‘How old are you? 12?’ The day I got ticked off by fiery Glenda Jackson

She wasn’t afraid to be angry in a world that too often expects women to be obliging and demure, says Sue Gyford

Hampstead, 2003. New Labour reigned, opposition to the Iraq war raged, and Glenda Jackson was MP for Hampstead & Highgate.

In the greyest corner of the neighbourhood, I was wedged into a scruffy office in Swiss Cottage, chief reporter at the Ham & High – the local newspaper for a part of London so stuffed with big-hitters that it had Michael Foot knocking out the book reviews.

It was a novelty to scrawl a couple of “famous” MPs’ numbers into my contacts book after 18 months covering Islington, a borough where Granita was still wedged firmly on Upper Street, but Blair’s departure for Downing Street was already ebbing into memory, and a little-known, lifelong backbencher (as I was convinced at the time) called Jeremy Corbyn was MP.

Two MPs represented my new patch – Glenda, and Frank Dobson for Holborn and St Pancras. A truly mixed bag for a young reporter: Frank was endlessly avuncular, ensconced in his flat opposite the British Museum – right on patch and quick to return calls, in a tone that suggested he’d been waiting to hear from you.

Glenda was sharp in mind and manner, raising a few eyebrows for living in Blackheath, south of the river and some miles from her constituency. But, in a place where you could barely walk to the corner shop without tripping over an author, artist, actor or activist, very much at home in Hampstead, in spirit, if not in residence.

Our first encounter was face-to-face, and cordial. After an event in Hampstead, where I needed to grab some lines from her, she invited me warmly to depart with her, and we stood on the corner of Heath Street as I scribbled in my book and she gave me what I needed before dashing off to her next appointment.

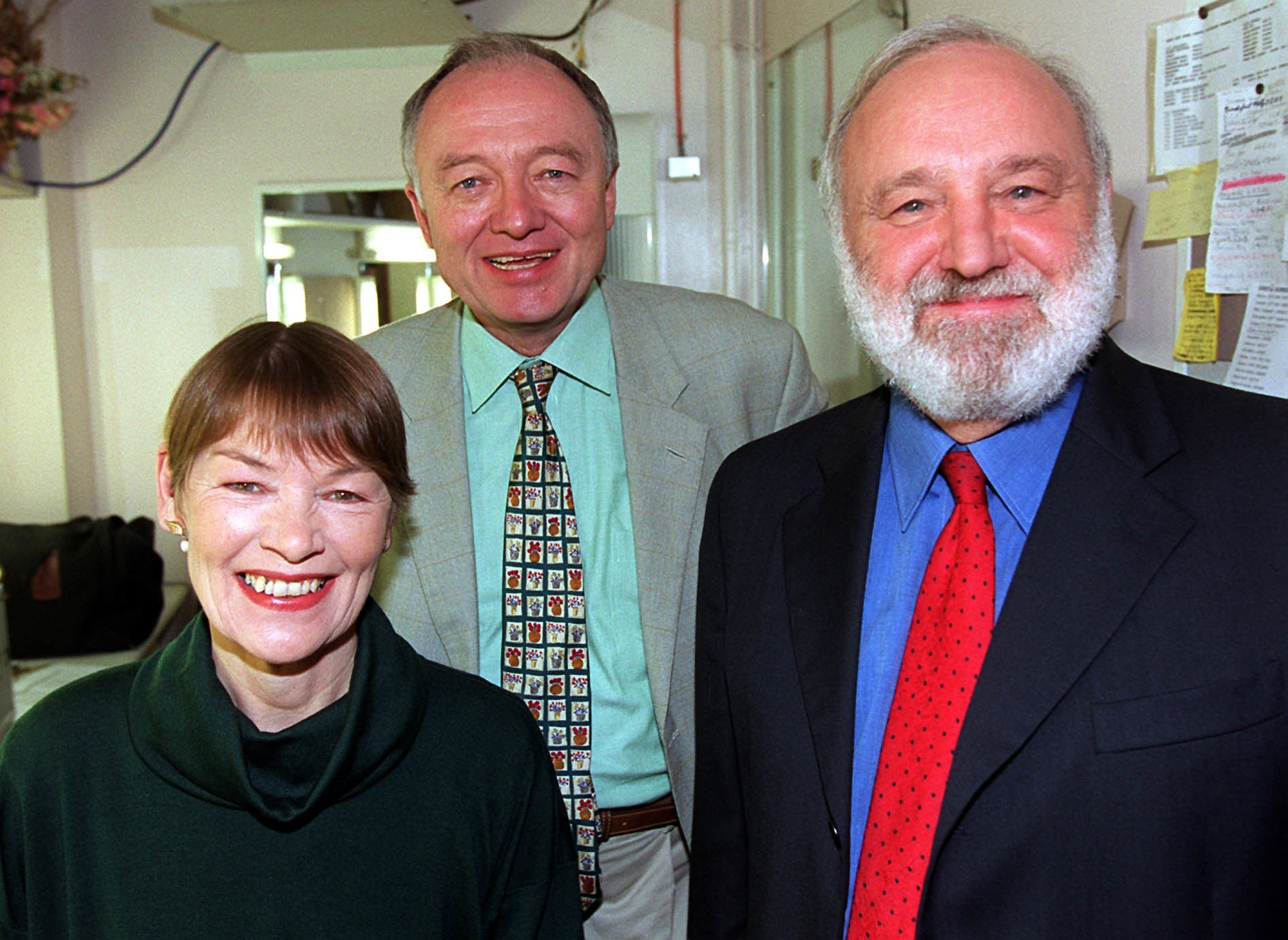

But it wasn’t always so easy – no matter how many times I called her at the Commons, she’d speak to me as if we’d never crossed paths. As opposition to the Iraq War grew fiercer, she and director Peter Brook were scheduled to lead a rally at the Camden Centre in St Pancras.

I was told to call her for a chat, and to ask if she’d ever worked with Brook before. As the news editor said, “she’s always saying she doesn’t want people harping on about her acting career now that she’s a politician, so she can’t complain if we don’t know”.

She and Brook had of course – I now know – been great collaborators on many projects including the RSC’s 1966 anti-Vietnam show US.

However, in those pre-internet days the only way to find something out quickly if you didn’t already know it, was to ask. And so I did.

There was a terse pause.

“Oh for God’s sake, how old are you? You sound about 12,” she spat back.

She knew her power – as all leading ladies do – and how to deliver a piercing verbal dart, and it took all I had not to quake as it struck.

Instead, her verve infected me and I snapped right back: “Well, why don’t you just patronise me then, Glenda?”

“All right then, I will,” came the reply with nothing short of glee, and I suspect we both came away feeling like we’d won the joust.

It was an exchange that epitomised her fiery charm – passionate, direct, not afraid to be angry in a world that all too often expected women to be obliging and demure.

First elected to the Commons in 1992, she was joined five years later by the so-called “Blair’s babes”, the patronising, sexist moniker given to the influx of female Labour MPs, and it’s hard to imagine anyone less deserving of such a flimsy label – not least because she was ultimately one of the administration’s great rebels.

A trawl through my hoarded Ham & High cuttings from the era shows her in February 2003 holding back from calling for Blair’s resignation over Iraq, as the Hampstead Labour Party branch called for him to go. But by July of the same year she’d swung behind them and, as well as demanding he quit, ended up one of only 12 Labour rebels who defied the whip and voted for an inquiry into the war.

But it was not just matters of state. She appears in cuttings weighing in on proposed changes to licensing laws, opposing hunting with dogs, calling for a review of right-to-buy. She even copped some flak for appearing in an advert for The West Wing (lending her political support to President Jed Bartlet’s bid for re-election).

A woman who was fiery indeed, but whose intensity was fuelled by principles, and a fearlessness that she brought to bear on her deep sense of political duty, as much as she did to her work on stage and screen.

Sue Gyford was chief reporter for the Hampstead & Highate Express

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments