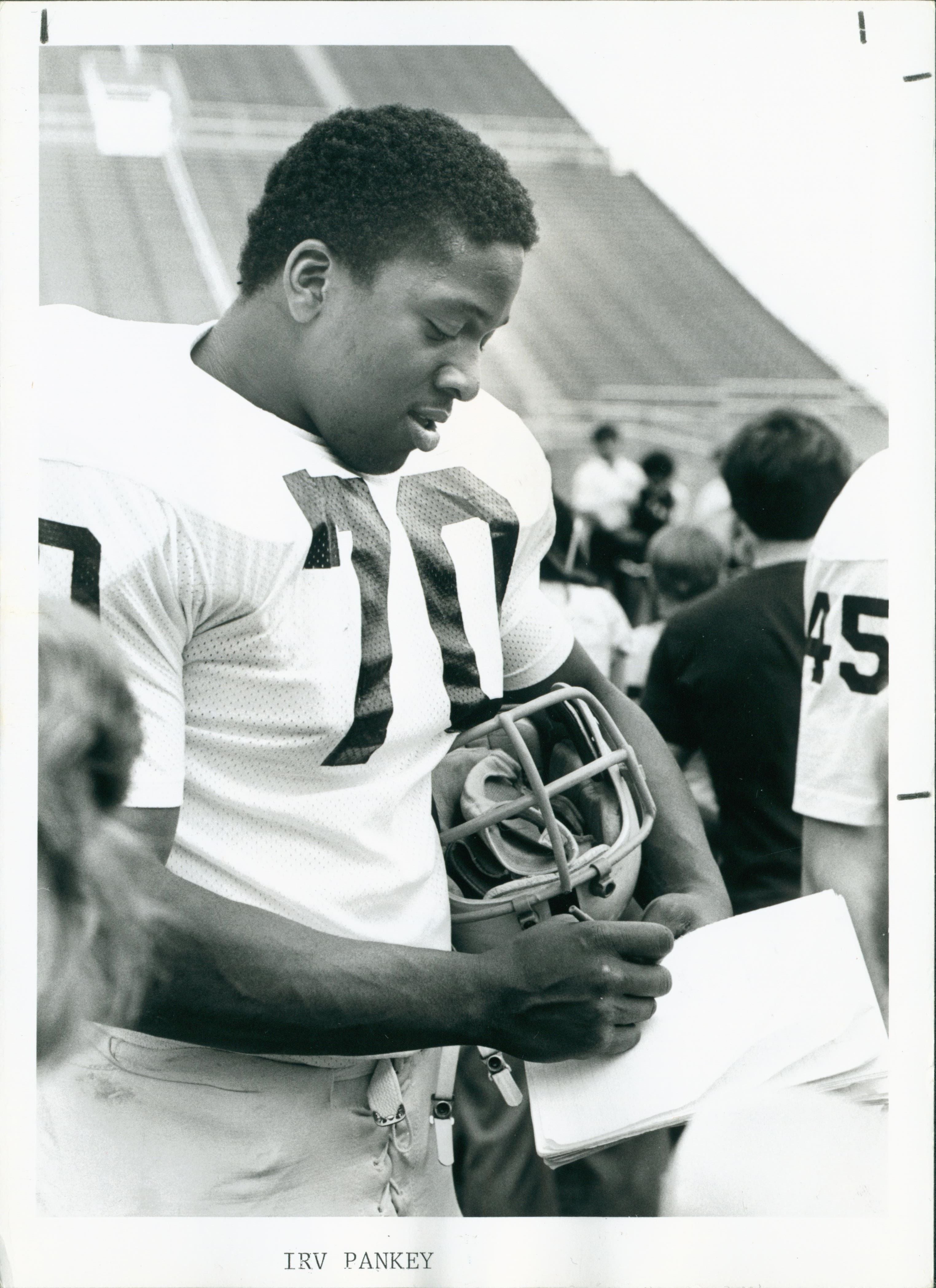

It’s still unusual now, and it was virtually unheard of back then – but, then again, neither Betsy Sailor nor Irv Pankey had been known for following the paths well travelled in late 1970s America.

Ms Sailor, one of the few female business administration majors at Penn State, had mustered the courage to accuse one of the school’s football players – a stranger to her – of raping her at knifepoint in her own home. Mr Pankey, who was just one of a dozen Black football players on the college’s juggernaut of a team, heard Ms Sailor’s evidence in court – and believed her.

It was 40 years before the MeToo movement and decades, too, before societal attitudes changed towards rape. But Mr Pankey became Ms Sailor’s protector and advocate in a heartwarming story borne from tragedy – and a new short film is finally shedding light on the unlikely bond forged between marginalised students on a polarised campus in a volatile time amidst horrifying allegations.

At the centre of it was the opposite of the marginalised: a tall, strong, self-titled “All-American” white player from Long Island named Todd Hodne. Nicknamed the Penn State Rapist, he ended up in prison for a series of assaults, killed a man while on parole and died behind bars in 2020.

But that’s not what interested Nicole Noren, who directed Betsy & Irv, in the case.

Her ESPN colleague, Paula Lavigne, had been working on an in-depth piece about Hodne, hearing details of Ms Sailor’s incredible friendship with Mr Pankey in the process. Speaking about it, the colleagues agreed “how rare it was – and we knew that there was something very unique that had happened here that we don’t see a lot,” Ms Noren tells The Independent.

They decided to make a short film about the incredible Penn State story; it premiered last month at the Santa Barbara International Film Festival and became available to stream this week on ESPN+.

“The feedback that has really surrpised me is coming from men, honestly, a lot,” Ms Noren says. “It really hadn’t occurred to me how many times there are other people out there doing this type of thing ... I think it’s really resonating with many, many people who have either been a Betsy or been an Irv.

“They understand, on a very intimate level, how Irv’s actions either did affect them or could have affected them or could have made their trauma a little more manageable.”

The director says that “many of these things that are now being taught to other students, to counsellors, to police, to different people, even trauma nurses ... they’re being taught these things that Irv did on his own.”

She adds: “He was just being a kind and good person.”

Mr Pankey shone as a role model as his fellow player, Hodne, brought shame upon the Penn State team, coached by the legendary – and locally nearly canonised –Joe Paterno.

Hodne, who grew up in Wantagh – a middle-class town on the picturesque South Shore of Long Island, home to a significant population of cops and firefighters – had already been in trouble with the law for stealing before he was recruited for the Penn State team. His fair hair and sharp jawline, however – and intimidating athletic prowess, especially when it came to tackling – seemed to help him sail through minor troubles.

In college, however, his antics were escalating – and a year after starting at Penn State, he was terrorising women on and near campus with a string of vicious assaults. One of his victims was Betsy Sailor, a 21-year-old living in a basement apartment off-campus; she’d placed a newspaper add for a roommate and had been fielding calls in response on 13 September 1978.

After shopping for groceries, she returned home and was “doing all the silly stuff you do when you’re all by yourself,” she says in the new Betsy & Irv. “I was singing loudly and dancing with the refrigerator door, and being very much myself.”

In the course of that, however, she realised she had a quiz the next morning and headed back into her bedroom to study.

“The light didn’t work,” she says. “The very next thing, I had a hand over my mouth and a knife in my neck and a person saying to me, ‘If you make a sound, I will kill you.’

“He put his hands around my arms and dragged me towards another bedroom, threw me down on the bed face-first,” she says in the film. “He is tying my hands behind my back; he also tied a scarf, blindfolded me. I remember asking him at one point, ‘What are you going to do?’

“He simply stated, very matter-of-factly: ‘I’m going to rape you’” – and proceeded to attack her for about two hours, she says.

“I made a calculated decision, on more than one occasion, that I was not going to try to escape,” she says in the film. “I was too afraid that he was going to kill me.”

When he finally stopped and she determined that he’d left, Ms Sailor – who’d been actively trying to commit the smallest details to memory about her assailant – freed herself of the restraints, called authorities and her mother, who lived a few hours away.

“I called my mother and ... I didn’t want to use the words, ‘rape,’” Ms Sailor says in Betsy & Irv, tearing up more than four decades later. “Because I thought, ‘That’s just too big of a word, too emotionally charged.’ And I ... [didn’t want] my mother to hear that.’”

About a month later, Hodne was arrested “on the strength of three fingerprints and a traced phone call” to another victim, write Ms Lavigne and Tom Junod in their bombshell ESPN piece, Untold.

“Five months later – two months after Penn State and Paterno lost the national championship game to Alabama and Bear Bryant – Hodne was found guilty of criminal sexual assault after one of his victims testified against him.”

That was Ms Sailor – whose testimony before the courts and the school not only got Hodne kicked out of Penn State but also destined for prison. (While inexplicably out on bail, before serving any significant time, Hodne went on to assault more women in his native New York.)

When Ms Sailor spoke out against Hodne in court, many of his football teammates were present. One truly heard her.

“She was bold enough to stand and get up there and speak on her behalf at a time where, on any college campus, women weren’t reporting rapes,” Mr Pankey says in Betsy & Irv. “Women were villified – ‘Look what she was wearing, look how she was acting, she shouldn’t have been at the party drinking.’

“When Betsy testified, I thought that took a hell of a lot of courage and self-fortitude to be able to do that.”

So he decided to throw his weight – physically and socially, as a revered Penn State player – behind the curly-haired student. He turned up at the door of her dorm room, since she’d moved on campus after the traumatic attack.

“He put out his hand ... [and said] ‘Hello, my name is Irv Pankey,’” Ms Sailor says in the documentary. “I just wanted to let you know that I was in the court, and I listened to what you had to say, and I believe every word that you’ve said. You will never have to be afraid or be alone again; I will be by your side.’”

The unlikely pair began palling around at Penn State; Mr Pankey says in the film: “Something bad had already happened to her that kind of set her apart. I just didn’t want her to feel that someone didn’t care.

“That was my main goal ... to try to let her know, ‘This ain’t a football thing.’ It was a Todd thing. And that she was okay with us.”

And there was clearly a ‘Todd thing:’ In advance of one of the player’s parole hearings years later, John B Collins, who prosecuted one of Hodne’s crimes, sent a letter to the parole board.

“I have been a prosecutor for nearly 30 years,” it read, according to Untold. “I have prosecuted serial killers and capital cases. Todd Hodne, to this day, remains among the three most dangerous, physically imposing and ruthless excuses for a human being I have ever faced in court.”

The extent of that ruthlessness wasn’t widely known yet, however, as Ms Sailor finished out her time at Penn State, where the football team was becoming more of a legend than a group of athletes. Mr Pankey’s unconditional and unprompted support was invaluable, she says.

“He gave me a bit of freedom that I wouldn’t have had otherwise,” she says in Betsy & Irv. “He would have the occasional get-together at his house, and I was invited; everybody knew who I was. I don’t know if Irv had a talking to them or whatever, but there was an understanding there.

“I felt a bit of respect, and the respect came from, I believe, a woman that was taking on something quite large. And the majority of people that I was dealing with were Black football players that had certainly been up against battling big things in their lives.”

After Penn State, Mr Pankey went on to play 12 seasons in the NFL; he and Ms Sailor, in the days before social media, lost touch. But they reunite in Betsy & Irv, where their mutual admiration and love nearly jump off the screen more thaon 40 years later.

Ms Noren, who has interviewed many survivors of sexual assault, tells The Independent: “We’ve seen where other people have kind of stepped in, whether they were friends or people in the athletic department or coaches, but we had never heard of someone so just blatantly kind of going forward, kind of by [a moral] code.

There’s often a “circling of the wagons that can occur” with sports culture, cometimes “male culture, ‘bro’ culture ... we saw it so many times where this didn’t happen. So for us, to hear when it happened with Betsy and Irv, it was just very surprising – and I think the most surprising part was just to see the effect of it and how it altered her life, in that it really just helped her be able to feel like she wasn’t an outsider or a pariah.”

![Nicole Noren, 46, directed Betsy & Irv, telling The Independent : “We had never heard of someone so just blatantly kind of going forward, kind of by [a moral] code” in support of a football player’s rape victim](https://static.the-independent.com/2022/04/21/18/Director%20nicole%20noren%20Mug%20Full.jpg)

Ms Noren hopes that anyone who sees the film will walk away with the realisation of “the long-term effect of this – and that’s what Paula [Lavigne] and I were very eager to share with people ... This is what can happen. It doesn’t have to be as bad.

“Every survivor obviously [is] very different with how they’re going to respond, especially to trauma, but people would be much more set up to be ableto survive and thrive again if they had people believe.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments