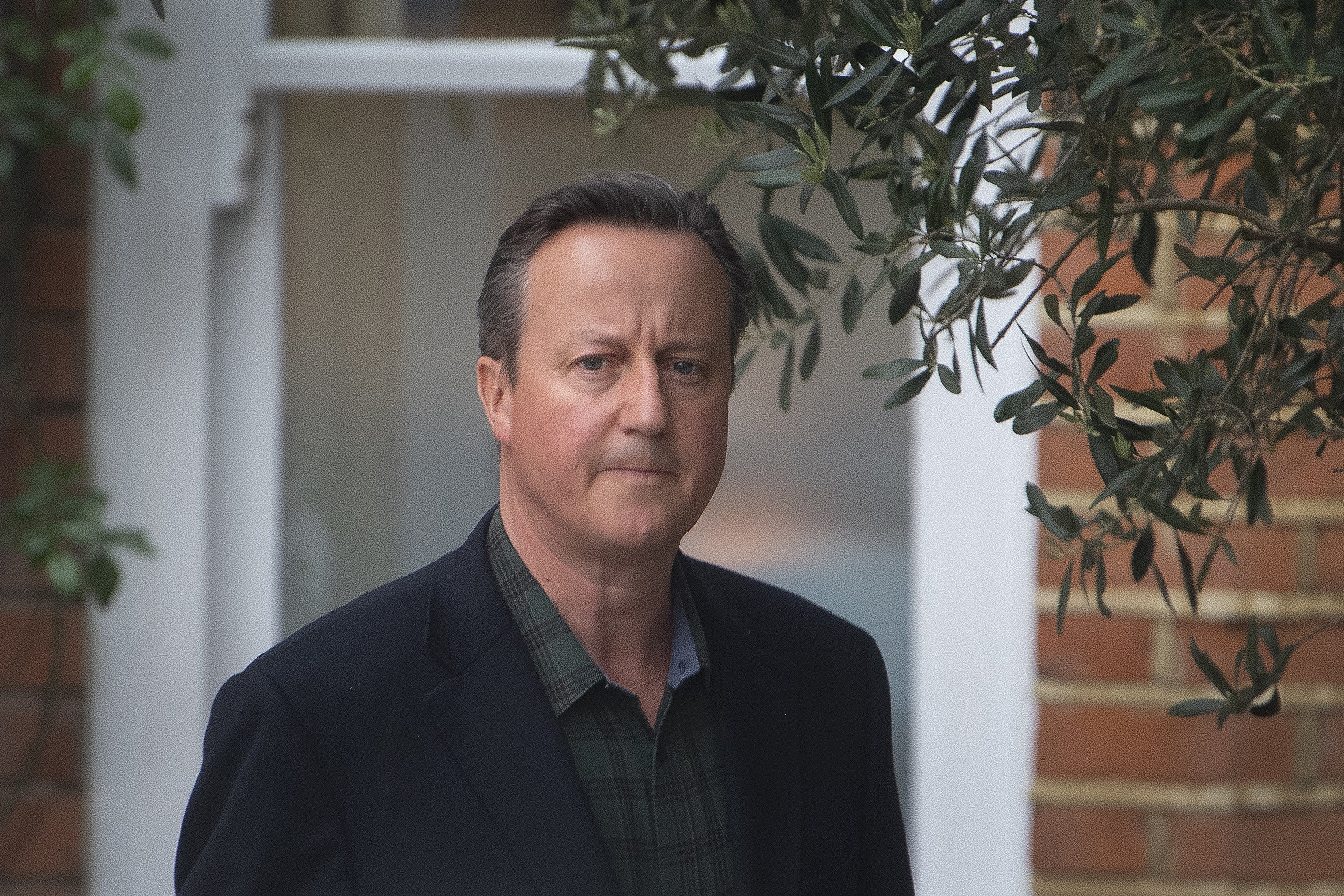

David Cameron has ruined what reputation he had left

The former prime minister was unfairly blamed for Brexit, writes John Rentoul, but cannot escape the embarrassment of the latest headlines

In the history of prime ministerial reputations, David Cameron has taken a surprising lead in the league table of those who have done themselves the most damage since leaving office. “David Cameron did not receive anything like the figures quoted by Panorama,” his spokesperson said yesterday, after the BBC suggested he had made £7m from Greensill before it went bankrupt. But the spokesperson was unwilling to provide the actual figure.

We know that he was paid a salary of £700,000 (it was a million US dollars); that he used the company’s private jet “a handful of times” to commute to his second home in Cornwall; and that he was probably granted shares in the company. If his spokesperson is suggesting that he failed to sell the shares before they became worthless, we would be interested to hear the details.

The precise amount hardly matters. It seems to me that Cameron’s unwillingness to disclose it tells us what we need to know: that it’s embarrassing. It is embarrassing because it was too much, and because it reflects poor judgement on his part. From what I have seen, Greensill’s “products” were nothing special: merely attempts to manage public-sector revenue streams more efficiently in return for skimming off a percentage. Whether they were actually more efficient, no doubt one of the inquiries into the business will be able to tell us. But they weren’t so much in the public interest that it was worth tying a former prime minister’s reputation to them.

For many people, Cameron’s reputation wasn’t worth much anyway. Most prime ministers are remembered for one thing, and his was “losing the EU referendum”. Many of those who wanted Britain to remain in the EU blame him for holding the vote in the first place, which in my view is a misunderstanding of how politics works.

On this question, Cameron had little scope to manage forces beyond his control. If he had not promised a referendum he would have lost the 2015 election, because his party would have become a running brawl and Ukip would have stolen its votes. Even if he had done what some might regard as the principled thing, and given up No 10 to keep us in the EU under an Ed Miliband government, I doubt that it would have put off the inevitable for long. Cameron would have been succeeded by Boris Johnson as Conservative leader, who would have been committed to a referendum on EU membership. It was not unreasonable to try to hold the vote under a prime minister who wanted to stay in.

You don’t get many marks in popular history for trying and failing, though, so he was always bound to be defined by that failure. Even so, he could at least have hoped for some credit in the more considered histories of the early 21st century. He did a great deal to modernise the Conservative brand – much of it by accommodating the New Labour revolution. He legislated for gay marriage; he achieved the 0.7 per cent target for foreign aid; and he seemed to take climate change seriously. Above all, he worked in genuine partnership with the Liberal Democrats. That meant real progress on what Labour began – with wind power, for example – and it meant those on tax credits were protected from the worst of public-spending cuts.

Those cuts still went too fast and too deep, in my opinion, but it wasn’t until after the 2015 election that we saw what a difference the Lib Dems had really made, as Cameron and Osborne started to make big cuts to the welfare budget.

So when it all came to an abrupt end a year later, Cameron had little to show for his time in government in his own right. He could perhaps have claimed, until recently, that some of what was left of his liberal Conservatism hadn’t been reversed by Johnson. But in my opinion, he has now done more to trash his reputation since leaving office than any other prime minister.

Theresa May will get her one line in the history books: “Failed to deliver Brexit.” But she has earned grudging respect for staying in the Commons and arguing for her positions, many of which are at odds with those of her successor. Gordon Brown saved the world from the financial crash and lost an election, but has devoted himself to presbyterian good works since then.

Tony Blair’s is the only recent example of a post-prime-ministerial career that has attracted similar disapproval to Cameron’s, but most of the money Blair has raised has gone to his foundation, employing 200 people who are engaged in development work abroad and policy research at home. And Blair’s interventions in public debate, on Europe and coronavirus, have been worth hearing.

Cameron always regarded Blair as “the master” and tried to learn from him. The pupil has now managed to outdo the teacher, at least in one respect.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments