A warning for people who think the cost of living squeeze will hurt the Tories

Keir Starmer and Rachel Reeves have made progress with the story of a high-tax government squeezing living standards because it is also a low-growth government, writes John Rentoul

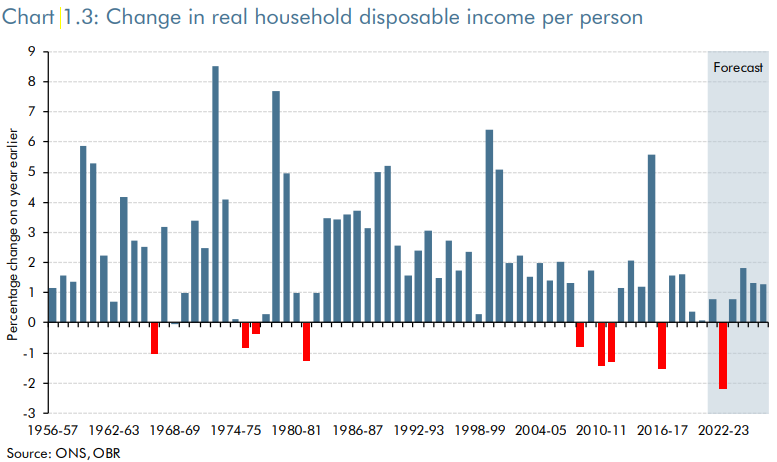

The last time there was a drop in people’s real disposable income was 2016-17. There is a lesson there for politicians: don’t have an election then. There were other reasons Theresa May lost her majority in 2017, but the fall in living standards didn’t help.

There are other lessons. There was a fall in real disposable income in 1980-81. Margaret Thatcher was so unpopular that it was widely assumed she would U-turn on her cruel economic policy, and she wouldn’t last long anyway. The Labour Party took advantage of its obvious winning position to engage in an epic civil war that resulted in the breakaway SDP, which was (less widely) assumed to replace it as the main non-Tory alternative.

It wasn’t the Falklands war that saved Thatcher – although it helped; it was the return to growth. Household incomes rose slightly in 1981-82 and more sharply in 1982-83, just before her landslide election win.

I have been studying chart 1.3 in the Office for Budget Responsibility’s report for the spring statement. It shows the changes in real disposable income every year since 1956-57 up to the forecast for 2026-27. The most striking feature of the chart, much commented on last week, is how deep the cut in 2022-23 is expected to be – hence all those headlines that the chancellor thought were “unhelpful” about the biggest squeeze on living standards since the time of postwar rationing.

One implication of the chart is simple. Now that Boris Johnson has again the power to decide the date of elections, he should not have one next year. Beyond that, however, the implications are harder to read. The portents for the election likely to be in May 2024 are mixed. Thatcher had two years of growth after her 1980-81 dip before her election victory: what is more, her dip was smaller and the bounceback was bigger than Johnson’s is expected to be.

Gordon Brown went to the polls after a dip in 2008-09, followed by a rise in disposable income in 2009-10. Mind you, he did better than expected and the Conservatives were deprived of a majority. But again, Johnson’s dip is deeper and his recovery is predicted to be smaller than Brown’s were.

Hence the intense struggle between rival stories of the cost of living crisis. For Johnson and Rishi Sunak it is all about the cost of locking down the economy for two years, and the international price of natural gas. They haven’t sold this story well, though, and Keir Starmer and Rachel Reeves have made some progress with the story of a high-tax government squeezing living standards because it is also a low-growth government. The economics don’t make much sense, and no one really thinks growth would be magically higher under a Labour government, but there is a kind of political logic to it.

Hence too the unusual significance of next month’s local elections. Starmer launched Labour’s campaign yesterday with a cost of living theme, while the Conservatives are struggling to get the message across about the £150 cut in council tax for bands A to D, designed to help with energy bills, so that they can take the credit for it.

The usual tiresome propaganda about which party gives you lower council tax (Labour because their councils have more lower-band properties or the Conservatives because their councils spend less) has been overlaid by a central government trying to gain some political benefit from a handout few normal people understand. Note also that the Treasury is trying to make payouts to councils for its hardship fund conditional on their saying in their promotional material that the money comes from the national government.

To keep up to speed with all the latest opinions and comment, sign up to our free weekly Voices Dispatches newsletter by clicking here

But the lesson of the Thatcher years is that you can win elections even if a large minority of the electorate is suffering economically. No one thought it was possible for a government to win re-election if more than 1 million people were unemployed – hence the power of the Tories’ “Labour Isn’t Working” poster.

Yet Thatcher managed it in 1983 with unemployment at 4 million. The cut in living standards for state pensioners and people on benefits over the coming year may not be decisive if the state pension and benefits overtake inflation the following year, and if enough other voters are starting to feel better off.

The one thing that the Office for Budget Responsibility’s chart 1.3 does suggest is that Johnson shouldn’t have an election next year. But the year after is a different story. It may be that the result of an election, as Johnson said about exports, “is just will and energy and ambition”.

It may be all about who gets to tell a better story about which way the country is heading.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments