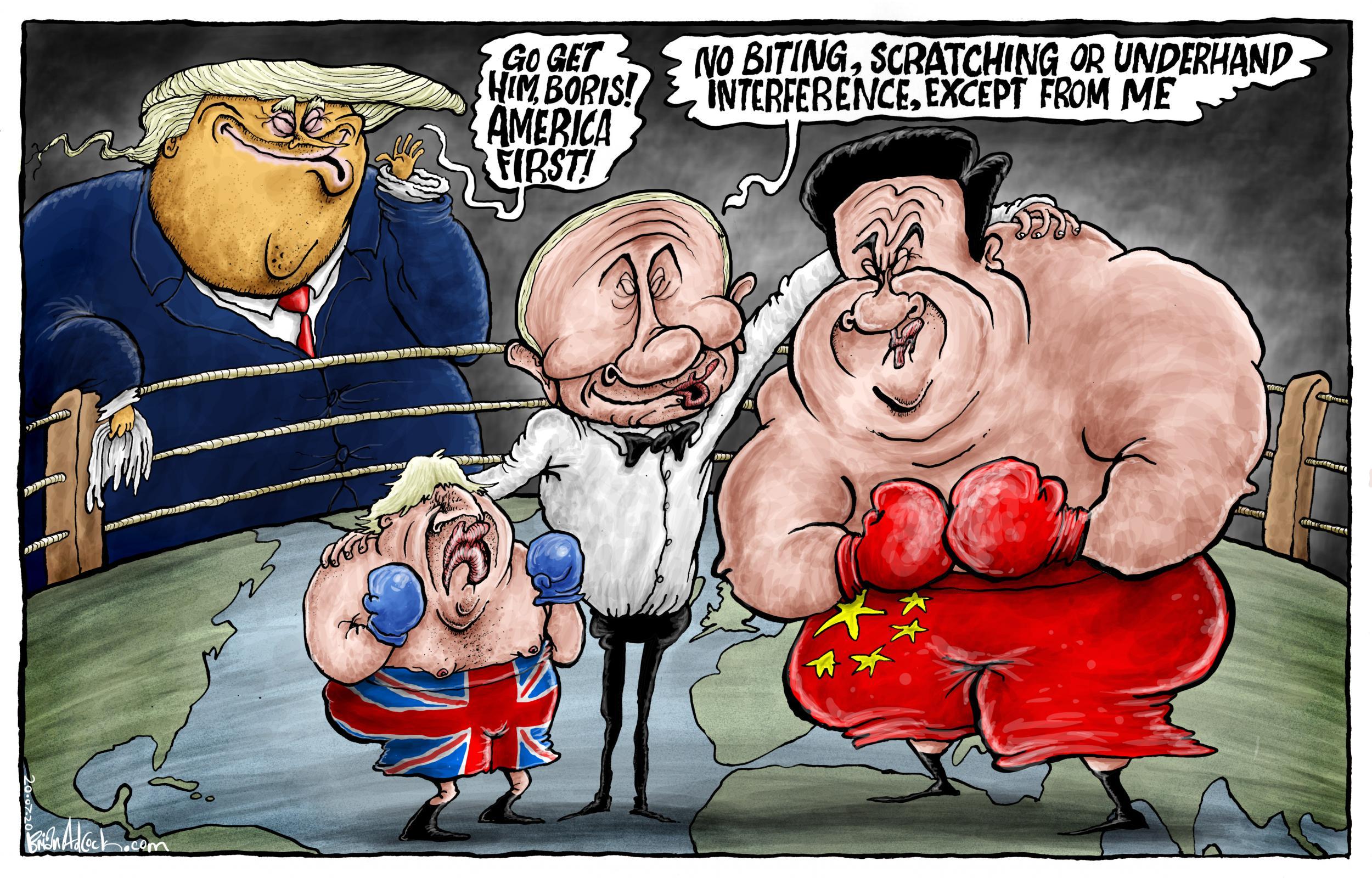

The UK should rethink its hostile relationship with China

Editorial: It is unlikely that the golden era will be revived any time soon, but it should be possible to maintain an adequately open relationship

The relationship between China and the rest of the world becomes more tense almost by the day. From a British perspective, the latest twists include reports that TikTok, the Chinese video-sharing social network, has abandoned its plans to establish a global headquarters in London, and a call on the Andrew Marr show on the BBC from Lisa Nandy, Labour’s shadow foreign secretary, for a stronger response to the treatment of Uighur people in northern China.

Her points were well made but, to be realistic, it is hard to see what pressure the UK can effectively bring on that particular issue. By contrast, the situation in Hong Kong will remain very much a human rights matter, as well as an economic one, and here Britain has a historical responsibility and can exert some leverage. China may feel it no longer needs Hong Kong as an access point to the West’s financial system, but the fact remains that the city has the highest per capita income of China bar the special case of Macau. It remains a beacon of economic progress, a success story that is now threatened by unnecessary political uncertainty.

So the tensions will continue. It would be unrealistic to expect any significant shift in US policy towards China, whoever wins the next presidential election. As China looks like passing the US in terms of economic size about 10 years from now, the rivalry will ramp up. Pressure from the US on its allies to make a choice – us or them – will increase. This will lead to a string of uncomfortable choices, of which the UK decision to cut back the role of Huawei in building its telecommunications infrastructure is but one. For example, Germany may have to choose whether to prioritise its exports of cars to China or to the US. This might seem an obvious decision, for the US is still Germany’s largest export market. But adding imports and exports together, China is its largest trading partner.

The fact that the tensions are not new does not make them any less comfortable.

So what should be done? Some hints of how European nations can maintain a functioning relationship with China came from a video conference last week organised by a think tank called the Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum. The Chinese ambassador, Liu Xiaoming, to the UK pointed out that there were many shared concerns between Europe and China, including climate change, the role of international organisations, and multilateralism. He said that “European politicians” had been making “irresponsible comments” on the new Hong Kong security law – but that was predictable.

“China’s priority is national rejuvenation,” he said. “It is important that China and Europe facilitate each other’s success.” Europe should adopt a different mindset towards China, one which understands that “China’s development creates opportunities rather than challenges”. He left open the door to a continued “golden era” of relations with the UK – which he recalled the British had initiated.

It is unlikely that the golden era will be revived any time soon, but it should be possible to maintain an adequately open relationship. This is difficult under the current leadership in China, which has become notably more assertive since Xi Jinping became president of the People’s Republic in 2013. But leaders change. Policies change. Meanwhile, the role for the UK is to be an orderly, principled and predictable partner – with the emphasis on all three qualities, not one in preference to another.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments