Time to run the NHS at the top of its game, not the top of its capacity

Covid-19 demonstrates that the current approach to NHS efficiency has failed – even on its own terms. It is time to embrace an alternative, says Chris Thomas

“I’ll cut the deficit, not the NHS”. David Cameron’s 2010 election slogan seemed to offer the country the best of both worlds – fiscal responsibility and a strong health service.

Alas, it was too good to be true. Instead, the NHS faced the most brutal decade since its formation. Spending did rise, but far below historic levels, leaving us lagging behind other G7 nations. At the same time, demand increased as our population grew both larger and older. The result was a shortfall, which the NHS was asked to fill by delivering unprecedented efficiency savings.

Whereas once the NHS had been challenged to run at the top of its game, now it was challenged to run at the top of its capacity. Proponents said this would make it sustainable. Covid-19 exposes this as fantasy.

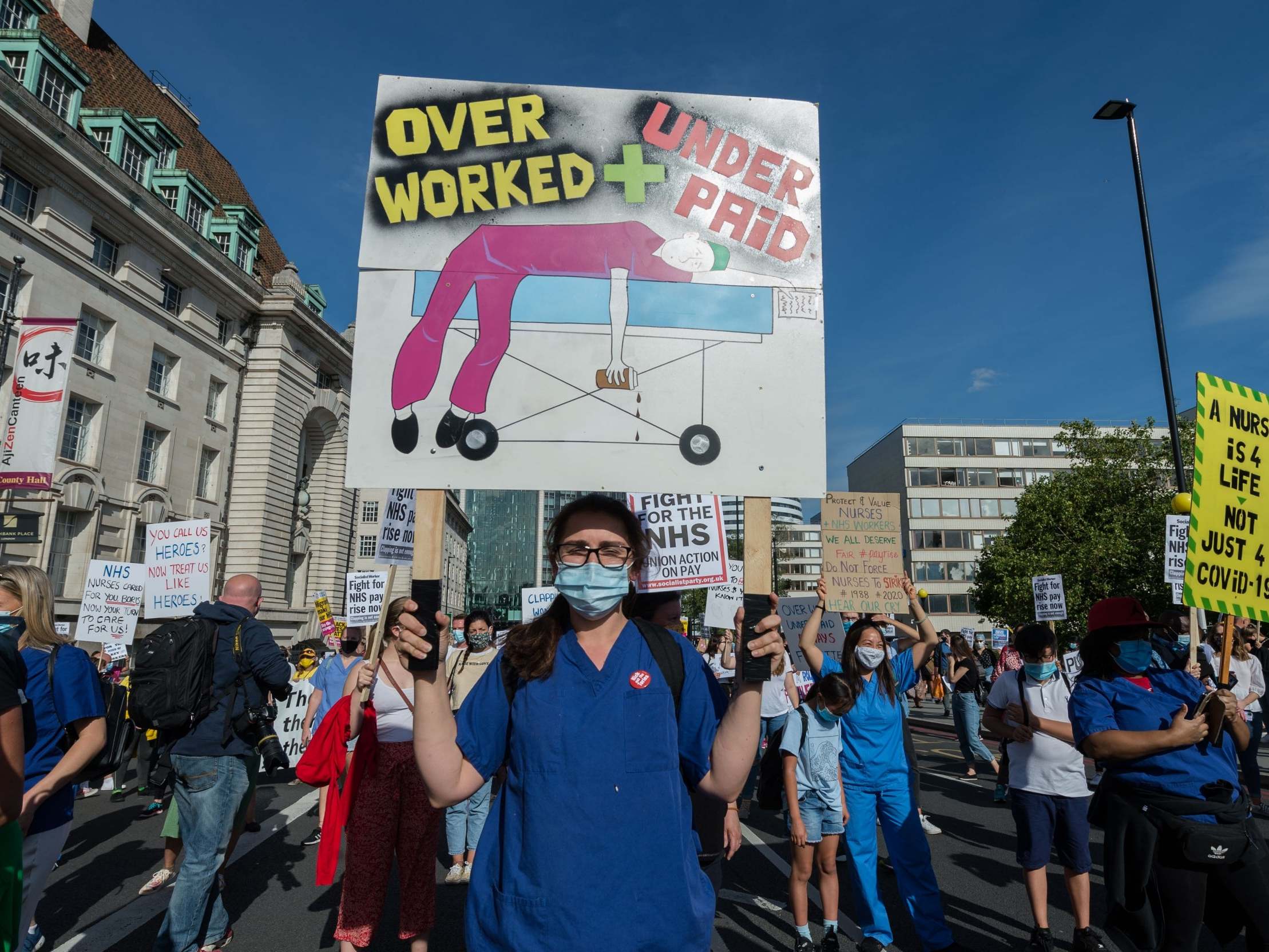

New analysis by the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR) has now revealed just how desperate things had become by the eve of the outbreak. In the NHS, more than four in five hospitals had unsafe occupancy levels. People in those hospitals were being cared for by one of the most highly stretched workforces in the world. The NHS is a big employer, but per person we have fewer doctors and nurses than most other advanced economies.

This fragility wasn’t just confined to hospitals. Social and community care didn’t have the capacity to receive newly discharged patients, while public health and welfare cuts hamstrung the overall health of the nation.

In better times for the nation’s health, ‘running the system hot’ may have looked like a reasonable trade off. But Covid-19 has demonstrated the brutal cost of this operating logic. To prevent the pandemic from overwhelming us, the NHS was forced to cancel 2 million electives; disrupt cancer screening, diagnostics and treatment; and discharge patients en masse to social care.

All as a result of deciding not to invest in spare capacity, because it had been defined as inefficient and stripped out of the system over previous years.

The cost of this lack of resilience has now fallen on the taxpayer. Take the Nightingales. By April, they had already cost £235m. Yet they saw very few patients. They were spare capacity, newly created just in case. But that spare capacity we already had 10 years ago, before 10,000 beds were closed across English hospitals.

Invested just a year earlier, that same funding could have secured almost 1 million nights of hospital care (3,000 more beds over 12 months). Much the same can be said for the other billions extra that the government has had to spend on emergency support for the NHS this year. Invested proactively, it would have eased strain on the system in normal times – and put us in a better place when demand suddenly spiked.

Covid-19 demonstrates that the current approach to NHS efficiency has failed – even on its own terms. It is time to embrace an alternative. Over-simplistic critiques are easy to make. But a lazy focus on single variables – number of beds is the most popular – will not be enough.

Our ambition must be bigger. It should be for a health and care system defined by a race to the top on quality, not to the bottom on funding; where we think of the long term, not just the short term; and where efficiency is about embracing resilience, not settling for fragility.

That might sound too ambitious. Despite the best intentions, politics often loses sight of the big picture, especially during crises. But we can learn from elsewhere.

Take the economy. Since 1997, the government has employed fiscal rules to embed long-term thinking in fiscal policy. After Covid-19, we should embed healthcare resilience rules in much the same way. These should bind government to ensuring capacity in the system; to maintaining a strong and skilled workforce; to excellent levels of public and population health; and to delivering a sustainable level of health and care funding.

Covid-19 is like a natural disaster: it has shown the limits of our current health architecture. After an earthquake, you’d build earthquake-proof housing, and in the same way we must now begin to build crisis-proof healthcare. That means moving away from the failed, narrow efficiency dogma of the past decade, and investing in resilience at the heart of our health and care services.

Chris Thomas is a senior research fellow at the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

2Comments