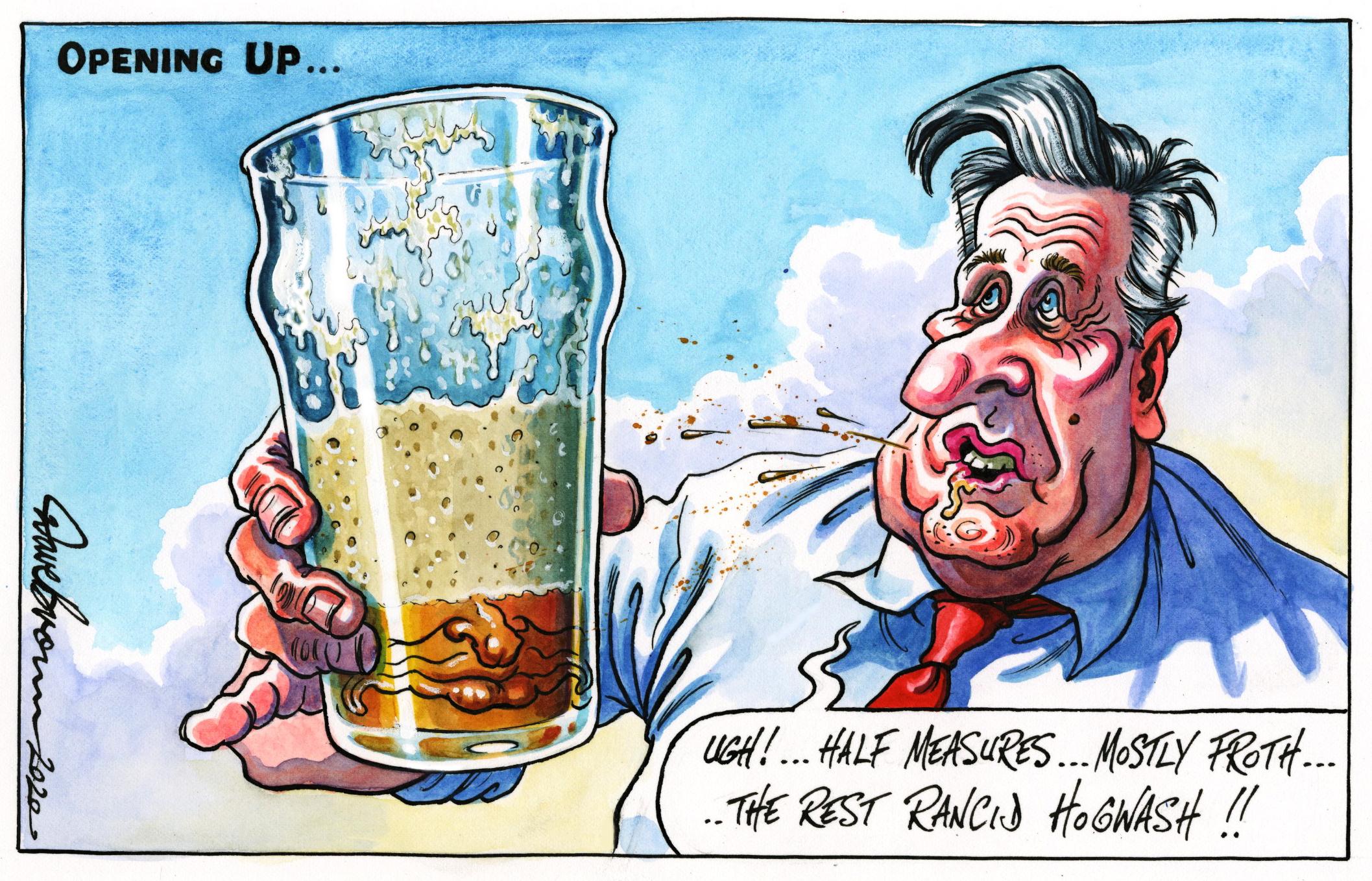

Boris Johnson needs a better plan to protect lives and jobs if a second wave hits the UK

Editorial: Pandemics tend to come in waves and eradication can take years. The prime minister’s weak ideas for fighting new outbreaks are a cause for concern

The joint warning issued by the leaders of the royal medical colleges and the British Medical Association is both sobering and timely. In summary, they caution that the relaxation of lockdown, particularly in England, carries dangers, and their language is clear: “While the future shape of the pandemic in the UK is hard to predict, the available evidence indicates that local flare-ups are increasingly likely and a second wave a real risk.”

Their caution echoes that of the chief medical officer for England, Professor Chris Whitty, who senses problems on the way given the euphoria displayed in some quarters about “Independence Day” on 4 July and a coming disregard for social distancing and face coverings.

Prof Whitty was notably more downbeat than the prime minister: “If people hear a distorted version of what’s being said, that says ‘this is all fine now, it’s gone away’ and start behaving in ways that they normally would have before this virus happened, then, yes, we will get an uptick for sure.” The Sage group seems not to have endorsed the government’s plan, which may also explain why the administrations in Edinburgh, Cardiff and Belfast have not immediately followed suit. The two-metre rule will remain outside of England. Independent experts in public health have voiced even greater concerns.

These medical professionals all have a vested interest, of course, but a legitimate one, because they will find themselves in the front line if a second wave of Covid-19 hits or overwhelms the NHS as summer turns to autumn and then winter, usually a busy time for the health service in any year. Prof Whitty, as with his counterparts in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, also has his reputation and responsibilities to defend.

Historically, as Prof Whitty has said, pandemics tend to come in waves, and eradication can take years. Arguably, another wave is inevitable anyway, given the international nature of the disease, which is surging in America, Brazil, Iran and other places. The under-discussed horror of a constantly mutating virus becoming a permanent fact of life would also mean that a return to actual pre-Covid social relations becomes impossible. Nature may prevail over human science.

Everyone would feel much more confident if the test and trace system was more effective, because that is the main line of defence if infection numbers increase. Although some notable, long overdue, progress has been made in recent weeks, there remain disturbing problems. As Sir Keir Starmer points out, one third of those identified as Covid-19 positive in a test have not been contacted, for whatever reason, and therefore neither have other members of their households, friends and fellow workers. With a virus easily transmitted and a high R number that is a considerable cause for concern.

Sir Keir was also right to raise the predicament faced by local authorities. Even if they have the resources to undertake what Boris Johnson terms “cluster busting” on local outbreaks, they lack the guidance and powers to order local lockdowns. Local resilience forums and public health departments are all very well, but who orders the police under what legislation to patrol a lockdown, order people indoors and close down premises?

Mr Johnson says he will not hesitate to reinstate local or even national lockdowns if necessary. Fine, but he should also be aware of the renewed economic damage that will inflict. The economic “recovery plan” will lie in ruins. He must also know full well the further political damage a second lockdown would inflict on him. Maybe he’s calculated that, politically, as things stand he doesn’t have that much to lose from a bit of a gamble. But it involves gambling with other people’s jobs and other people’s lives.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments