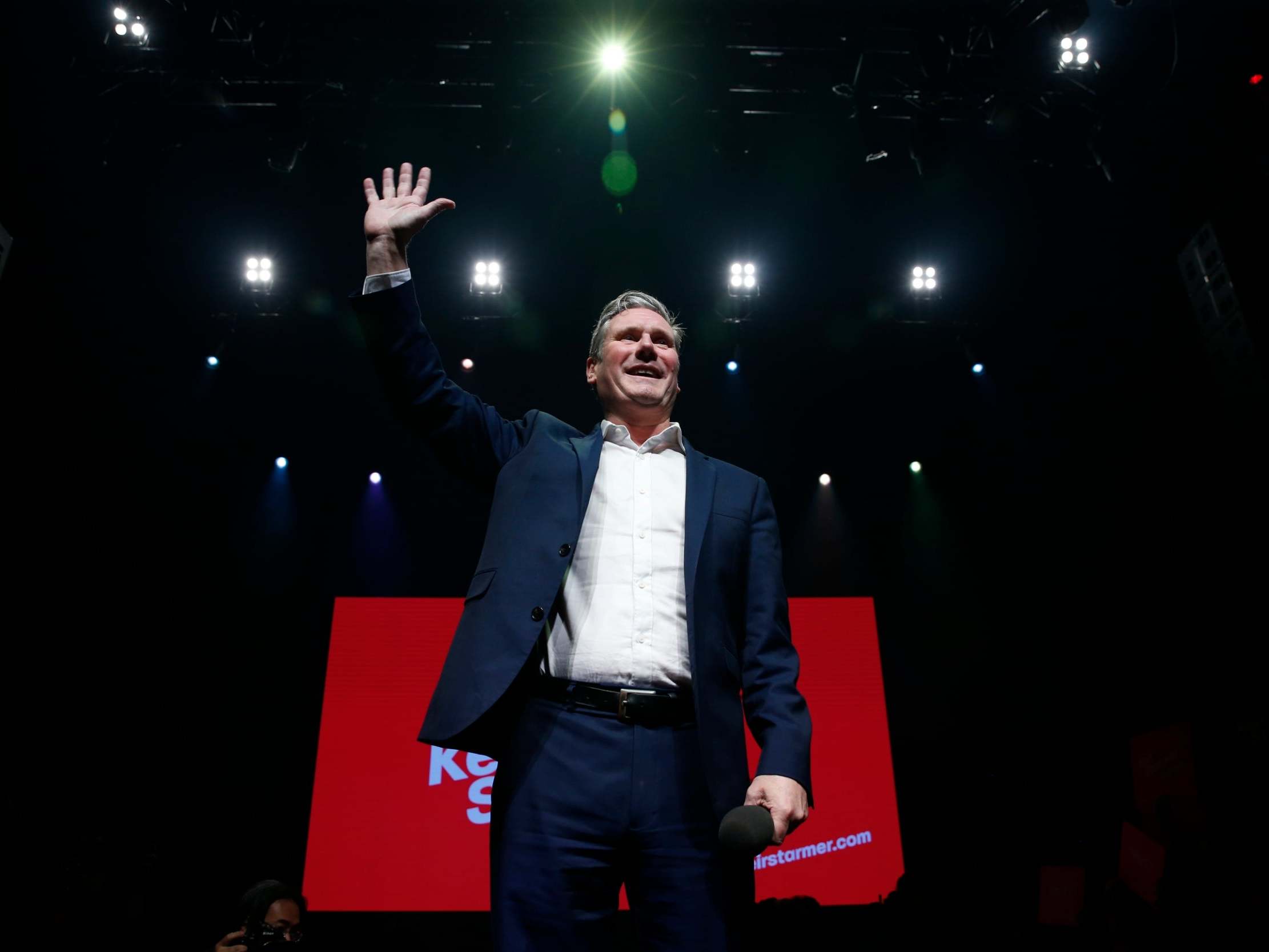

Neither Blairite nor Corbynista, Keir Starmer is the only hope of uniting faction-ridden Labour

The new Labour leader is bang in the middle of the party’s centre of gravity, making him the man to lead it

Confirmed as new Labour leader on Saturday, Keir Starmer won because enough of the party’s members decided they wanted to win after four painful electoral defeats. Most members like Corbynism, but have recognised that ideological purity is not enough.

The 57-year-old, who had been shadow Brexit secretary, is bang in the middle of the party’s centre of gravity. Having a leader on the far left of that spectrum didn’t hold the party together; nor would it work if a Blairite succeeded Jeremy Corbyn.

Starmer benefited from a hesitant campaign by Rebecca Long-Bailey, second-turned-first choice as carrier of the Corbyn flame after Laura Pidcock unexpectedly lost her seat. Lisa Nandy made more impact than Long-Bailey by challenging the party to answer difficult questions, but she started too far behind and relatively unknown. Perhaps Nandy paid the price for her principled decision not to serve in Corbyn’s shadow cabinet after the failed coup against him in 2016. Like Nandy, Starmer resigned to join the rebellion; unlike her, he returned to the front bench.

It looks like the right career decision now. Without criticising Corbyn, Starmer led Labour’s crab-like move towards embracing a referendum on the Brexit deal, against the leader’s initial wishes. Starmer was in tune with Labour’s pro-EU membership on the one issue that Corbyn was not. It marked him out as a contender if Labour lost the election, and a perfectly placed one. However, perceptions of Starmer as “another pro-referendum London MP in a suit” (albeit a smarter one than Corbyn’s) leave him with some convincing to do in the pro-Leave seats that turned Tory in December in the north and Midlands.

Allies insist that Starmer was being true to himself, but they concede he has an ambitious streak. They say the human rights lawyer did not get a taste for politics until he advised the Northern Ireland policing board on the Good Friday Agreement, after which he applied successfully to become director of public prosecutions. But other friends believe he always wanted to be prime minister, even comparing him to Michael Heseltine, who famously scribbled his desired destiny to be PM by the age of 55 on the back of an envelope.

Starmer will be less cautious in office than his safety-first leadership campaign suggested. Frontrunners often get caught, so his caution was justified. However, he will now have to take some difficult decisions, weeding out hardline Corbynistas from Labour headquarters and limiting their strength in the shadow cabinet, while paradoxically preaching unity and an end to the factionalism that scarred the Corbyn era.

His friends admit that he is “not a clubbable resident of the Westminster village”, and something of a loner. He remains an enigma to many in his party, let alone the country. Some left-wingers view him as a closet Blairite who will “do a Neil Kinnock and purge the left”. Others describe him as “continuity Ed Miliband”. Some on the Labour right didn’t back him because, they claim, he didn’t stand up to Corbyn, and pandered unnecessarily to the hard left in the contest by embracing its policy agenda.

The real Starmer is neither Blairite nor Corbynista; he’s on the soft left, which offers the only hope of uniting the faction-ridden party. His time as a lawyer proves he is a man of the left. As one fellow QC put it sheepishly: “He could have made a lot of money at the bar like the rest of us, but preferred pro bono cases in line with his own principles.”

Incoming party leaders usually have a small window of opportunity to make an impact on the public, and first impressions often stick. Starmer does not like doing the personal stuff but will have to accept that voters need to know more about him and his family.

It won’t be easy to make an impact amid the coronavirus crisis. For now, Boris Johnson and the government enjoy strong public support. But if there’s one word that friends and foes alike use about Starmer, it is “forensic”. It’s the right time for such scrutiny of the government, and for Labour to be more critical as ministers falter over testing.

Starmer has a difficult balancing act; he must avoid playing party politics when the public is desperate for the government to succeed. He will provide the statesmanship and gravitas that Corbyn lacked. But he might have an early dilemma: it is possible Johnson will try to spread the blame for any mistakes over the coronavirus by inviting Starmer to join meetings of the Cobra emergency committee. It would be an offer Starmer could not refuse, but it might make constructive criticism harder.

Some senior Labour figures view Corbyn’s departure with relief and Starmer’s arrival, amid a possible sea change in politics in Labour’s favour after the coronavirus, as the moment when victory at the next election becomes not just possible but likely. “The tide will now flow in our direction,” one said.

In normal times, leader of the opposition is a tougher job than prime minister. Not now – but the old rules will return at some point, and the next election is a long way off. Labour’s optimists should not get carried away. Starmer’s prospects may depend on matters beyond his control, notably the public’s final verdict on Johnson’s handling of the crisis.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments