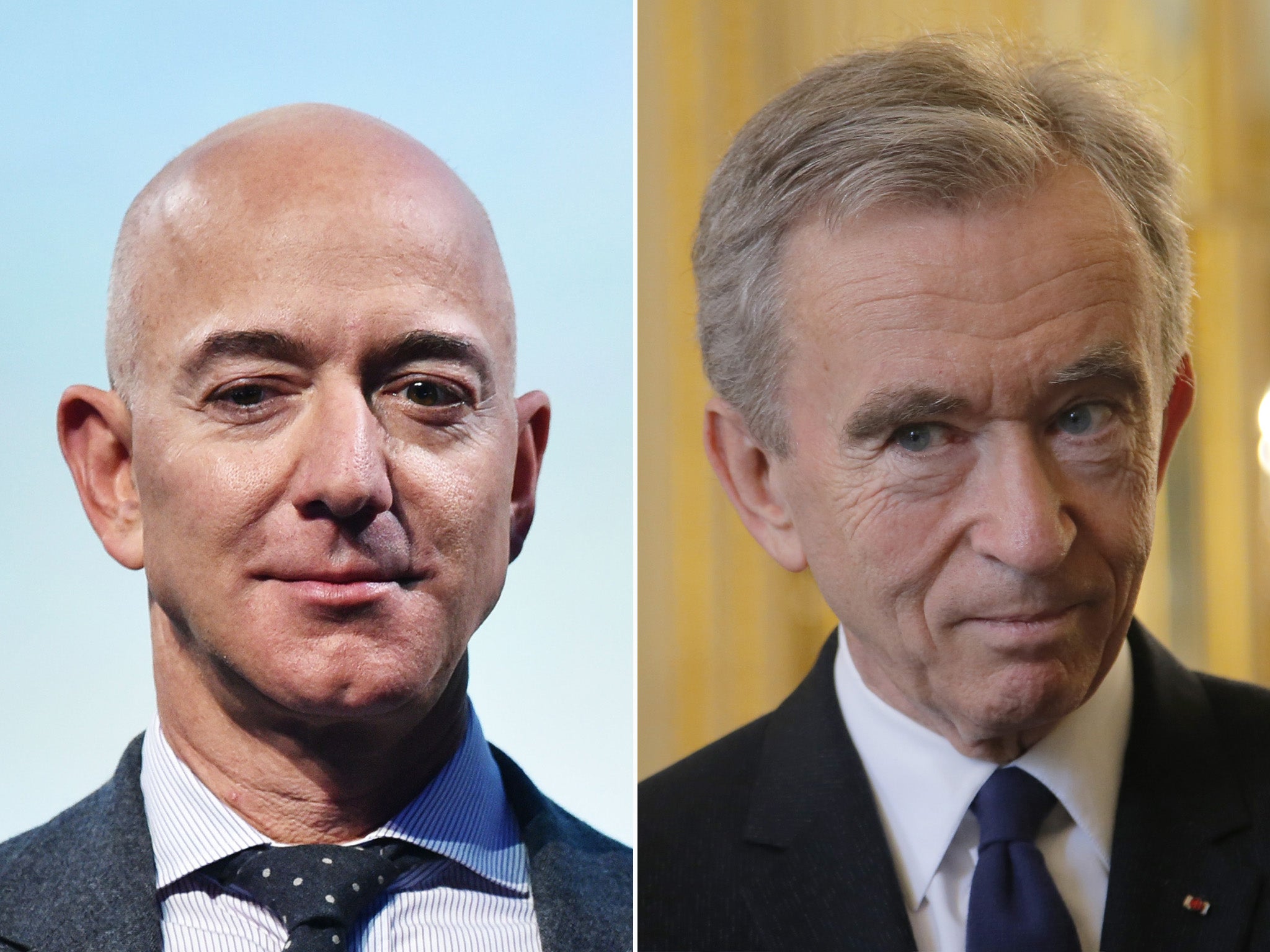

Behind Jeff Bezos and Bernard Arnault tussling to be the world’s richest person lies a bigger issue

There has always been a fascination about wealth, and this little battle is a fun story. But it also plays into the question of what will be the dominant industries of the next decade, writes Hamish McRae

On Friday Bernard Arnault, chair and chief executive of the French luxury business LVMH, was again the richest person in the world. He and Jeff Bezos, founder and CEO of Amazon, have spent the past few days swapping the pole position in the global wealth league table.

The reason for the tussle is that the share price of each company has been nudging up and down, and though LVMH is a less valuable company – it was worth €332bn (£277bn) on Friday against Amazon at $1.63 trillion (£1.15 trillion) – Arnault has a larger personal stake than Bezos.

There has always been a fascination about wealth, and this little battle is a fun story. But behind it is something much more important. It is the question: what will be the dominant industries of the next decade? Will they be the high-tech giants of America, the current winners of this particular game, or will they be something else?

If you think back even five years, it was not clear that Amazon would dominate in the way it does now. True, Apple and Microsoft were dominant in their businesses, but it wasn’t so evident that Tesla could be worth more than the next six car companies put together, as it was at the end of last year.

Now look at luxury. What France has achieved is astounding. It has six of the world’s top 10 luxury brands – according to a number of outlets – including the top three, Louis Vuitton, Chanel and Hermès. It is extraordinary that any single country should dominate the luxury business in this way, but even more extraordinary that this dominance should date back to the 17th century. Louis XIV’s minister of finance, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, is best known for his quip: “The art of taxation consists in so plucking the goose as to procure the largest quantity of feathers with the least possible amount of hissing.”

But he also observed in 1665 that: “Fashion is to France what the gold mines of Peru are to Spain.” A reflection on way the country generated its wealth.

Italy has luxury brands, with Gucci and Prada in the top 10. Switzerland has Rolex. The UK has Burberry. But the US, the world’s largest economy, is not really in the game. Nor is China, the world’s second largest. Nor is Japan, number three.

Some people are sniffy about luxury. It is not easy to defend billionaires spending their money on hand-built yachts when their businesses are all too often built on work practices that many of us find unpalatable. Some of the adverts in the glossy magazines for watches that cost upwards of $10,000 a pop make many of us feel uneasy.

But the world is as it is, and one person’s luxury is another person’s necessity. The plain fact is that the global luxury business is booming, thanks largely to the rise in asset prices more generally, and to the growing ranks of the rich in China and the rest of Asia.

So just as the story of Jeff Bezos symbolises the rise of US high-technology, so the tale of Bernard Arnault is a manifestation of the importance of European, and particularly French, luxury. But it is more than that. It is one of the competitive advantage of the US vis-à-vis that of Europe. Which will be more durable?

Actually, they both will – but with the proviso that China can imitate the US (Tencent, Alibaba and so on) whereas I don’t think it can create luxury on the scale of Europe. If this is right, then there are reasonable grounds to hope that over the next 30 years or so Europe will manage to be a reasonably successful economic region. Of course the French economy is much more than luxury, just as that of Germany is much more than engineering or of the UK much more than finance. The economic strength of Europe lies in its diversity: different bits are good at different things.

That leads to a further conclusion. The success of Arnauld lies in his running an established set of businesses really well. If you can create new businesses that is wonderful, and the US genius for innovation will ensure it carries on along its restless economic march. But people want established products and services as well as innovative ones.

Being outstandingly good at a particular activity – as France has in luxury products for 400 years – is worth celebrating too. It creates a lot of jobs, many rather better than working in an Amazon service centre, and Arnault has done all right too.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks