Italy remembers the judge who took on the mafia and paid with his life

Giovanni Falcone was killed in a bomb attack in 1992 but his work lives on, reports Sofia Barbarani in Rome

Italians on Monday marked the 30th anniversary of the killing of Giovanni Falcone, a pioneering Sicilian judge who was murdered by the mafia after dedicating his career to combatting the criminal organisation.

In a touching tribute in the Sicilian city of Palermo on Monday morning, Italian officials, including president Sergio Mattarella and foreign minister Luigi Di Maio, members of the police force and a crowd of supporters gathered to pay homage to the late judge.

“The firmness of his work was born from the deep-rooted belief that there was no alternative to complying with the law, at any cost, even of life,” President Mattarella said of Falcone.

The attack took place in 1992 on a highway near the town of Capaci, 20km from Palermo. Falcone, his wife Francesca Morvillo and three police escorts were killed when a bomb ripped through a stretch of motorway.

Falcone, driving a white Fiat Croma, was returning from Rome for the weekend.

The blast was so powerful that it registered on local earthquake monitors. Incredibly, some in the convoy survived.

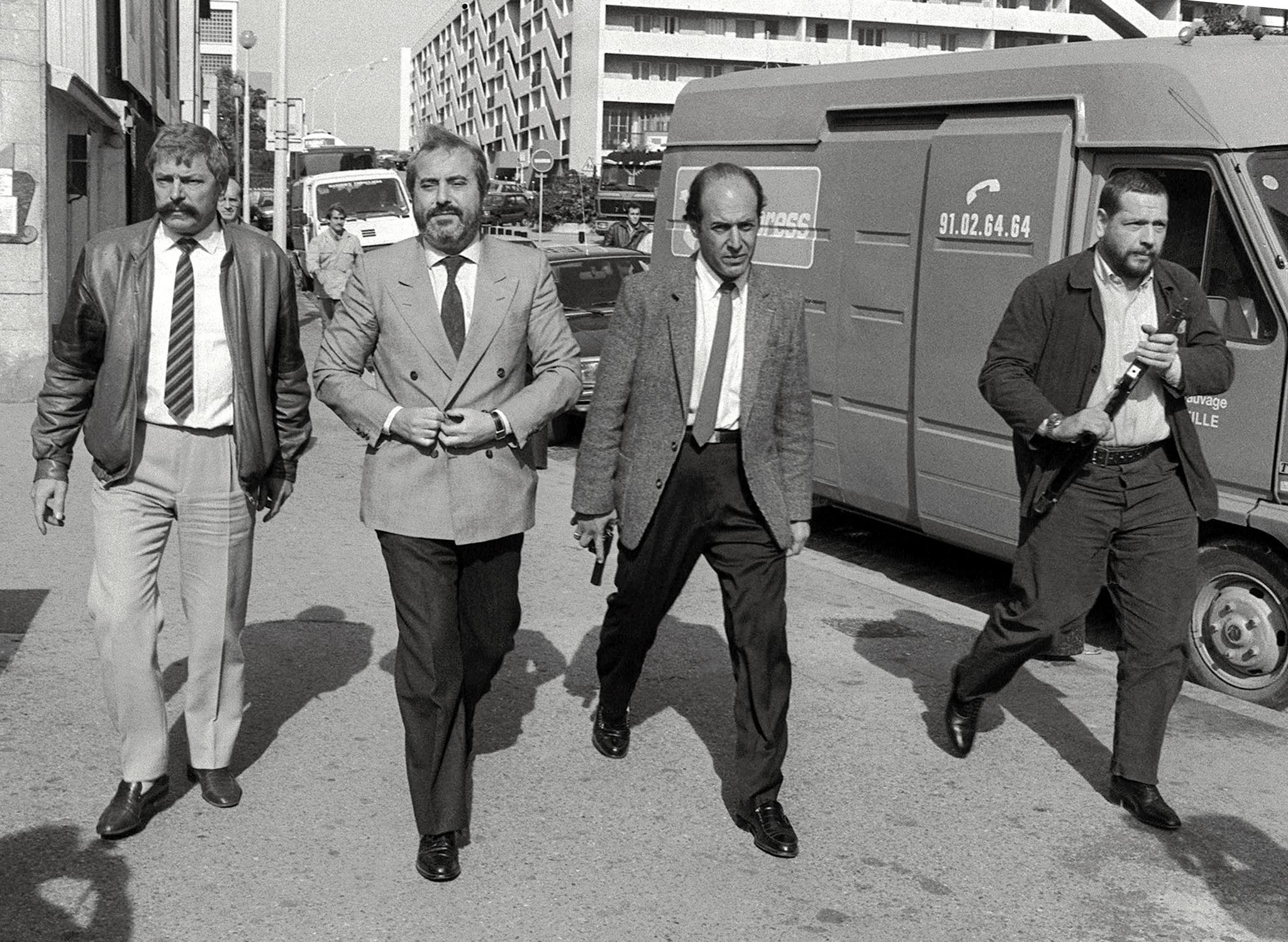

The attack was ordered by Salvatore Riina, the head of the Corleonesi mafia organisation, whose killing spree in the early 1990s also led to the death of Paolo Borsellino, another prominent anti-mafia judge.

Riina’s nickname was “the beast” and he was known for violently targeting rivals. One of his most loyal hitmen claimed he murdered up to 200 people on behalf of his boss.

The two judges led the Maxi Trial which resulted in the conviction of more than 300 mafia members. Riina was given a life sentence in absentia and was imprisoned after being found in Palermo in 1993. He remained in jail until his death in 2017, serving a large part of his sentence in solitary so he could not have any control over his organisation from behind bars.

In death, the authorities got some measure of revenge by denying him a public funeral.

Palermo International Airport was named Falcone-Borsellino Airport in honour of the two judges.

Italians often refer to the violent killing of Falcone as a turning point in how the country viewed the criminal organisation. Many were shocked by the level of violence and number of killings carried out by the mafia.

“The unprecedented violence provoked a reaction,” interior minister Luciana Lamorgese said at the memorial ceremony. “It was understood that the stakes were very high: it was a question of protecting the freedom of citizens.”

Falcone was also the first investigator to understand the importance of following money.

“As [Falcone] says ‘drugs may leave no trace, but money certainly does’. Thus, banks in Palermo suddenly find themselves inundated with court orders to reveal details of financial dealings,” tweeted Nick Withorn, a translation researcher specialising in Italian anti-mafia terminology.

Although Falcone’s work didn’t put an end to the mafia, it encouraged Italian citizens and institutions to speak out against them.

In a statement issued on Monday, the European Laura Codruța Kövesi praised Falcone for inspiring her with “ his professionalism, integrity and courage”.

“This day, however, is an occasion for all of us to realise what happens when criminal organisations are not fought with the utmost determination at all times: they grow,” said Kövesi in a statement.

“If we do not fight them efficiently, they not only poison local communities, they end up capturing the State. Their power is proportionate to the profits we let them accumulate over time. They distort the economy and corrupt our institutions only to the extent that we allow them to do so.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments