‘Hong Kong’s fight for freedom is ours as well’: Lord Patten hits out at Chinese leadership

Interview: As his diary from his time as Britain’s last governor in Hong Kong is published, Lord Patten tells Rory Sullivan its democracy movement is seen as an ‘existential threat’ by Beijing

A quarter of a century ago, the sun finally set on one of the British empire’s last holdouts. With pomp and ceremony, the UK returned Hong Kong, an imperial possession it had held for more than 150 years, to China.

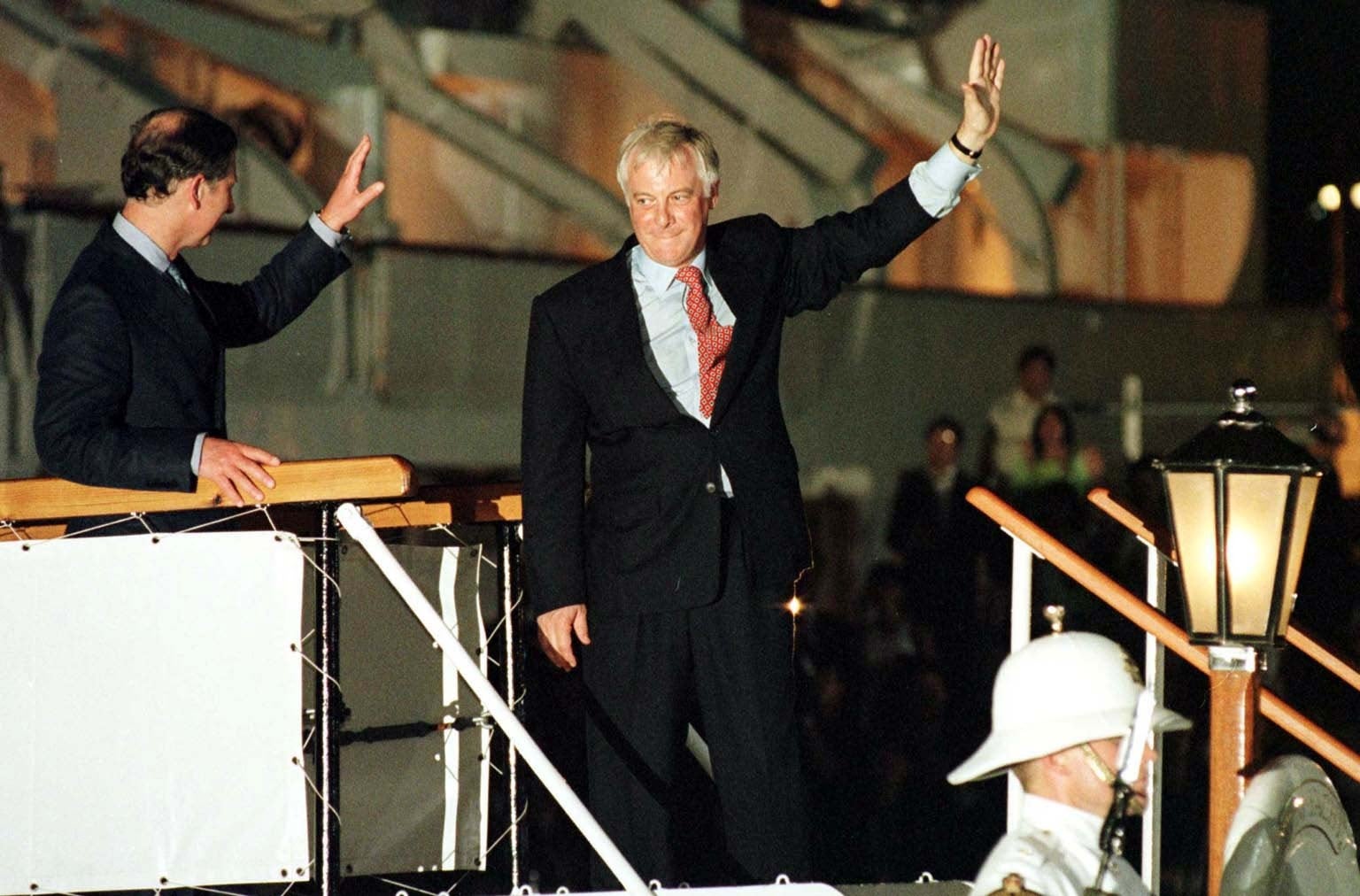

The colonial administration bid its final farewell as Chris Patten, a former Tory minister who had served as Hong Kong’s last British governor, boarded the HMS Britannia on 30 June 1997.

“It was a wonderful city. Like a lot of the great port cities, very extrovert and spectacularly successful,” he says, reflecting on the place that was his home for five years. “I hugely admire the people of Hong Kong, who are incredibly gutsy and generous,” he adds.

Lord Patten’s nostalgic description of Hong Kong, along with his homage to its people’s stoicism, is telling: it is now a markedly different place from when he left, especially following Beijing’s brutal crackdown on individual freedoms after a wave of mass demonstrations in 2019.

The most ominous erosion of liberty seen in Hong Kong was Beijing’s introduction of a national security law in the summer of 2020. Under its broad remit, pro-democracy activists have been jailed on charges including sedition and subversion. Thousands of Hongkongers have decided to flee their homeland as a result of the worsening political climate.

Against this oppressive backdrop, Patten characterises his mood as one of “awful sadness”.

“Without going into details, some of the people who have been locked up are friends of mine. The Chinese have gone about it with a vengeful comprehensiveness,” he says, noting Beijing’s broken promise to adhere to the policy of “one country, two systems” until 2047.

The British peer says it is hard to overstate the importance of the territory’s struggle against authoritarianism. “Hong Kong’s fight for freedom, for individual liberty and decency, is our fight as well,” he writes in the conclusion of The Hong Kong Diaries, his contemporaneous account of his governorship.

But democracy and Hong Kong did not always go together so closely. After visiting Hong Kong for the first time as a young backbench MP in 1979, Patten wrote an article in the British press calling for direct elections in Hong Kong’s local government, a proposal that he admits proved “very unpopular” with the then governor.

A few years later, Teddy Youde, Hong Kong’s next leader, “certainly tried to speed up the steady development of democracy” but was opposed, Patten says.

When Patten assumed the job in July 1992, after losing his West Country seat in the British general election, Hong Kong had a partly elected legislature. But by his own admission, it was still some way off being a fully fledged democracy. “The people of Bath elected the leader of Hong Kong,” he says of his own appointment.

However, in the eyes of the former Conservative Party chair, things were changing fast in Hong Kong, spurred on by fears that arose following the Chinese government’s massacre of students in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square in 1989.

“There was this network of freedoms in Hong Kong, and people wanted more of them. They wanted more democracy,” Patten tells The Independent over coffee in his west London house.

“And what we had to do, certainly from 1992 to 1997, and not least in the wake of people’s nervousness about Tiananmen, was to involve people in Hong Kong in deciding how much more we could do without bringing the house down.”

His administration faced the challenge of being criticised both by China and by some members of the Foreign Office and Britain’s business community, who deemed it unwise to provoke Beijing in the lead-up to the handover.

Sir Percy Cradock, a leading Sinologist who had helped to draw up the Joint Declaration – the agreement underpinning Britain’s withdrawal from Hong Kong after its lease expired in the summer of 1997 – was one of Patten’s strongest critics in Britain.

Doubters like Cradock were “blind” to the change in atmosphere after 1989, Patten argues. “There’s no way, after Tiananmen, that we could have said to people, ‘We’re not going to take any notice of your concerns.’”

Patten, who is now the chancellor of Oxford University, also dismisses those who thought the UK should have prioritised its economic relationship with China over political issues in Hong Kong. For him, it was wrong to treat Hong Kong as a “pebble in the sandal” of the relationship, given it was one of the world’s largest trading communities, and it was mistaken to think that British business interests in mainland China would be adversely affected by the diplomatic wrangling.

To reinforce his point, the 78-year-old describes Hong Kong’s democratic changes in the mid-1990s as “very mild”. He explains that while the voting age was lowered to 18, and while more people could vote in constituencies determined by their profession, there was no increase in the number of directly elected seats. “None of it was exactly radical,” he says.

“I always thought it was more than slightly flattering for Chinese propaganda to make me out as a sort of latter-day Thomas Paine,” he adds.

Some people still feel differently about Britain’s approach to Hong Kong in the last years of its rule. One UK businessman, who moved to the territory in the late 1980s, says the desire to inject more democracy into its political apparatus after decades of colonialism was “a strange reading of the situation”.

Speaking anonymously, he believes the UK should have done less to antagonise Beijing, saying Britain had placed a tinderbox beneath Hong Kong rather than focusing on its continued prosperity.

“For a generation, Patten got away with it,” the businessman says of the democratic changes, arguing that they had a role in how things have subsequently played out.

In response to this sort of criticism, Patten thinks it is “insulting” to suggest that Hongkongers, many of whom were political refugees from mainland China, were only interested in money and not politics. He also suggests that British policies have had nothing to do with the recent upheaval in Hong Kong, which he blames squarely on China’s current leadership.

“I do think that, before Xi Jinping, things weren’t going so badly. Hong Kong was still identifiably Hong Kong. The situation undoubtedly changed with Xi,” he says.

The Chinese leader, who became president in 2013, started to target freedom of speech and other liberal democratic values, Patten says. It was no surprise that he and his acolytes’ attention soon became fixed on the former British colony, he notes. “I think Hong Kong represents for Xi an embodiment of that existential threat.”

In a world in which illiberal countries such as China and Russia threaten global stability, Patten wants to see liberal democracies “stand together in a way that, on the whole, we have not done”.

As an example, he mentions China’s decision to impose import bans on some Australian goods, after Canberra asked the World Health Organisation to investigate Beijing’s alleged cover-up of the first Covid-19 outbreak.

“When something like that happens to another democracy, we should all stand beside them,” Patten says. “I’m not in favour of a new cold war, or of containing China. But I am in favour of constraining China when they behave badly.”

Patten points out that the backsliding of democracy in the US could prove a pitfall in the search for a joined-up approach against China.

“We won’t do what is required unless America is working with Europe. And unless America does really demonstrate that it believes in democracy, then we’re going to have a hell of a time. It’s not obvious to me at the moment that the leadership of the Republican Party does believe in democracy.”

Another potential handicap is Britain’s continued clashes with the EU over post-Brexit arrangements, he says.

Overall though, Patten is of the opinion that Britain’s position on Beijing is getting better. “I think, until recently, the [UK] government has been a bit Janus-like on China. They’ve recovered from the so-called ‘golden age’ of China relations under Cameron and Osborne, which was a period of a massive and humiliating self-delusion.”

The discussion turns once more to Hong Kong, and then to a wider reflection on the world’s ill health.

“I live now in a state of constant depression and anxiety about it. I was editing my diaries at the same time as I was reading emails from friends and seeing how the concept of Hong Kong citizenship was being shredded... it hasn’t exactly been a happy experience,” Patten says.

Britain’s last colonial governor then changes the subject to Stefan Zweig’s The World of Yesterday, a “despairing book about night falling on Europe”. The day after sending it to his publisher, Zweig and his wife took their own lives, pained by the evils plaguing their continent.

Patten says Zweig would have been amazed by the progress made in the 1950s and 60s after the defeat of fascism. A similar bettering of the world is possible once more, he adds.

“It could all go right again. Will that happen? Who knows. I won’t live to see it.”

‘The Hong Kong Diaries’ by Chris Patten is published by Allen Lane on 21 June

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

15Comments