Sadly, the cut to universal credit isn’t going to turn people against the Tories

Labour is right to widen its attack on the government from ‘welfare’ cuts to the squeeze on everyone’s living standards, writes John Rentoul

It feels undemocratic that the House of Commons has been denied a chance to vote on the question of whether universal credit should be cut by £20 a week. But Conservative MPs, including the six former work and pensions secretaries who preceded Therese Coffey, accept that they have come to the “end of the road” of parliamentary opposition.

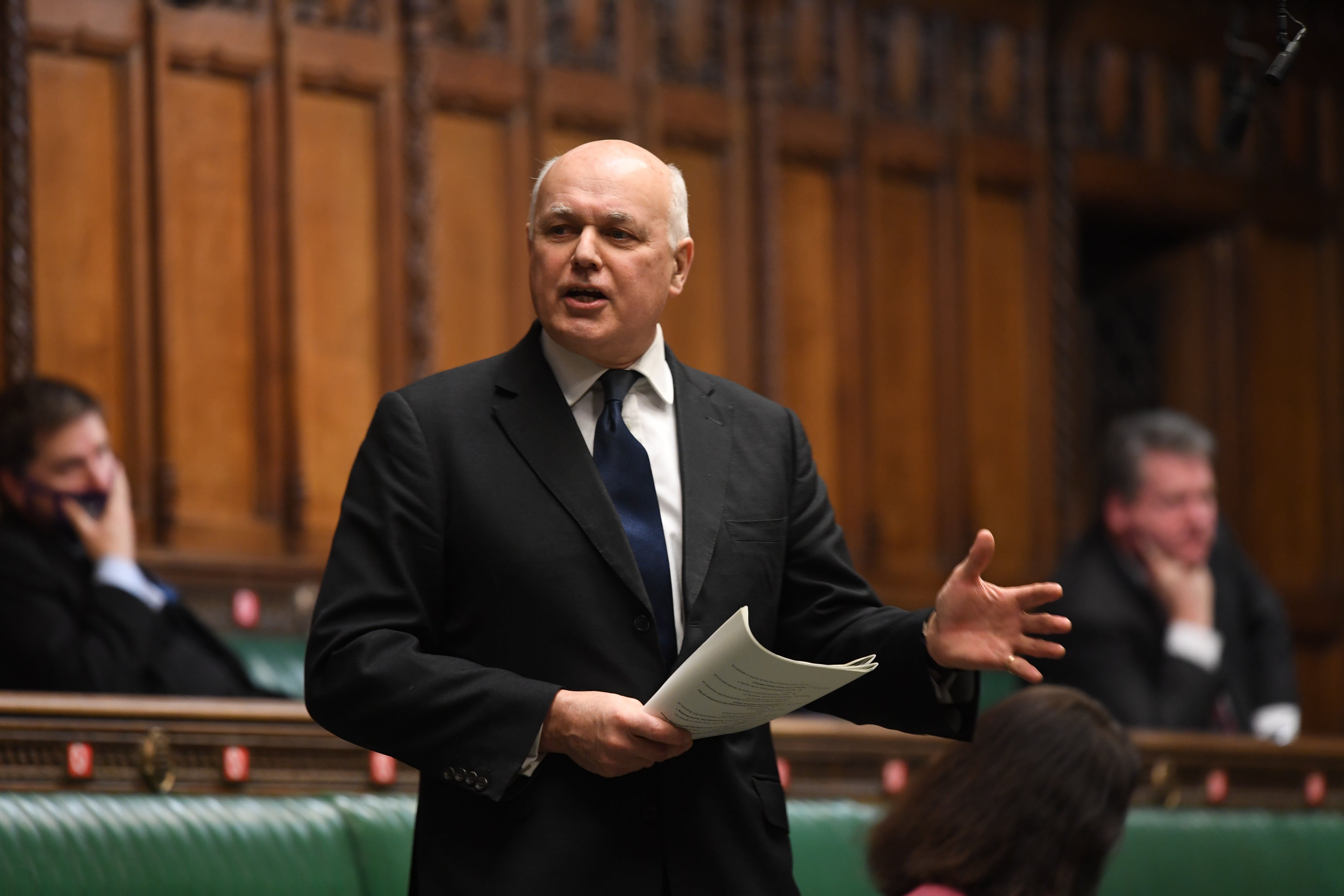

On Monday, Sir Lindsay Hoyle, the speaker of the house, refused to allow a vote on an amendment tabled by one of the six, Sir Iain Duncan Smith. Procedurally, Sir Lindsay was quite right. The amendment was trying to write a clause about universal credit into a bill about the uprating of the state pension – in other words, it was “out of scope”.

But that means we could be in the curious position of an important policy change, which has a direct effect on millions of people, coming into effect against the wishes of parliament. We cannot know what would happen if there were a vote on the change, but it seems possible, at least, that there would be more than 42 Conservative MPs prepared to vote against the whip.

That all six former secretaries of state oppose the cut is indicative of Conservative Party opinion, even if two of them (David Gauke and Amber Rudd) are no longer MPs. Many Tory backbenchers have said they agree with them, although that may be easier to say when there isn’t a vote with all the persuasive powers of the whips being deployed.

The reason we are in this strange position is that the £20-a-week uplift was a temporary measure that was legislated for early on in the pandemic, and which was always going to expire. Indeed, it has been extended once – by ministerial diktat – but Rishi Sunak has persuaded the prime minister that it must now lapse. That means people on universal credit will start to see the cut in their payments from the middle of next month.

This will be a big deal. People on universal credit know it is a big deal, even if most of the wider public seems uninterested. Will that change when the cut starts to bite? I fear it won’t.

Personally, I agree with Sir Iain and his colleagues. Universal credit was too low, and I think the £20 uplift should be made permanent. It could be paid for by a more progressive tax on property. But there is a reason universal credit was so low, which is that the Conservative government could get away with it. David Cameron and George Osborne showed their true colours in 2015 when they fought an election promising to cut welfare, and they kept that promise.

That is why I doubt that public opinion will be greatly moved when the stories of inevitable hardship start to be told. Labour repeatedly points out that four in 10 of those on universal credit are in work, in an attempt to counter assumptions about benefit claimants who “don’t want to work”. But it doesn’t seem to make much difference. Voters may tell pollsters that they agree with supporting people who are working hard and trying to do the right thing, but when it comes to it, universal credit is still “welfare” and so it is going to be a lower priority for public spending than, say, the NHS.

That in turn is why Keir Starmer chose to broaden Labour’s attack in parliament today. Given the chance of an opposition debate, which can be used only to express an opinion, rather than to change the law, Starmer today listed all the things that are going to squeeze living standards for everyone, not just for universal credit claimants.

Labour’s motion started with the cut in universal credit, but then expressed concern about “the rise in national insurance contributions for low and middle income workers, increases in council tax, the freezing of the personal income tax allowance from April 2022, the increasing cost of household energy bills…” and so on, ending with “rising prices resulting from the supply chain disruption caused by worker and supply shortages”.

Electorally, this has to be the right approach. The cut in universal credit is now only part of a fiscal retrenchment that is bound to be called the new austerity even before next year’s tax rises take effect. Boris Johnson may be desperate to avoid the a-word, but it won’t be up to him. That is what it is going to feel like for a majority of the population, as prices rise, especially of energy, and the NHS, already in crisis, gets a winter crisis on top. When Kwasi Kwarteng, the business secretary, is reduced to denying that the lights will go out this winter, the prime minister’s boosterism is starting to wear thin.

With the government having run out of taxes to raise, the return of inflation and the NHS in deep trouble, some echoes of the past are unavoidable. They do not bode well for the popularity of an incumbent government. It is a shame that the cut in universal credit won’t itself turn public opinion against the Conservatives, but when it is combined with everything else that is about to happen to the living standards of people on or around average incomes, it is hard to see how Johnson, the escapologist of recent British politics, is going to get out of this one.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments