India’s coal problem under fresh spotlight after IPCC’s ‘now or never’ warning on climate

While the IPCC report warns coal needs to be shunned, across India, 281 coal plants are operating, 28 are being built and another 23 are in pre-construction phase, reports Stuti Mishra in Delhi

This week’s landmark United Nations climate assessment report has warned there is no space for new coal plants if the world wants to reduce the rate of climate change and usage will have to go down by 95 per cent in the next three decades.

The warning against using fossil fuels, particularly coal, isn’t new, but the issue remains to be a point of contention between developing and developed countries.

Reportedly, one of the reasons behind the delay in publishing the latest chapter of the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report – two assessments of which have already been published in recent months – was the insistence from some countries that their right to development should be recognised, and coal plays a crucial role in that.

India was among those pushing for recognition that developing countries have contributed a far smaller share of the carbon dioxide emissions already in the atmosphere than industrialised nations and therefore should not need to make the same steep reductions, the Associated Press reported.

The IPCC’s report focuses on mitigation, including technology development and transfer with the aim of holding warming to within 1.5C, or 2C, the target of the Paris agreement.

That would require using about 95 per cent less coal, 60 per cent less oil, and 45 per cent less gas by 2050, the report noted. It also called for ending the use of all unabated coal plants that are not equipped with carbon trapping technologies.

While it requires all countries to increase renewables and phase out fossils, it is far easier for developed countries that have more natural gas resources to transition than for emerging economies like India that rely majorly on coal for 70 per cent of their energy needs and have to choose between developmental goals like making electricity available to more people and climate action.

India’s dependency on coal is far bigger than just energy requirements, which can be switched to renewables over time. Some 3.6 million people are directly employed by the coal sector and there is also the economic dependency of cities, in the form of taxes, and other sectors it supports.

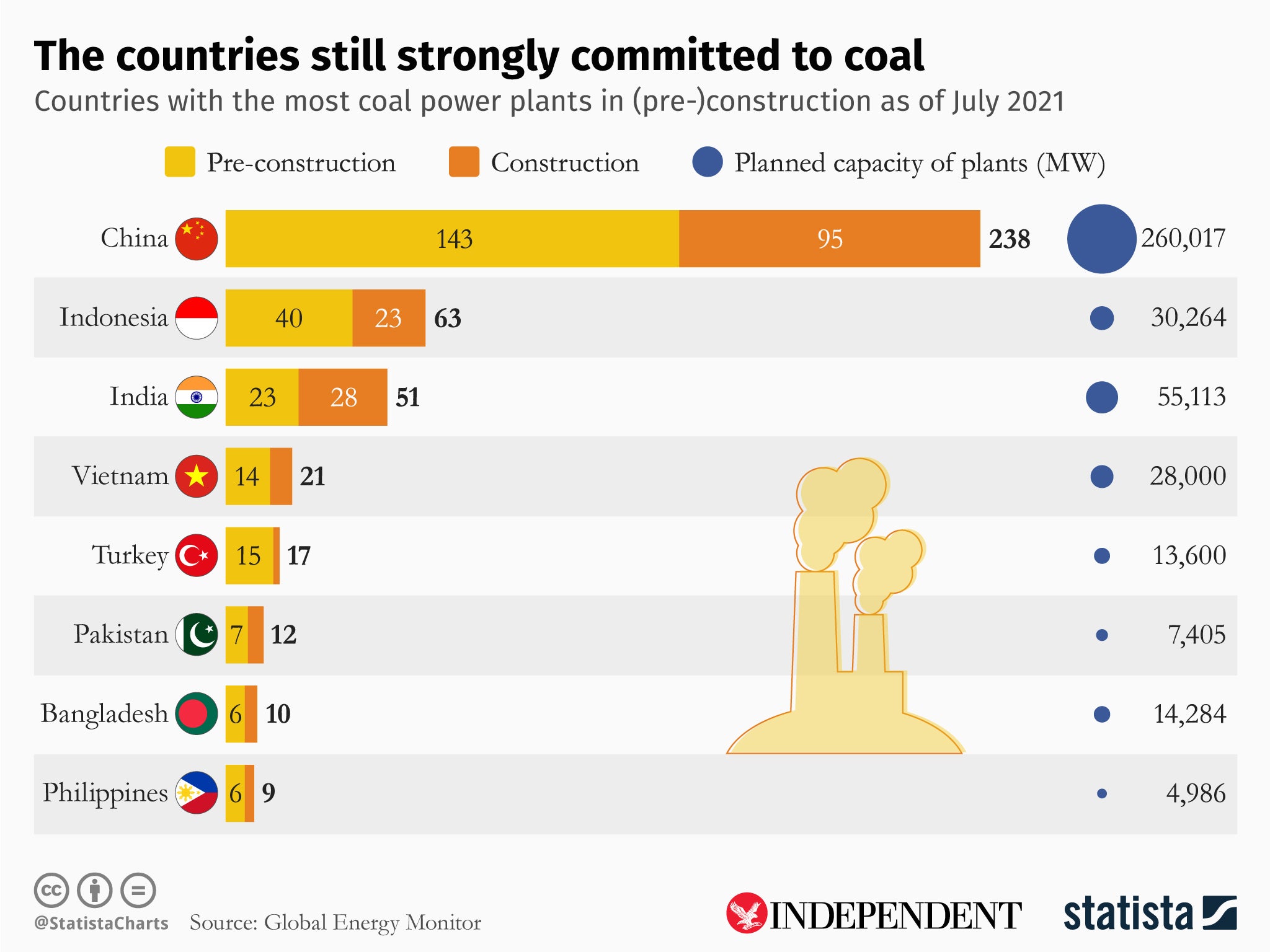

Across India, 281 coal plants are operating and beyond the 28 being built another 23 are in pre-construction phases, according to data from US nonprofit Global Energy Monitor (GEM). More than 90 per cent of the 195 coal plants being built around the world are in Asia with India, China and Indonesia, which remain highly dependent on coal, building the most.

While the IPCC report calls for only “unabated” coal power plants – those not mitigated with technologies to reduce emissions – to be shunned as a means for mitigation, the adoption of Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS), an expensive and water-intensive technology, in coal-fired power plants in India also remains poor.

There is no promise from the Indian government that the new plants that are under construction will be coming with the CCS in place. However, India does have ambitious goals of building renewable energy capacity.

In August this year, the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy declared it has installed 100GW of renewable energy capacity with an additional 50GW being installed and 27GW in the tendering process. India’s prime minister Narendra Modi announced as an extension to its previous Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) that the country will target 50 per cent of the installed capacity of renewable sources by 2030.

This came on the sidelines of the Cop26 summit when the country announced its net-zero target of 2070. However, the summit was also mired in the similar discussions that reportedly caused the delay in the publication of the third assessment report of IPCC.

India had raised objections to the language of “phasing out” coal in of final agreement at Cop26 summit, which was looked at as an attempt to water down the agreement. However, Indian officials at the summit told The Independent that the difference in treatment “between coal and other fossil fuels” was something that India objected to.

The country either wanted the language to read that all fossil fuels should be phased out and historical responsibility of carbon emissions, largely borne by nations that began industrialisation earlier than others, to be taken into account.

New Delhi has time and again said that India’s historical emissions and per capita emissions are minuscule in comparison to the developed world, and it wants to exercise its right to development and to bring its population out of poverty.

The IPCC report, however, once again makes a similar distinction. It circles out coal as the most dangerous fossil fuel while it largely remains a cheap energy source for developing countries like India.

India imports 80 per cent of its oil requirements since it does not have enough of its own. How crucial it is for India can be seen from the fact that the country has not only continued to buy Russian oil but increased its imports due to a discounted rate despite international outrage citing its own energy security as the first priority.

Reuters has reported that India has already bought at least 13 million barrels in the weeks since Russia invaded Ukraine compared with some 16 million barrels for the whole of last year.

While matters of climate finance remain a conflict in international negotiations, including India’s demand for $1 trillion from rich countries to hand over to help poor nations, the latest report pays far more explicit attention to equity and justice – internationally and domestically – than previous IPCC reports.

“While there is evidence that international agreements like the 2015 Paris Agreement are working to enhance national target setting, policy development and transparency of action and support, there are significant shortfalls in the availability of support which will make it increasingly challenging for developing countries to implement current commitments and take on more ambitious national contributions over time,” Professor Lavanya Rajamani, one of the authors of the report said,

“Financial flows are a factor of three to six below what is required by 2030 to limit warming to 1.5C or 2C, and closing this gap is particularly hard for developing countries,” Navroz Dubash, one of the authors of the report and professor at the think tank Centre for Policy Research, said.

However, he added: “The report recognises that equity remains a central element in UN climate negotiations, despite shifts in understanding of differentiated responsibilities of countries over time and challenges in assessing what is a fair contribution of different countries.”

However, the IPCC report also suggests a broadening in how we look at the relationship between development and climate action. It calls for cities to improve energy efficiency through better building strategies to reduce urban emissions. This could be the key climate action for developing countries like India. Experts say the developmental policies of emerging economies need to be drafted keeping the climate crisis in mind.

“Development actions are also climate decisions and vice versa,” Mr Dubash said. “Climate and development can no longer be seen as separate issues – development decisions are climate decisions, and vice-versa.”

One optimistic update for India and other developing nations from the report is the lowering cost of renewables.

The report said such costs – solar and wind energy, plus batteries designed to store the energy they generate – have gone way down, making them more competitive with gas and coal, and in some cases, cheaper.

Since 2010, they have shown “sustained decreases of up to 85 per cent,” according to the report. More affordable renewables should help lower the cost barriers associated with transitioning away from fossil fuels and accelerate the transition for countries like India.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks