Enough of the pessimism – we need the Olympics now more than ever

As far as hard economics and hard health policy are concerned, the case against the games looks overwhelming. But I think it is wrong, writes Hamish McRae

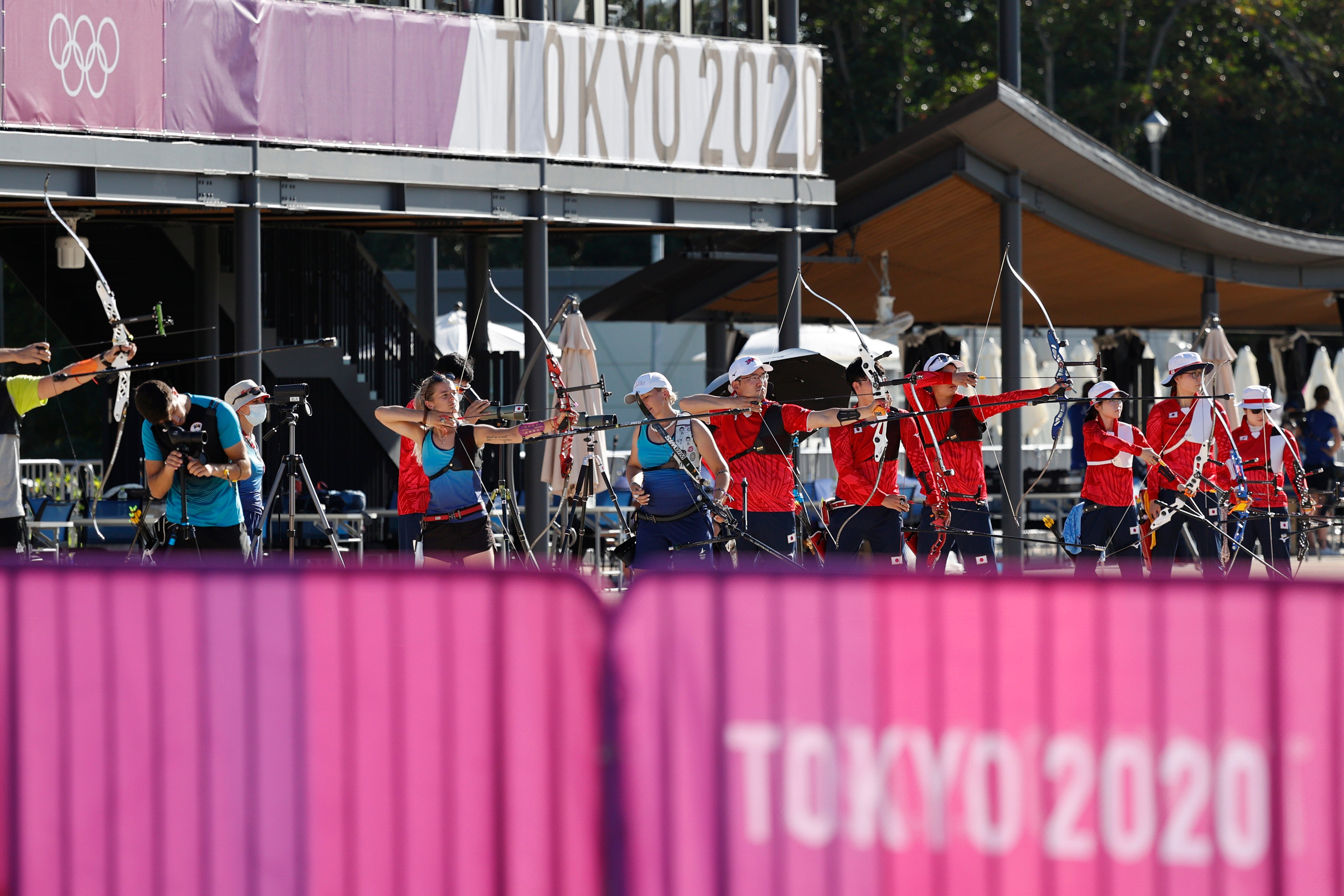

It will be the strangest of Olympics that opens on Friday. No spectators at most of the events; medals handed out on a tray instead of hung over athletes’ necks; no high fives. It will be a sombre, muted, troubled Olympics for our troubled times.

The arguments against holding it are manifest. Tokyo is under a state of emergency. According to an Ipsos opinion poll, only 22 per cent of Japanese people think it should be held at all. The support is a little higher in other countries but overall it is only 43 per cent.

All the old arguments come out. One is cost. The games are only going ahead because so much has been invested in them – an estimated $15.4bn, though now that is expected to be exceeded. Another is that the facilities may be fine for the event, but are not appropriate for long-term sports use. Rio de Janeiro is still struggling to make good use of the facilities it built for the last games five years ago.

Still another is the more general criticism that is it irresponsible to hold the games in the middle of the most serious pandemic for a century – so what, if one person can jump higher than someone else, when inevitably more people will catch a horrible disease? Far from being a celebration of the defeat of the virus, as many had hoped it would be, the games may mean it will take longer to crush it.

So, as far as hard economics and hard health policy are concerned, the case against the games looks overwhelming. But I think it is wrong.

Start with money. The investment sounds huge, and since there will be no spectators at the main events, the losses will be massive too. TV rights will not compensate for the lack of ticket sales. But in the totality of the Japanese economy, the third largest in the world, this is tiny. Japan’s GDP is roughly $5,000bn. The odd $20bn either way barely registers. There is a huge economic issue in Japan, which is that growth has stagnated for 25 years. But that is nothing to do with the Olympics.

Next, take the legacy. Here Japan can point to the success of the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, which transformed the country, partly by building facilities and sprucing up the capital, but also by giving Japan back its self-confidence after the defeat in 1945. It has elaborate plans to learn the same lesson that an event can be a spur to an entire nation. Now it is true that the pandemic has given a severe blow to that ambition, but the physical investment is there and going ahead with a low-key games is surely more likely to make for a positive legacy than cancelling them.

And the more general arguments against these Olympics? The best way to counter those is to point to what the games do not just for the host country and the participants, and certainly not for the sponsors, the media, and the other businesses that are trying to make money out of the whole shebang. It is what they do for a world that desperately needs to find ways to strengthen the glue that binds humankind together.

If that sounds pretentious, consider this. The games have always been political, indeed so political that countries have boycotted them. The US did so for the 1980 Moscow Olympics, in protest at the Soviet Union’s refusal to withdraw troops from Afghanistan – something that seems odd now, given what happened subsequently. The US did not need a nudge from Russia when it decided to pull its own troops from Afghanistan, an exit completed earlier this month. The USSR did a tit-for-tat boycott for the Los Angeles Olympics four years later.

They have always been displays of nationalism. Remember how Britons cheered at the excellent tally of medals won by the GB team, when it came in number three behind only the US and China in London in 2012?

And I am afraid there have always been issues about performance-enhancing drugs. The first recorded case was in the 1904 summer games in St Louis, when the British-born American marathon runner Tom Hicks was given a dose of strychnine, brandy and egg-white by his coach at the 22-mile mark to spur him to victory. He collapsed after the line – but kept his medal. Drug use was not something pioneered by the post-war USSR and its eastern European cohorts.

But despite all this, the dream survives. It is big enough to surmount the politics, the nationalism and the drug use. To win is wonderful, but that by definition can only be for the few. There are some 11,500 competitors for the Olympics and 4,500 for the Paralympics. For the thousands who do not win medals, their dream is just as valid, indeed almost more so. Our lives are enhanced by our modest successes, but we all know that what really matters is to try to cope as best we can with whatever is thrown at us.

A lot has been thrown at all of us these past 18 months. The Tokyo Olympics remind us that the world collectively is coping as best it can with a very difficult set of pressures. Those 16,000 competitors, every one of them, deserve our applause.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks