Mea Culpa: Mister the Lord as he then was not

Questions of language and style in last week’s Independent, reviewed by John Rentoul

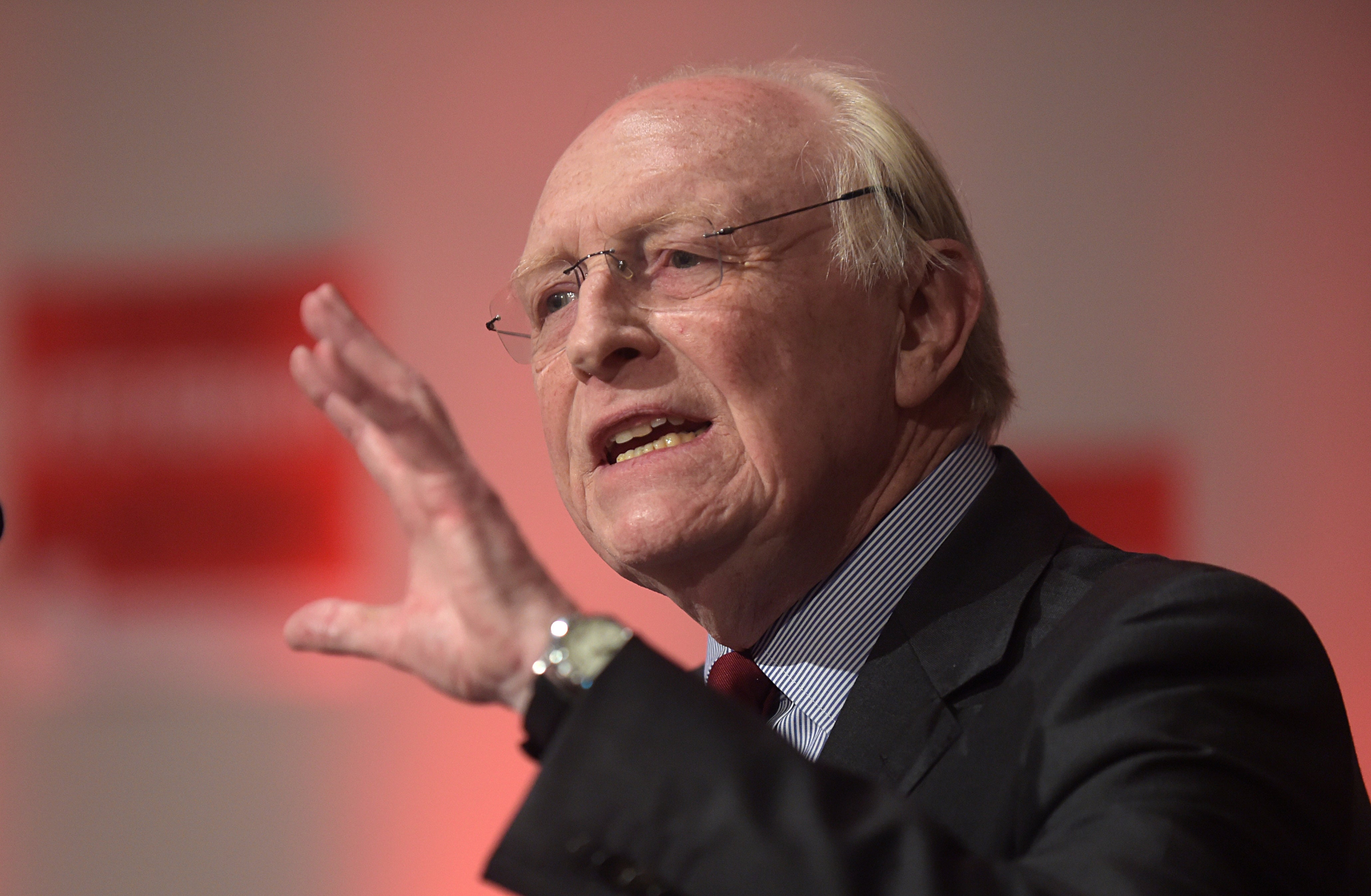

We referred to Neil Kinnock, the former leader of the Labour Party, in Thursday’s editorial about Sir Keir Starmer’s pitch to the voters. On the second occasion, we said: “The then Mr Kinnock was a genuine man of the left who found himself, mostly for electoral purposes, shedding principles and crabbing towards the right.” We called him “the then Mr Kinnock” because our usual style for a second mention would be “Lord Kinnock”, except that he wasn’t a lord when he was Labour leader.

I think in this situation we should just call him “Mr Kinnock” because that is what he was at the time. That he is now a lord was irrelevant to the argument in the editorial – indeed, we didn’t refer to his peerage at all, except by implication in that awkward “the then Mr” formulation.

We also got our tense wrong in saying that he “was a genuine man of the left”, which made it sound as if he is dead. He is very much alive and offering a voluble and entertaining commentary on politics. We could have said he “had been” a genuine man of the left.

Wrong not wrong: We published an interesting first-person account on Monday by a woman who had faced the choice posed by a famous TikTok video. Our headline read: “I literally had to choose between ‘man or bear’ in the wild – and I chose wrong.”

Many readers over a certain age will have instinctively “corrected” that in their heads to “wrongly”. But wrong is not wrong, it is simply different, and a usage that has spread recently to become standard for many people. My usual argument is that we should avoid newer forms and stick to older conventions, to avoid distracting, annoying or confusing any significant body of readers. The “flat” adverb wasn’t used by the writer herself, whose style was fairly traditional, so there would be a case for using “wrongly” in the headline.

But in this case, I think there is an argument the other way. The bluntness of “I chose wrong” gives the headline a colloquial directness, and I doubt if it would have put anyone off reading what was a good article. Language changes, and eventually we have to change with it.

Round about: In Tuesday’s report about the alleged spies from Hong Kong we twice mentioned “the Yorkshire area”. As a Yorkshireman, Mick O’Hare wanted to know more. Was this actually a way of saying Lancashire, in the way an estate agent might refer to somewhere that is near Yorkshire but not as nice?

Stop lifting: Mick O’Hare also drew this headline to my attention: “Police are not interested in shoplifting, says M&S boss.” Thank goodness; it would seem that there are quite enough shoplifters already without them. Later versions of the headline had the word “tackling” inserted before “shoplifting”.

The same article also mentioned, twice, that the company had spent money on “preventative” measures. This is a long word that we use quite often, especially in our health reporting. As Richard Thomas points out, “preventive” is shorter and therefore better.

Teach the teachers: A headline on Thursday said: “Schools to be told not to teach sex education to children under nine.” This did not make sense, as Brian Mathieson wrote to say. People who are “taught sex education” are usually teachers, during their training. Children receive sex education or are taught about sex and related matters. The headline was changed to say: “Schools to be told not to deliver sex education to children under nine.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments