Germany has taken a cautious stance on Russia – and will be on the right side of history

The new three-way German coalition has opted out of the dangerous hysteria about an imminent Russian invasion of Ukraine, writes Mary Dejevsky

Not for the first time, I find myself cheering for Germany – a bit quietly perhaps, not advertising it too much, but cheering nonetheless. This is because Germany – not quite alone, but almost – has opted out of what seems to me to be dangerous hysteria, driven by the United States and the UK, over an imminent Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Germany, without fanfare, has kept its feet on the ground and stood by its national – and, yes, what it doubtless also sees as Europe’s – interests.

I would also venture to remind all those seeking political capital by condemning Germany that the last time it seemed so out of line with US and UK opinion was when Gerhard Schroeder was chancellor and it refused to join in with military action to remove Saddam Hussein. It was right then; and now – as it happens under another Social Democrat chancellor, Olaf Scholz, with another Green foreign minister, Annalena Baerbock – it is right again.

Nor is Germany wrong not to send what the US is euphemistically calling “lethal aid” to Kiev. In declining to join the airlifts of weapons to Ukraine, Germany is not only complying with its own laws (which reflect its own history); it is also, quite rationally, refusing to stoke a long-simmering conflict that could now run out of control. More hardware is not going to make this part of eastern Europe – or anywhere – a safer place.

It hardly needs to be said that Germany’s new three-way coalition – in office only since December – is receiving no thanks for its stance. Inside Germany, the country’s equivalent of our foreign policy grandees are lining up to condemn what they see as Germany’s unwise breach of the supposedly united western front. Abroad, at least in the English-speaking world and Ukraine, Germany is coming in for still more flak, for what is seen as its aversion to conflict (though what is so bad about that I am hard put to say).

One result has been a steady stream of rather injured Germans complaining on social media that their country is once again being hounded and misunderstood. They may be right in one respect. Germany could be more upfront in the English-speaking world about its rationale. Its refusal to wield a big stick does not mean that it also needs to speak quite as softly as it has been doing in the Ukraine crisis so far.

There are reasons for this. The government’s reticence may reflect the fact that it is only just getting used to power, and has to maintain a delicate equilibrium between the three coalition parties – the SPD, the Greens, and the free-market FDP. Doubtless, as a seasoned politician, Scholz also knows that ministers should, if possible, avoid saying or doing anything that would signify a real split in the western alliance. This is where the dismissal of the country’s naval chief comes in.

During a visit to India, Kay-Achim Schoenbach spoke some home truths. He said that talk of a Russian invasion of Ukraine was nonsense, that there was no prospect of Crimea returning to Ukraine, and that Russia just wanted respect – something the west could afford to give. These were, though, unsayable things at this particular juncture, and within hours of his remarks becoming public, he had gone. I would bet, though, that his views remain the same.

Thereafter, perhaps in part to mend some of the perceived damage, Scholz took part in a joint phone call with President Biden and other European leaders, after which they issued a statement of solidarity with Ukraine. Germany also announced the dispatch of 5,000 helmets to Kiev – a contribution for which it received scant thanks, and even ridicule, with people joking that pillows and duvets could come next.

To suggest, however – as many are doing – that Germany’s official stance on the west-Russia standoff over Ukraine is self-indulgent or corrosive to the western alliance, I think, is a mistake. Senior Ukraine government figures have gone so far as to say that the harsh words coming from the US and the UK could be making matters a lot worse. There is much to be said for keeping Russia engaged – indeed, it may be the only way left to fend off a disaster – and Germany, with its Cold War (and more recent) experience of talking to Russia, could be the country to do it.

Germany is also accused of putting its own commercial interests above principles or “values”, by which is meant its commitment to the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline, which was completed last summer and takes gas direct from a terminal near St Petersburg direct to a terminal on Germany’s Baltic coast. The project has been controversial from the start, largely because it bypasses Ukraine, so potentially depriving that country of the transit fees it receives from the current pipeline.

Angela Merkel can also be blamed for weakening Germany’s own energy position by accelerating the planned closure of nuclear power stations, so increasing the country’s dependence on Russian gas – at least until measures designed to reach the net zero climate targets are further advanced.

But the thinking behind Nord Stream 2 does not just reflect Germany’s (entirely reasonable) defence of its own interests; it also reflects a logical and forward-looking approach to relations with Russia. A new pipeline creates a mutual dependency, which necessitates keeping channels of communication open. It also offers benefits to Europe as a whole. How does it possibly make sense, commercially or environmentally, for Europe to despoil its own land or import energy from much further afield (including the US), when it has an abundant source of energy practically on its doorstep?

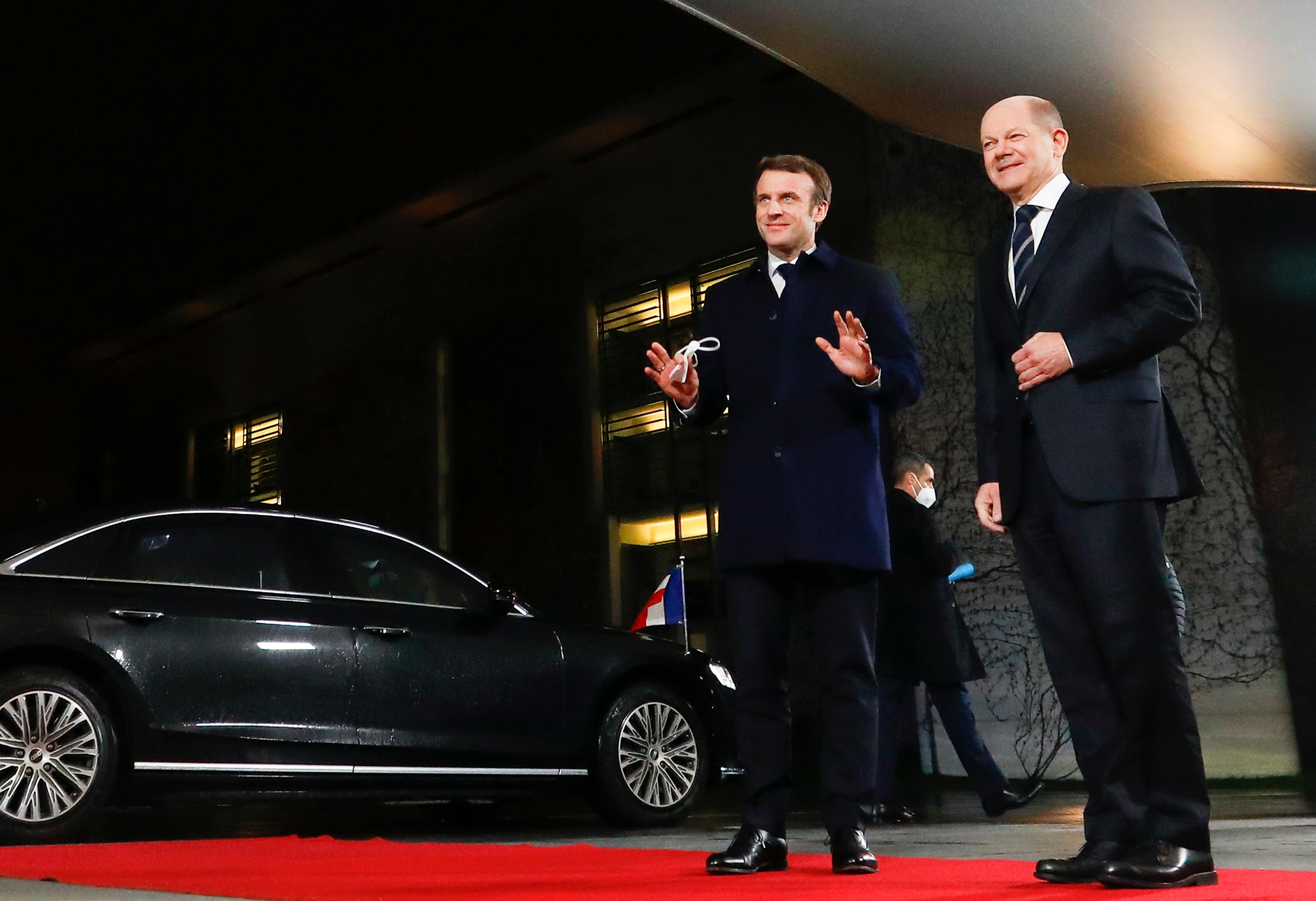

Nor, on the current Ukraine issue, is Germany quite as isolated as it might appear. France has generally kept a low profile, while hinting that its judgement as to the likelihood of a Russian assault on Ukraine does not chime fully with that of the US and the UK. President Macron has moved to revive the so-called Normandy format for talks on the conflict in eastern Ukraine, and has tried to keep links with Moscow alive.

But he may feel he has to tread carefully. While Scholz has just won an election, Macron’s is yet to come, in April, and opposition candidates to his right are snapping at his heels. A misstep on Ukraine – whether in the form of becoming embroiled in a military conflict or standing aside – could prove costly.

In the meantime, the clear lack of enthusiasm in Paris and Berlin for a conflict with Russia is being seen in some quarters as evidence of a lack of resolve, even a split, in the EU. And this, in turn, is seen as why the EU has been largely left out of the loop this time round, even though it was a major player in trying to resolve the Ukraine conflicts of 2014.

To keep up to speed with all the latest opinions and comment sign up to our free weekly Voices newsletter by clicking here

It is too simple, however, to say that the EU is divided on Ukraine. Yes, it is divided on how best to express its support for the country, how far Russia presents a threat to it, and whether it should (ever) join Nato – but not on Ukraine’s status as an independent, sovereign nation.

Until recently, it could be said that the EU’s “hawks” – the former Soviet and eastern bloc states, Sweden and the UK – had a louder or at least an equal voice compared with those more inclined to negotiate with Russia, such as France, Germany and Italy. With Brexit, however, that balance is shifting, and it may shift irrevocably once Scholz is more confident in power, and once Macron – if he does – wins another term as French president.

Biden’s reassurances notwithstanding, US protection does not look as certain as it once did, and the departure of the UK from the EU has lifted a big barrier to the sort of European defence project favoured by Macron. Europe needs to recognise all over again where it sits geographically, sharing a continent with Russia, with the pluses and minuses that brings. Europe is currently at a stage of transition, marked by an open struggle for Ukraine. As with the Iraq war, Germany may yet turn out to be on the right side of history.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments