Walking shark which ‘breaks all rules of survival’ studied by scientists for first time

Comparing how epaulette sharks move as they age could offer clues as to how they cope with challenging environmental conditions, reports Tom Batchelor

A newly discovered walking shark which scientists say breaks “all of the rules for survival” is the subject of a first-of-its-kind study by US and Australian researchers.

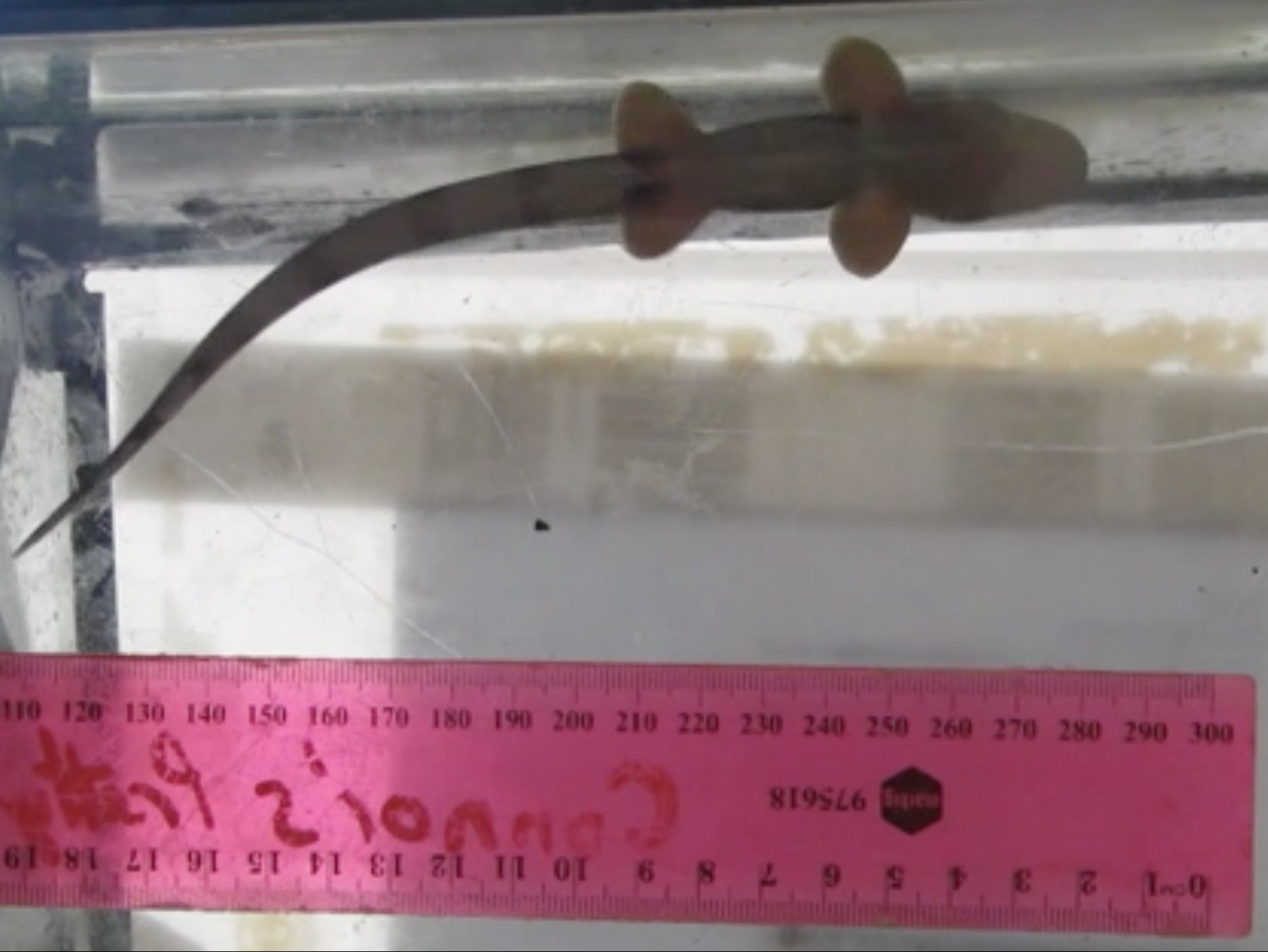

The epaulette shark (hemiscyllium ocellatum), found in the southern Great Barrier Reef, measures just 3 feet long and can walk both in and out of water by wriggling its body and pushing itself forward using its paddle-shaped fins.

Experts at Florida Atlantic University and James Cook University and Macquaire University in Australia examined how the shark’s walking and swimming changes during its early development – offering clues as to how these sea creatures may be coping with the impact of climate change.

Scientists believe the epaulette sharks’ ability to wriggle in and out of water may be key to its robust response to challenging environmental conditions, but until now no study has been undertaken into how they move during the first stages of their life.

Specifically, the researchers looked at the differences in walking and swimming in newly-hatched and juvenile sharks.

The youngest group retain an internalised yolk sac, resulting in a bulging belly, whereas the juveniles are more slender.

The researchers expected to see differences in their walking ability depending on their age, however they found that differences in body shape did not alter the motion observed.

Velocity, fin rotation, axial bending and tail beat frequency and amplitude remained constant regardless of life stages, the study concluded.

“Studying epaulette shark locomotion allows us to understand this species’– and perhaps related species’– ability to move within and away from challenging conditions in their habitats,” said Marianne Porter, senior author and an associate professor at the Department of Biological Sciences, FAU’s Charles E Schmidt College of Science.

“In general, these locomotor traits are key to survival for a small, benthic [living at the bottom of a body of water] mesopredator [mid-ranking predator] that manoeuvres into small reef crevices to avoid aerial and aquatic predators.

“These traits also may be related to their sustained physiological performance under challenging environmental conditions, including those associated with climate change – an important topic for future studies.

“Investigating how locomotor performance changes over the course of early ontogeny – perhaps the most vulnerable life stages, in terms of predator-prey interactions and environmental stressors – can offer insights into the kinematic mechanisms that allow animals to compensate for constraints to meet locomotor and ecological demands.”

The results were published in the journal Integrative & Comparative Biology.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments