How western greed fuelled Putin’s rise and enabled his war machine

The west has been the architect of a corrupt world order in which rich and powerful men like Putin – said to be a multibillionaire in his own right – feel they can get away with anything, writes Borzou Daragahi

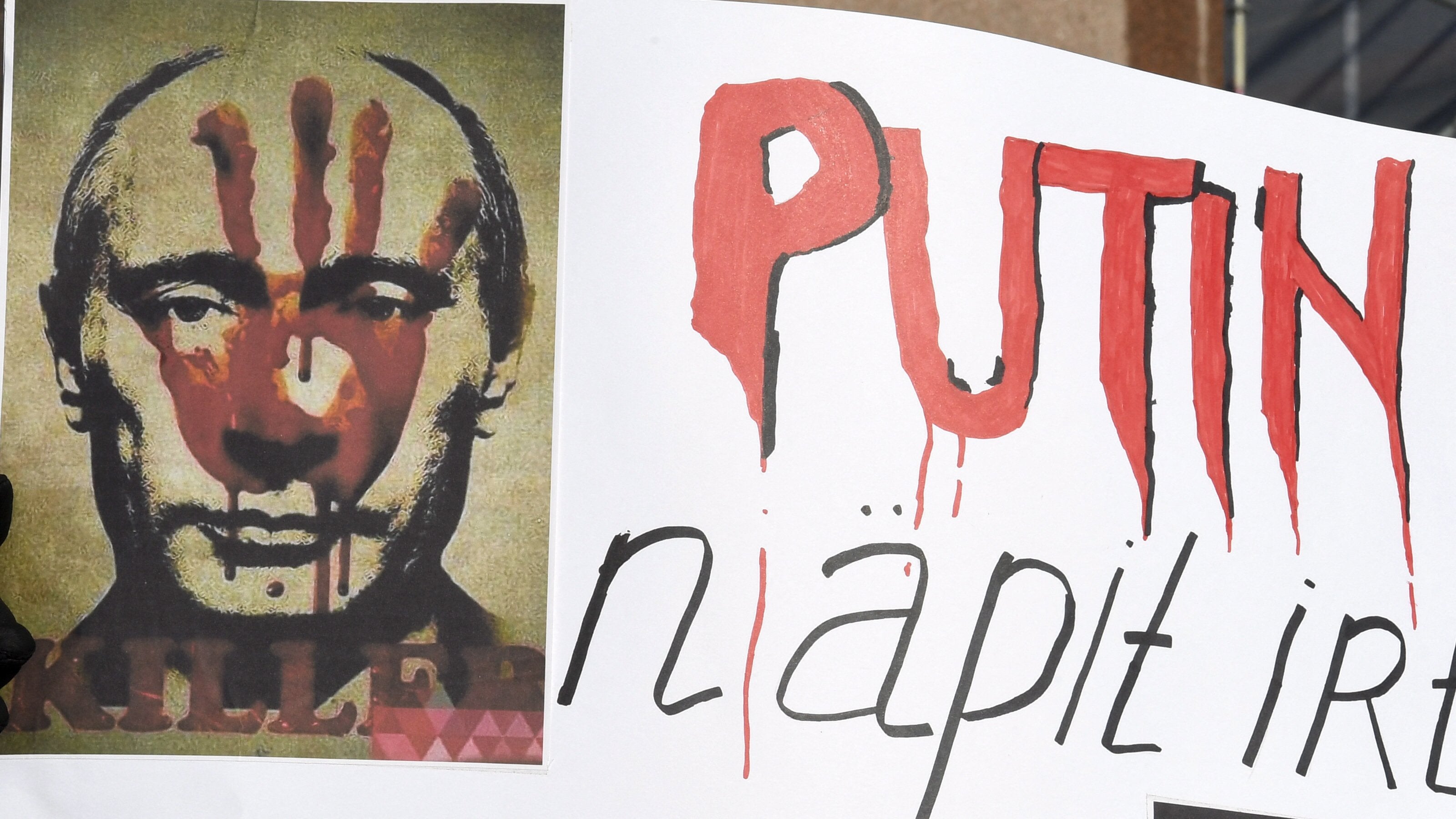

Governments around the world are rightly condemning Vladimir Putin’s illegal and completely unjustified invasion of Ukraine – a peaceful nation of 44 million that has never posed a threat to its neighbours, and has been struggling to emerge from centuries under the yoke of foreign powers and decades of corruption and misrule.

Draconian sanctions have been imposed, and some Russian banks are now barred from the Swift messaging system that is a backbone of efficient contemporary international banking.

But those same nations now condemning Russia’s attack on Ukraine played a major role in Putin’s rise and the growth of his outsized ambitions, as well as a massive war chest worth hundreds of billions of dollars. There have been policy blunders born out of laziness and ideological rigidity, and inaction spurred by a lack of imagination. Driving all of this, however, has been greed.

The mistakes began just after the Soviet Union collapsed. Western governments and institutions, including the International Monetary Fund, along with numerous predatory financial players contributed to the Weimar-like political and economic chaos in 1990s Russia.

During those years, following bad western advice peddled by bankers and consultants getting rich in Moscow, Russia’s economy plummeted. Life expectancy and birth rates collapsed. Crime and gangsterism pushed the country to embrace ex-KGB man Putin as the man who vowed to impose a “dictatorship of law” in the fateful 2000 elections.

Western nations mostly ignored his human rights violations and crackdowns on freedoms of the press and civil society as he consolidated his rule. Sure, there have been statements of “concern” after arrests of peaceful protesters and righteous condemnations from podiums at press conferences. But none of that stopped countries like the United Kingdom, France and Switzerland from embracing the flow of dirty Russian money from oligarchs associated with Putin’s inner circle into their real estate and banking sectors.

Instead of ramping up renewables and reducing energy consumption, Europe has been content to buy cheap gas from Russia, lining Putin’s pockets and bankrolling his rapid upgrade of the country’s military forces over the last two decades. Former German chancellor Gerhard Schroeder joined Russian energy giant Gazprom shortly after leaving office in 2005, and began pushing for Baltic Sea pipelines whose sole purpose seemed to be bypassing Ukrainian, Polish and Baltic nations upon which Russia has historical claims.

And even after Russia attacked and disfigured Georgia in 2008, Putin was allowed to remain in the G8, welcomed by western leaders as a respected statesman at its summit in Italy the following year, where his bombing of the Caucasus nation was not even an agenda item. In the aftermath of the Georgia attack, his family was even reportedly able to build a life of leisure in the upscale French resort of Biarritz.

Finding an open door after his bombing campaign and seizure of the regions of South Ossetia and Abkhazia, Putin continued to push forward. The 2014 attack and invasion of Ukraine and annexation of Crimea finally convinced the G7 to push Putin out. But gas and oil sales continued robustly. Russia’s horrific war crimes in Syria, which included devastating aerial bombardments of schools, hospitals and residences that continue to this day, should have shown the whole world who Putin was.

Instead, despite his relentless and maniacal onslaught against Syrian civilians, blue-chip firms such as Morgan Stanley, Apple, PepsiCo, Procter & Gamble, McDonald’s and General Electric continued to operate in Russia.

Even a campaign of assassinations abroad using weapons of mass destruction, he was still allowed to host the 2018 World Cup, a spectacle which served as a political boost for Putin.

Putin’s robust support for Alexander Lukashenko’s brutal crackdown in Belarus after he stole the 2020 election should have served as another wake-up call, as should his grotesque poisoning of dissident Alexei Navalany. But that year, Russia sold Europe 175 billion cubic metres of natural gas.

Thanks largely to western hunger for Russian gas, Putin’s Central Bank has accumulated a record $630bn in foreign reserves. And despite the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, Russia boasted a trade surplus of $120bn last year – its largest ever.

Last summer, Putin announced Russia’s claims on Ukraine and by implication other former Soviet satellite states in an unhinged but prophetic essay that should have warned the world of his intentions. But even then there was nothing, absolutely no response from world powers. To be fair, even the Ukrainian president, Volodymyr Zelensky, downplayed the essay.

On the other hand, experts say the Kremlin-linked oligarchs got the message, and were given plenty of time to secure their ill-gotten wealth. “For these oligarchs this has been coming for months if not years,” says Michael O’Kane, an expert on sanctions law at the London firm Peters & Peters.

“Temperatures have been turning up for some time. They will have gotten their liquid assets out of the US, UK and Europe and into somewhere safe. They will have restructured their corporate assets so they are not obviously owned by them. The sanctions come very late and many of them will have taken steps to protect themselves.”

To keep up to speed with all the latest opinions and comment, sign up to our free weekly Voices Dispatches newsletter by clicking here

Impending sanctions on Russia’s Central Bank will complicate Moscow’s ability to spend its cash. But most of the sanctions imposed so far have been on high net-worth individuals believed to have benefitted from the Ukraine debacle. O’Kane described such sanctions as “signalling” exercises that will have little impact on Russian policy. “When they find out that their children can’t go to school in the UK, are they really going to go to Putin and say, ‘You have to pull your troops back because little Vlad can’t go to Eton?’”

Even now, the flow of gas and barrels of oil have yet to stop, and a few countries like Switzerland, which is the headquarters of the Nord Stream pipelines, have been reluctant to join in any sanctions.

More broadly, the west has been the architect of a corrupt world order in which rich and powerful men like Putin – said to be a multibillionaire in his own right – feel they can get away with anything.

“In a system without checks and balances, Russian elites are emboldened to act against international law,” Daniel Eriksson, the CEO of the anti-corruption NGO Transparency International said in a statement. “Secrecy laws and lack of oversight from authorities have allowed the Russian elite to hide their wealth, funding corruption back home and abroad.”

In Putin’s writings and speeches, he frequently describes the west as so greedy and decadent that it would eventually destroy itself from within. Looking at western behaviour toward Russia over the last three decades, it is hard to disagree.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments