‘Crimes must go to court’: France confronts its grisly Algerian war past

The Paris government’s decision to release archives on the war of independence have prompted fresh calls for justice, reports Peter Allen

Mohammed Endarek was a teenager when he witnessed a series of murderous attacks carried out by Paris police officers.

He watched helplessly as scores of Algerians, including close friends, were beaten repeatedly with truncheons and rifle butts before being thrown into the River Seine.

As many as 300 mainly young men were killed on a single night in 1961 as they called for France to abandon the Algerian war of independence – arguably the most savage conflict in the history of decolonisation.

Now, more than six decades on, survivors such as Mr Endarek may finally be able to view top-secret documents about the atrocity.

It follows a French government announcement that a 75-year-rule preventing the release of national archive files on the 1954-1962 Algerian war is being reduced by 15 years.

“Nobody was ever brought to justice for the slaughter in Paris, despite hundreds of police being pictured as people were murdered all around them,” Mr Endarek, who is now 79, told The Independent.

“It was the same throughout the war – the French army and police killed, tortured and imprisoned with impunity, with nobody once bothering to release records about what was going on, let alone investigating the crimes.

“We all want to read those names, and to find out what they had to say for themselves. Many of the killers were not much older than me.”

Mr Endarek became caught up in fighting on the Saint-Michel bridge, the popular tourist spot opposite Notre Dame Cathedral, on 17 October 1961, when he was 19.

“There were armed police everywhere, and they were specifically looking for anyone who had dark skin. Pretty much everyone risked a beating, but I managed to get away. Many were pulverised, despite being unarmed and protesting peacefully.”

Arezki Amazouz is another veteran supporter of the Algerian nationalist struggle who has been calling for greater transparency for decades.

“We have a good idea about the death toll and the wounded, but there is so much left to learn,” said Mr Amazouz.

“That’s why we have organised petitions calling for the opening up for of archives that have been closed for far too long.

“More investigation is needed and, if possible, those ultimately responsible for the crimes should be judged in court. There is ample evidence for convictions.”

Algeria – now the largest country in Africa by land mass – was considered part of the French mainland during 132 years of occupation from 1830.

The colonisers were defeated in 1962 by the Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN – Front de Libération National), and since then the French have largely managed to draw a shroud over this dark period of history.

It was only in October this year that President Emmanuel Macron finally attended a low-key commemoration to those murdered in 1961, and even then, there was no public apology.

“This needs to change, and it needs to change soon,” said Ahmed Touil, who was just 13 when he was caught up in the anti-war protests in Paris.

There were armed police everywhere, and they were specifically looking for anyone who had dark skin

An iconic photograph that appeared on the front page of France Soir in October 1961 portrays the young Ahmed as one of hundreds of children separated from their parents, and brutalised by the police.

Like many, Mr Touil now likens the opening of the Algeria files to the process by which the French finally owned up to collaborating in the Nazi Holocaust during the Second World War.

It was in 1995, half a decade after some 75,000 Jews were rounded up by the French authorities and sent to the gas chambers, that then-president Jacques Chirac finally confessed.

Blaming the horror on “the folly of the French state”, Mr Chirac said: “Breaking its word, France handed those who were under its protection over to their executioners.”

The Paris police commander ultimately responsible for the 17 October massacre was Maurice Papon, who was also a notorious Nazi collaborator.

He was finally convicted for crimes against humanity in 1998, but this was in relation to his conduct during the Holocaust, and not against Algerians.

Campaigners now point to up to 1.5 million Algerian civilians perishing in the 1954-62 war alone, with many more being wounded.

As throughout the history of France’s colonial adventure in Algeria, entire villages and towns were targeted, and the latest military technology used to wipe out communities.

Gas chambers, Napalm and illegal executions were all deployed by the French military in support of their European settler allies, who were known as pieds-noirs – or black feet.

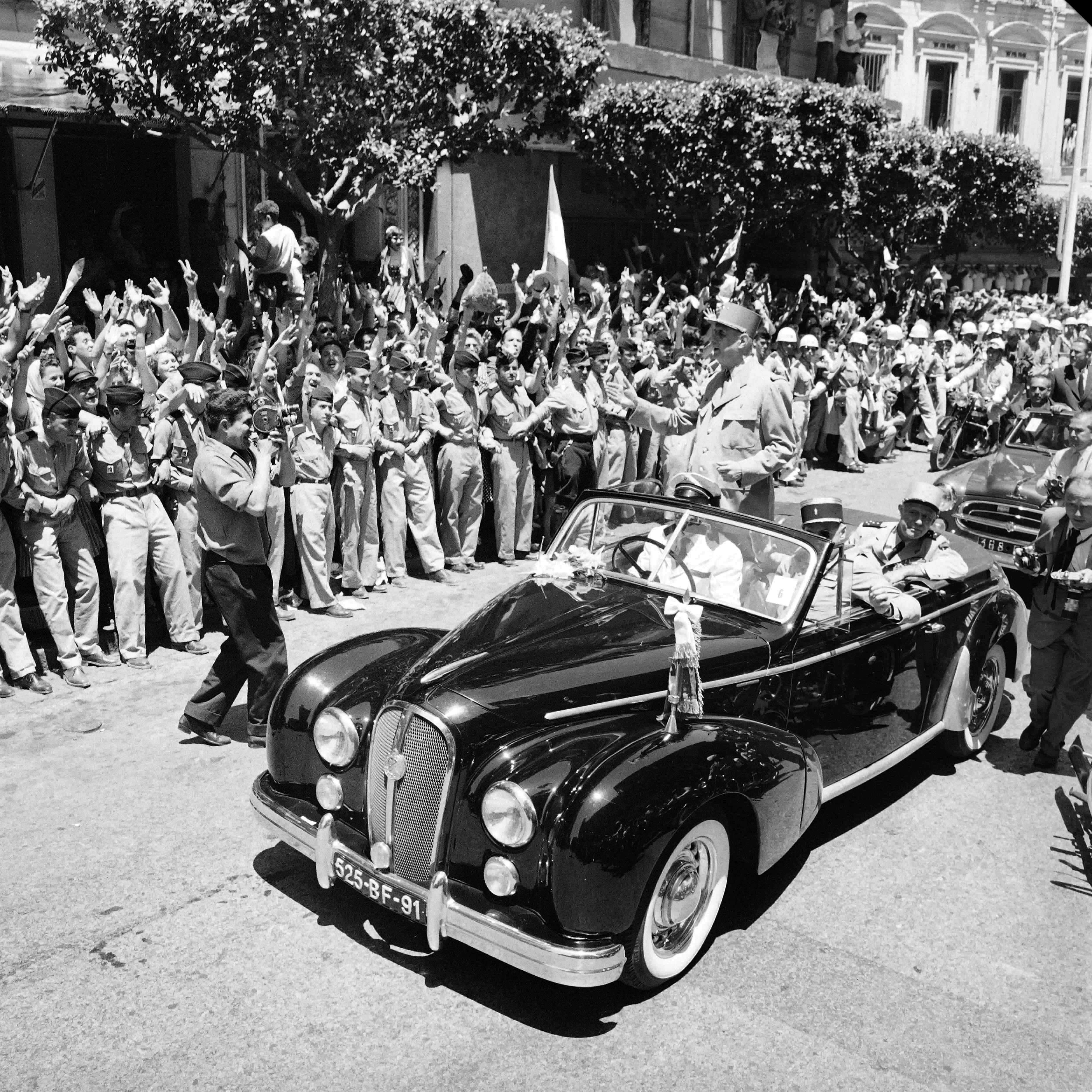

The militant French were supported by their own terrorists – the OAS, or Secret Army Organisation, which carried out numerous atrocities including trying to assassinate President Charles de Gaulle.

On 18 June 1961, 28 civilians were killed and 100 injured when an OAS bomb derailed a high-speed train travelling from Strasbourg to Paris – another crime that has never been investigated properly.

A French government spokesman described the release of the files as a chance for the country to “look the historical truth in the face”.

Just as the descendants of Nazi collaborators have done all they can to cover up collusion, so it is the same with French families associated with Algeria.

Relations between the Arab Muslim-majority country and its former imperial overlords are certainly permanently strained.

While welcoming the opening of the files, politicians in Algiers including President Abdelmadjid Tebboune, nevertheless remain uneasy.

Like Mohammed Endarek, they fear that the newly released information could well lead to an even sharper deterioration in the relationship between the two countries.

“When the truth reveals extreme evil, then those responsible prefer to keep it secret,” said Mr Endarek. “This is why disclosure is so important.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks