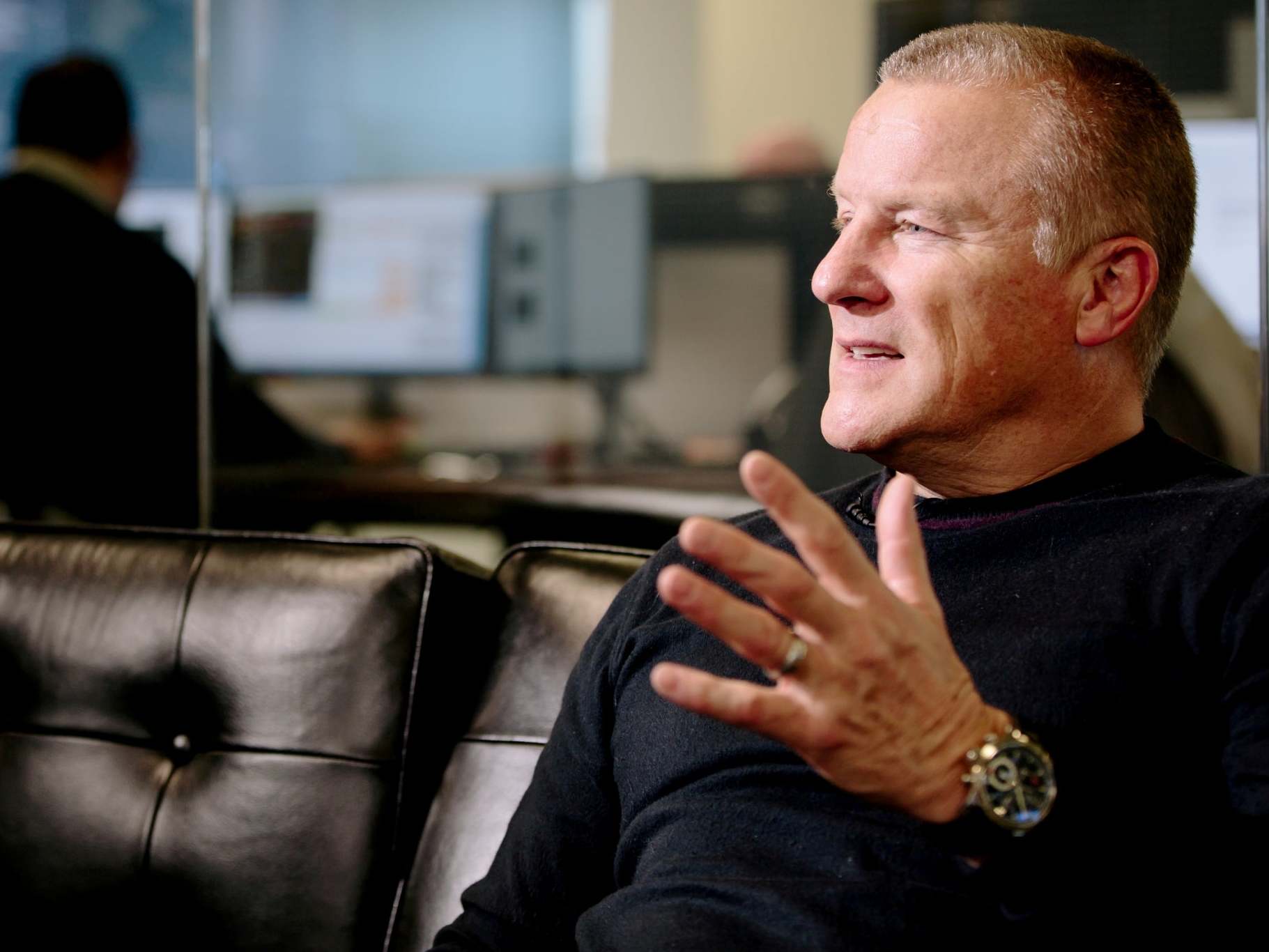

How the twin villains of hubris and ego brought down an empire

As far as the City was concerned, it was other people’s money – so chances were taken. Chris Blackhurst contemplates the fall of Neil Woodford and Lansdown’s part in the collapse of his funds

As the dust settles on the Neil Woodford investment empire, the overwhelming feelings are of anger and deja vu. We’ve been here before, through numerous scandals, and always the result is the same: the man at the top has seen his reputation trashed but has made tons over the years and that money, presumably, is safe; meanwhile, the ordinary punter loses their savings. And, yet again, between them is a respectable City brand that sold themselves on trust, and that reassurance was found to be wanting. Not for the first time, too, there is a regulator that failed to read the warning signs and did not act.

That thunderous noise you can hear is also one that is all too familiar to followers of these sad sagas. It’s of horses bolting and stable doors closing.

Now, of course, everyone is alive to what went wrong with the UK’s best-known fund manager and his stock-picking. They know that almost 300,000 customers of Hargreaves Lansdown saw their cash disappear as they followed the recommendation of the online investment management supermarket that made Woodford’s fund one of its “best buys”.

At the heart of this disaster is rank complacency and carelessness, driven by those three letters long-favoured in the City, and the cause of many a crisis: OPM or Other People’s Money. Those twin villains of ego and hubris played their usual crucial part.

When he was with Invesco, Woodford earned his stellar status on the back of buying stock in dull, unheralded companies that paid good dividends. So brilliant was he that Woodford attracted camp followers – he was watched like a hawk to see where he was going next, and others would quickly pile in.

Once he was on his own, impatient and possibly anxious to show he could repeat the trick, Woodford went for riskier tech and early-stage growth businesses. Unfortunately, too late, his supporters only noticed the shift when those purchases began to under-perform. Woodford could find no buyers for tech shares that were going nowhere except down. He and his fans were soon trapped in a vicious, downward spiral.

But where did those investors emanate from? There’s no doubt that they were drawn to Woodford by Hargreaves Lansdown. They were the same as would-be diners scanning a restaurant guide for somewhere decent to eat – they were entitled to reason that the compilers of the ranking had sampled the food, and were keeping it monitored. That’s why you pay good money for the guide; that’s why they paid a fee to Hargreaves Lansdown. No matter that Woodford gave Hargreaves Lansdown customers a discount for choosing his funds. The fact that Hargreaves Lansdown was promoting them, and putting them in its “Wealth 50” list, was the real attraction – the fee reduction was merely icing.

They still paid cash to Hargreaves Lansdown, even at the discounted rate, and it’s fair now, to ask: for what? They justifiably most likely thought at the very least the firm would have done due diligence, and Woodford’s funds were being highlighted for a reason.

What might have given them pause is if they were aware that Woodford’s inclusion on the list did not technically count as investment advice from Hargreaves Lansdown. Neither did the “best buy” rating fall under the aegis of the Financial Conduct Authority. As such, because it did not qualify as financial advice, it remained unregulated. No one was casting an experienced, objective eye over the “Wealth 50”, no one was asking why a fund was there, and whether it should remain.

Of course, when the Hargreaves Lansdown chiefs and the officials from the watchdog come to investing their own money they may take a different, more scrutinising attitude. But this was OPM, and the standards were not so high.

It was really all about marketing, about attracting investors and their cash, rather than paying due care and attention to where their money was heading. The more people who were drawn in, the greater the revenue for Hargreaves Lansdown, and the larger the fund for Woodford. Theirs was also a spiral for a while, one that was upward.

But shares can go down as well as up. It’s the most overlooked warning there is, the one that is usually gabbled at ferocious pace at the end of a radio promotion or is tucked away in the small print in a brochure or newspaper advertisement. People are not stupid – they know shares can fall. They know, though, that the investment platform is charging them, and they assume that someone they trust, someone they’re paying, is reasonably confident that these shares or in Woodford’s case, this fund, is not so risky.

It’s rank indifference, hypocrisy even, that never fails to deliver: on the one hand, a big City name is pushing something; on the other, the big City name has done virtually nothing to justify its branding being used. Without actually seeing it, you can imagine the shrug: it’s OPM, so who cares?

In the Woodford collapse, it would pay to see the internal workings of Hargreaves Lansdown in relation to him and his funds, and the correspondence between them. It’s possible that what might be revealed is a high degree of probing and questioning. Or not. I know which one my money is on – and I suspect it’s a safer bet than following Hargreaves Lansdown’s choice of Woodford.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments