Powerful men who have escaped scrutiny may well be alarmed by the Maxwell verdict

Prosecutors and judges habitually brandish the spectre of draconian sentences in the hope that the defendant or, in this case, the guilty individual, will spill the beans on related cases, writes Mary Dejevsky

For a legal case of some complexity, the prosecution of Ghislaine Maxwell was done and dusted with surprising dispatch. After a trial lasting less than three weeks, the jury spent just 40 hours on its deliberations before returning five guilty verdicts and only one acquittal on the charges of grooming and sex-trafficking before it.

Members of her family – who had been in court for the duration – seemed taken aback by the verdicts, and announced her intention to appeal against convictions that could mean she spends the rest of her life in prison.

The most immediate question now will be whether the unanimity of the verdicts and the likely severity of the sentence will precipitate the sort of plea-bargaining that is common in the US justice system.

Prosecutors and judges habitually brandish the spectre of draconian sentences in the hope that the defendant or, in this case, the guilty individual, will spill the beans on related cases in return for more lenient treatment.

Seen from the European side of the Atlantic, this is a highly dubious practice that can put innocent people in prison – but for Maxwell, as for so many before her, it could offer a tempting lifeline.

To her credit, Maxwell resisted any plea-bargaining before and during her trial – though whether this was on principle or because she was counting on acquittal must be an open question.

But the prospect of multiple life-sentences could change her mind – which is why some powerful men who have hitherto escaped scrutiny in the United States may now be alarmed, as well as a certain member of the British royal family.

Could Ghislaine Maxwell provide the missing link between the Queen’s second son, Prince Andrew; the late financier and convicted paedophile, Jeffrey Epstein; and Virginia Giuffre? She is the woman who is suing the prince, claiming that, as a teenager, she was forced to have sex with him at Maxwell’s home in London and suffered abuse at two other locations belonging to Epstein.

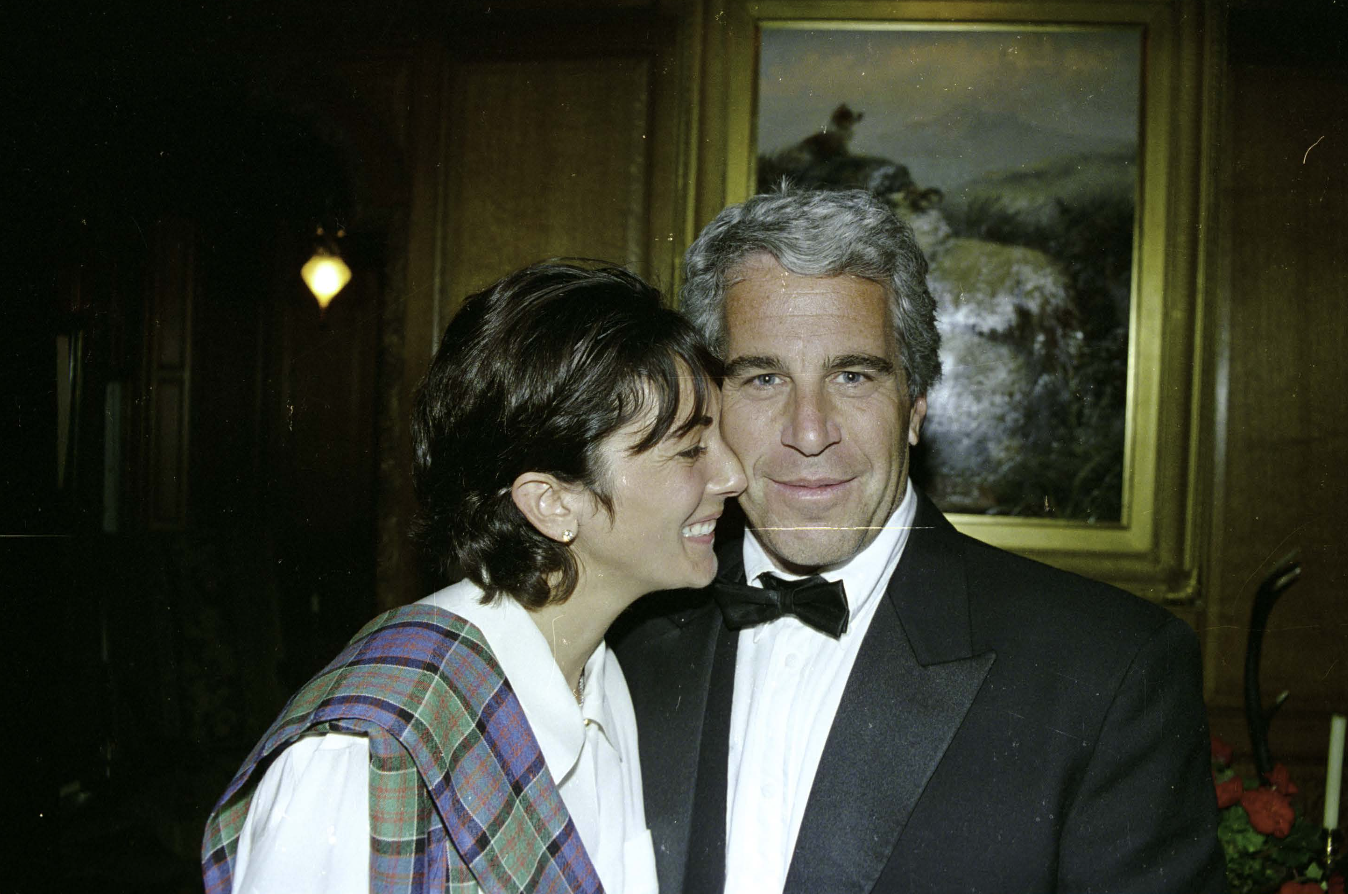

Prince Andrew has consistently denied all the allegations. But a well-circulated picture, which includes Ghislaine Maxwell, apparently shows that the three were – at least on one occasion – in the same place at the same time, though some observers have cast doubt on its veracity. And Giuffre, now 38, has persisted with her lawsuit.

The speed of the trial and the judge’s early decision to exclude some of the evidence Maxwell’s lawyers wanted to bring in her defence suggest that the case was always more clear-cut than many outside the courtroom had expected.

The swift and unanimous verdict also suggests that the jury was more open to believing the 20-year old memories of women from their teenage years than the Maxwell camp had perhaps been prepared for.

It could be argued that the damage to Prince Andrew’s reputation has already been done, including in his Newsnight interview with Emily Maitlis two years ago, when he was asked about his association with Epstein. He already seems persona non grata on royal occasions.

This is the immediate, and narrowly British, aspect of the Maxwell case. But it is just one part of something much broader. Aside from the specific and ingrained depravity exposed during Maxwell’s trial, what emerged was a striking mismatch between the times being described, and now.

Testimony related to the decade between 1994 and 2004, so essentially a generation ago – and to a whole other world of complete impunity for those with the means and the inclination.

Teenage girls, some still legally classed as children, others only just into legal adulthood, were being plucked from the streets or their dysfunctional families, and flown around the world in private planes to private estates for the delectation of rich and powerful men. Plenty of people knew this.

For those involved, it was a parallel normality. It was, in fact, just a more international version of the Hollywood casting couch, which was never unique to Hollywood, or even to the United States (think of the regular goings-on at Cliveden at the time of the Profumo scandal). For those who moved in such circles, there was no price to pay, at least no price that was judicial or moral. Blind eyes were universally turned; that was just what “other people” got up to.

For all the advances of women and women’s rights in the Western world, the 1990s and the early 2000s were still another age. This trial, like the trial that was awaiting Jeffrey Epstein before his suicide, reflects the mores of today; the world of #metoo, a world where a 16 year-old may give legal consent – while also being a victim, or survivor, of exploitation.

Epstein’s experience with the US courts is instructive. Before 2005, he was untroubled by the law, and the law with him. In 2005, the year after the end of the period covered by the Maxwell trial, a complaint from a parent of a 14-year-old girl led to a conviction. But a plea-bargain allowed him to serve only 13 months in prison, with only two cases (of a possible 36) taken into account.

To keep up to speed with all the latest opinions and comment sign up to our free weekly Voices Dispatches newsletter by clicking here

By 2019, when he was arrested again. The crimes were essentially the same, but judged from quite a different perspective. The plea-bargain of a decade before would have been impossible; the reputational damage, even before his suicide, was fatal.

Part of Ghislaine Maxwell’s defence was that she was being tried less for anything she might have done, than for the crimes of the deceased Epstein. There may be a grain of truth here, but it is far from the whole truth.

What is true, and might be more problematic, is that she was tried according to the law and social attitudes of 2021 for actions that took place in quite different times. In terms of child protection and women’s rights, her trial and conviction signify enormous progress.

How far justice is served when social attitudes change so sharply between the time of the crime and its punishment, however, might be another matter.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments