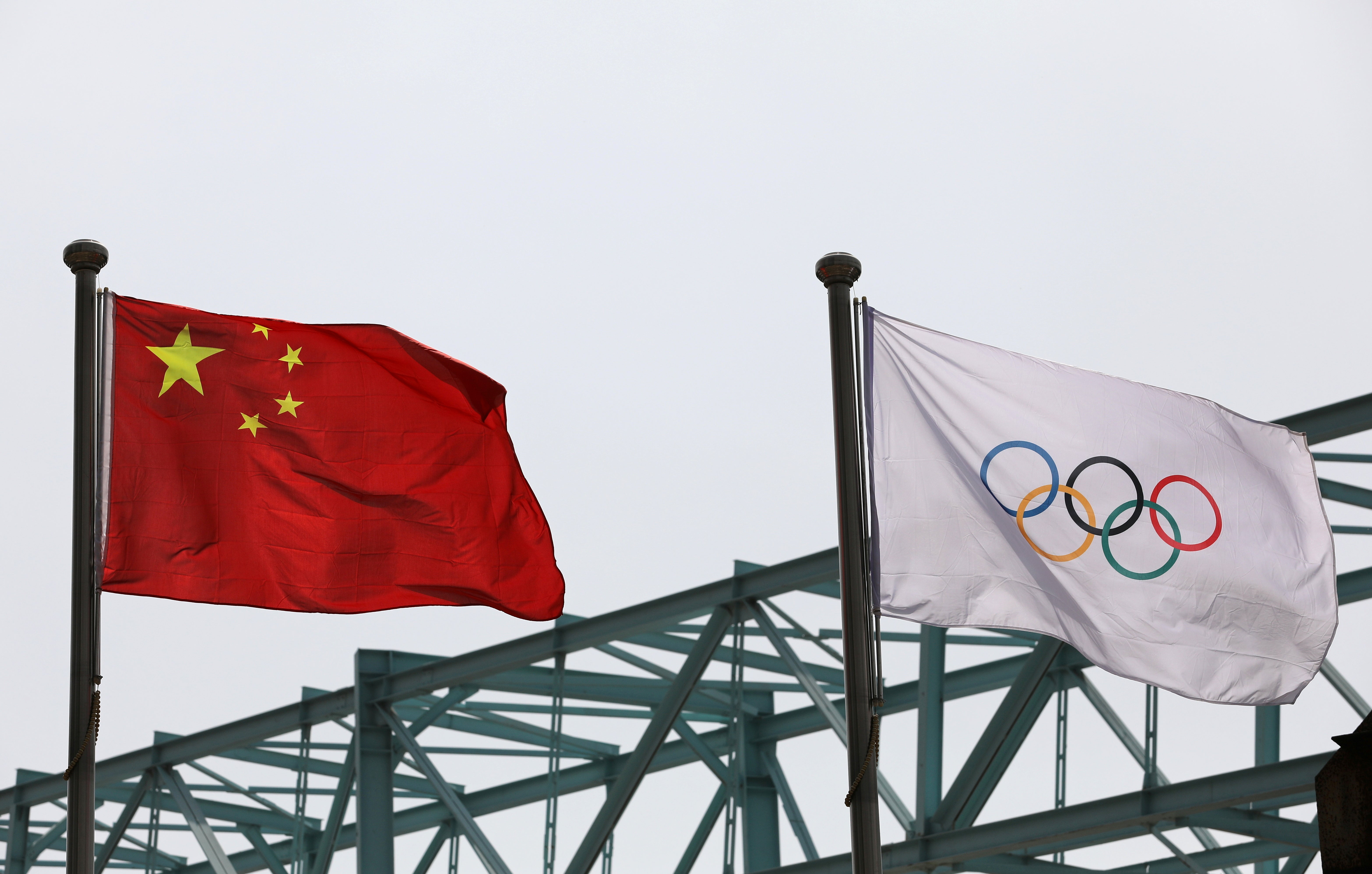

Beijing Olympics: Will countries announce a boycott of the 2022 winter games?

There have been growing calls to boycott the 2022 Olympics or move it from Beijing because of China’s human rights record, reports Akshita Jain

Even as uncertainty remains about the delayed Tokyo Olympics, the 2022 winter games set in Beijing have already started grabbing attention because of China’s human rights record.

There has been increasing pressure on countries and sponsors to not participate in the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympic Games and this month it seemed that the United States also put its weight behind boycott calls. A US State Department spokesperson said that it was “one of the issues that is on the agenda”, although a senior official later said that a boycott has not yet been discussed.

No country has yet officially announced a boycott, nor is it clear that any will, but the US official’s statement spurred a debate on how to approach China and the 2022 games which open on 4 February next year. Human rights groups have called either for a boycott or demanded that the International Olympic Committee (IOC) move the event out of Beijing.

Lawmakers in Canada and the US have also supported these calls. Canada’s House of Commons passed a motion calling on the IOC to move the games from China. A group of US Republican senators in February introduced a resolution with a similar call to change the location of the 2022 Olympics.

However, experts told The Independent that right now it seems unlikely countries will choose to not send their athletes to the games. They may use other forms of boycott – economic and diplomatic – or use the games to make a statement critical of China, they said.

“In general, decision makers tend to look back on the boycott of the 1980 Moscow Olympics as a failure, something that only harmed the athletes, and want no part of telling athletes not to compete,” said Ethan Scheiner, professor in the department of political science at University of California, Davis. He also pointed out that there is real fear of retaliation by China.

The US State Department statement drew an almost immediate reaction from China, with the government warning Washington not to boycott the games next year. “Politicisation of sports runs counter to the spirit of the Olympic Charter and harms the interests of all athletes as well as the international Olympic cause,” said foreign ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian. “The international community, including the US Olympic and Paralympic Committee, will not buy it.”

The spokesperson also rejected accusations of human rights abuses in Xinjiang, calling it the “most outrageous lie of the century”.

Professor Scheiner said that other types of boycotts are much more likely, referring to senator Mitt Romney’s idea of an “economic and diplomatic boycott” whereby foreign spectators and diplomatic delegations don’t attend the games.

In an opinion piece forThe New York Times, Mr Romney suggested that American spectators should stay at home and not contribute to the revenues the Chinese Communist Party will raise from hotels, meals and tickets. He also said that the president should invite Chinese dissidents, religious leaders and ethnic minorities to represent the US.

The condemnation of China and the opposition to the games being held in Beijing stem from China’s treatment of Uighur Muslims. The US accused China in January of committing “genocide” in its repression of the Uighurs and also declared it in an annual human rights report last month.

The US, UK and Canada in a joint statement last month expressed concerns over “China’s human rights violations and abuses” in the region. Beijing has vehemently denied all accusations, calling them “ridiculously absurd”.

China has also been criticised for its recent overhaul of Hong Kong’s electoral system and cracking down on dissent. It has also stepped up its military activities near Taiwan and aggression in the South China Sea.

Rob Ruck, professor in the history department at the University of Pittsburgh, said it’s more likely some athletes and nations will use the Olympic Games to make a statement that is critical of China. He said that would constitute a “symbolic rebuke” of China, which possibly views the games as they did the 2008 summer games to make a statement about their magnificence to the world.

Similar boycott calls have also been made about the 2022 Fifa World Cup which is being hosted by Qatar. A Guardian report said about 6,500 migrant workers have died in Qatar since it won the right to host the tournament back in 2010. Since the report came out in February, Doha has faced criticism by activists and protests by footballers during qualifying matches.

While no country has yet announced plans to boycott, Professor Ruck said that the Norwegian Football Association will vote in June on the boycott. He said that the association will be forced to abide by the result of the vote “because sport is organised in Norway on the basis of clubs to which fans belong as dues-paying members with one person getting one vote”. If Norway does vote not to take part in the World Cup, other nations might follow, he said.

The last major boycott of the Olympics happened in 1980 when the Moscow games saw many countries refuse to take part – including the US and Canada – in protest at the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, at a time of heightened Cold War tensions.

This time, amid mounting calls to boycott, persistent questions have been raised over how effective such a move will be in changing China’s policies.

“Boycotting the host country specifically for the actions that the government has taken has not previously resulted in a change in that state’s actions,” said Dr Heather L Dichter, associate professor of sport management and sport history at De Montfort University.

She said that the people who were hurt the most from the boycott of the 1980 Moscow Olympics were the athletes. An estimated 460 US athletes qualified for the 1980 summer games, but Olympics historian Bill Mallon said about half never competed in any games, according to The Wall Street Journal.

Activists have approached the Switzerland-based IOC to move the 2022 games out of China, but president Thomas Bach said the committee must stay out of politics. After failing to make progress with the IOC, they reached out to national Olympic committees, athletes and sponsors.

Airbnb has been asked by a coalition of 150 human rights campaigners to drop its sponsorship connections to the Beijing games. It is one of the IOC’s leading sponsors, alongside Coca-Cola, Samsung, Visa and Toyota. A letter sent by the activists said that Airbnb is trying to drive tourism in China “at the expense of Uighurs and Tibetans who cannot travel freely in the country”, according to The Associated Press.

Professor Dichter said that a boycott by sponsors would be even more difficult to arrange. Sponsorship deals with the IOC cover a four-year period, ending with the summer games (in this case Paris 2024), and those companies have to pay that money to the committee regardless or they would likely be in a breach of contract, she said. They have planned for activities at that event for years in advance.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks